t is almost impossible to read the news without coming across a lead story cataloguing the latest cyber breach or misuse of data. Intellectual property is being stolen from companies at an alarming rate. Foreign actors are meddling in elections through fake social media accounts, along with other more nefarious means — including the surreptitious access of internal campaign emails. Criminals use the dark recesses of the internet to sell drugs, guns and even people. And terrorist groups use digital media to recruit and inspire prospective adherents the world over.

This is not even the worst of it. Whether one views Edward Snowden as a hero or a traitor, the fact is that the information he revealed regarding the extent of governmental surveillance and the close relationship between traditionally distinct public and private entities has damaged systemic trust in a profound way. On top of this more robust surveillance state, countries are creating advanced cyber weapons capable of devastating real-world effects. At the same time, more and more critical infrastructure is being digitally enabled and is also, therefore, capable of being digitally disabled by bad actors.

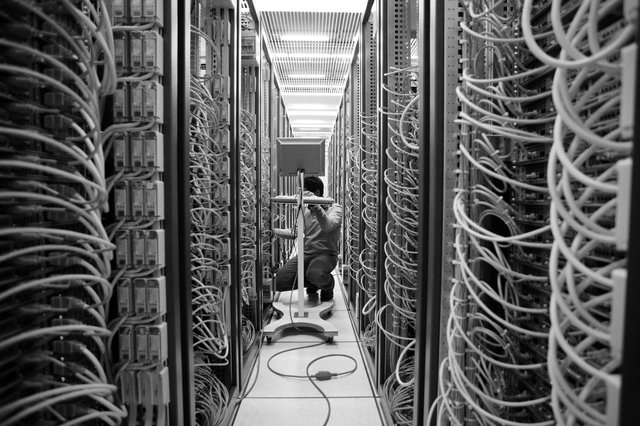

The number of companies and governments that have fallen prey to digital hacking are almost too numerous to count — Ashley Madison, the Bank of Montreal, CIBC, eBay, Equifax and JP Morgan Chase offer ready examples. The volume of these events lays bare the paradox of the digital economy and cyber security. On the one hand, technology has led to convenience, efficiency and wealth creation — and so, companies push to connect everything that can be connected. On the other hand, this great push to digitize society has meant building inherent vulnerability into the core of the economic model. This is all taking place atop a deeply fragmented and underdeveloped system of global rules.

This great push to digitize society has meant building inherent vulnerability into the core of the economic model.

Given this paradox, the purpose behind this essay series on security in cyberspace is threefold. First, it brings together an interdisciplinary team, including the private sector, academics and leading experts to provide creative ideas and fresh thinking in these emergent areas surrounding data governance, cyber security and new technology. Second, it aims to advance a public policy debate that recognizes that while cyber security threats are increasing in both number and sophistication, there is economic potential for Canadian firms to capitalize on a growing market. Third, it argues for the advancement of a more stable international institutional order. The international rules-based system in cyberspace is still in its infancy, and innovative thinking is needed to make sure that Canada can play a leadership role in crafting the governance architecture.

The National Cyber Security Strategy released in June 2018 marks an important step forward for Canada in the cyber domain — but there is much left to do. The strategy advances Canadian interests in a number of ways. For example, it recognizes that “cyber security is the companion to innovation and the protector of prosperity” and cyber security is now an essential element to a functioning innovation economy (Public Safety Canada 2018).

The Government of Canada’s efforts in this area are set out in three themes:

- security and resilience (to enhance cyber security capabilities to better protect Canadians and defend critical government and private sector systems);

- cyber innovation (to position Canada as a global leader in cyber security); and

- leadership and collaboration (to have the federal government act as a leadership point in Canada and work to shape the international cyber security environment in Canada’s favour).

Given this national and international context, this essay series takes a broad view of cyber security and addresses a range of topics, from the governance of emerging technology, including artificial intelligence and quantum computers, to the dark Web and cyber weapons. The unifying question underlying this effort is: how can we build a system of governance that enhances global systemic trust and creates opportunities for “middle” power countries such as Canada to advance their strategic and economic interests through enhanced governance arrangements? Cyberspace presents both threats and opportunities — at the same time — and the collective challenge is to advance policy that can best maximize the opportunities while mitigating the threats in a constantly changing global environment.

While, at first glance, the themes set out in the National Cyber Security Strategy seem categorically discrete, if implemented properly in a way that also accounts for the value of data in the new intangible (or data-driven) economy, they can be mutually reinforcing. The data-driven economy is an unprecedented economic and societal force that is revolutionizing nearly every industry and leading to new power dynamics between countries. As such, these thematic areas highlight a dynamic interplay between domestic and foreign (or global) policy goals.

Enhancing cyber security readiness and network resilience in both government and private sector systems makes it more difficult for adversaries, both foreign and domestic, to exploit Canadian systems. This, in turn, enhances trust in the digital ecosystem in Canada, because it makes it less likely that personal, financial or corporate information will be compromised by security breaches or unscrupulous data practices. By establishing greater domestic cyber security readiness and resilience, it also makes it a much more credible effort for Canada to try and position itself as a global leader in the field.

On the theme of cyber innovation, the unfortunate fact is that the cyber security industry is growing, based on necessity. This creates both an economic imperative and an opportunity. According to the recent Canadian Survey of Cyber Security and Cybercrime, conducted by Statistics Canada, Canadian businesses are spending approximately $14 billion on cyber security per year.1 At the same time, various estimates present staggering figures representing the loss to the Canadian economy because of cyber crime and espionage.2 In this way, the cyber security industry contributes significantly to Canada’s economy, while cyber criminals and foreign adversaries act like a parasite on that value. Moreover, while the growth projections vary, it seems clear that the industry and the economic opportunities created for Canadian companies will continue to grow along with the threat. It will be important to advance domestic policy that allows the best Canadian firms to grow at home, but also to reach international markets.

It will be equally imperative that Canada push to advance global rules or norms in cyber space that foster greater stability. This is particularly important because a lack of clear rules or norms contributes — at least in some way — to a permissive environment where adversarial actors take advantage of the ambiguity in the rules to launch offensive cyber operations against both Canadian business and governmental actors.

On the theme of global rules, there are a number of important observations reflected in Canada’s defence policy. First, that the “most sophisticated cyber threats come from the intelligence and military services of foreign states” (National Defence 2017, 56). Second, that it is the technologically advanced governments and private businesses that are the most vulnerable to state-sponsored cyber espionage and other forms of cyber aggression. Third, that the threat from these forms of state-sponsored cyber aggression will likely continue for the foreseeable future. Finally, that addressing “the threat is complicated by the difficulties involved in identifying the source of cyber attacks with certainty and the jurisdictional challenges caused by the possible remoteness of cyber attacks” (ibid.).

This has led to a deeply contested operational environment in cyber space. According to Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy:

State and non-state actors are increasingly pursuing their agendas using hybrid methods in the “grey zone” that exists just below the threshold of armed conflict. Hybrid methods involve the coordinated application of diplomatic, informational, cyber, military and economic instruments to achieve strategic or operational objectives. They often rely on the deliberate spread of misinformation to sow confusion and discord in the international community, create ambiguity and maintain deniability. The use of hybrid methods increases the potential for misperception and miscalculation. Hybrid methods are frequently used to undermine the credibility and legitimacy of a national government or international alliance. By staying in the fog of the grey zone, states can influence events in their favour without triggering outright armed conflict. The use of hybrid methods presents challenges in terms of detection, attribution and response for Canada and its allies, including the understanding and application of NATO’s Article 5. (ibid., 53)

The ability of foreign adversaries to operate in this grey zone is possible because there is no universally understood set of norms that apply in cyber space. Rather, actors stretch to interpret existing legal rules, such as the United Nations Charter and international humanitarian law, as applicable to technologies and actions that could not have been contemplated at the time that the law was written.

This trend is worrying, although it is not surprising because it is simply a digital continuation of geopolitical rivalry. David Vigneault, director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, recently remarked that “economic espionage represents a long-term threat to Canada’s economy and to our prosperity” (Vigneault 2018). He based this assessment on “a trend of state-sponsored espionage in fields that are crucial to Canada’s ability to build and sustain a prosperous, knowledge-based economy [including] areas such as A.I., quantum technology, 5G, biopharma, and clean tech” (ibid.). Owing to the highly sophisticated nature of these efforts, the reality is that adversarial nations are targeting “the foundation of Canada’s future economic growth” (ibid.).

This is all leading to a crisis in trust at the individual level, with individuals feeling vulnerable online. In 2018, CIGI conducted a Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust in partnership with Ipsos, a global market research and a consulting firm. The firm surveyed internet users in 25 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hong Kong (China), India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, South Africa, the Republic of Korea, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey and the United States. The results were telling: over half of internet users surveyed around the world are more concerned about their online privacy than they were a year ago, reflecting growing concern around the world about online privacy (CIGI and Ipsos 2018).

Clearly there is a deep geopolitical rivalry at play that will come to define the distribution of both wealth and power in the future.

Even more dangerous is the breakdown in trust between states. Perhaps there is no clearer Canadian example than recent events surrounding China-based company Huawei, and the discussions related to banning the company from Canada’s 5G networks. 5G is the term used to represent the fifth-generation cellular mobile communications, succeeding LTE. It will be the backbone of the digital economy and lay the foundation for mobile computing, smart sensors, advanced automation and the Internet of Things — including connected cars. In fact, the issue has become so politically charged that two members of the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Republican Senator Marco Rubio and Democrat Senator Mark Warner, wrote to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau urging him to ban Huawei from Canada’s mobile network. The two senators wrote: “We are concerned about the impact that any decision to include Huawei in Canada’s 5G networks will have on both Canadian national security and ‘Five Eyes’ joint intelligence cooperation among the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada” (Warner and Rubio 2018).

Clearly there is a deep geopolitical rivalry at play that will come to define the distribution of both wealth and power in the future. This has led to the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, an effort that Canada — along with 65 other states — supports. This broad call for trust is an effort to get states to agree to a set of international rules for cyberspace. However, it falls well short of a detailed treaty. Rather, it is a very high level non-binding document that, at its highest, is a call for states to “promote the widespread acceptance and implementation of international norms of responsible behavior as well as confidence-building measures in cyberspace” (France Diplomatie 2018, 3).

Works Cited

CIGI and Ipsos. 2018. “2018 CIGI-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust.” www.cigionline.org/internet-survey-2018.

France Diplomatie. 2018. “Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace.” November 12. www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/paris_call_cyber_cle443433-1.pdf.

National Defence. 2017. Strong Secure Engaged: Canada's Defence Policy. Government of Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/mdn-dnd/D2-386-2017-eng.pdf.

Public Safety Canada. 2018. National Cyber Security Strategy. Government of Canada. www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ntnl-cbr-scrt-strtg/ntnl-cbr-scrt-strtg-en.pdf.

Vigneault, David. 2018. “Remarks by Director David Vigneault at the Economic Club of Canada.” Canadian Security Intelligence Service speech, December 4. www.canada.ca/en/security-intelligence-service/news/2018/12/remarks-by-director-david-vigneault-at-the-economic-club-of-canada.html.

Warner, Mark R. and Marco Rubio. 2018. “Warner and Rubio Urge PM Trudeau to Reconsider Huawei Inclusion in Canada’s 5G Network.” Press release, October 12. www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2018/10/warner-rubio-urge-pm-trudeau-to-reconsider-huawei-inclusion-in-canada-s-5g-network.

The opinions expressed in this article/multimedia are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIGI or its Board of Directors.