According to Thai legend, albino elephants were regarded as holy. If a Thai king became dissatisfied with a subordinate, the king would give him the “gift” of a white elephant. Keeping a white elephant was very expensive and, in most cases, would ruin its owner, as they would have to provide special food for the elephant as well as access for people to worship it. It may be that the development issue has a similar dimension for the G20. Does the positive value added by consideration of the development issue outweigh the burden? Is development a linchpin of the G20 agenda, since sustainable growth and prosperity in this interconnected world is dependent on the experience of developing and emerging countries? Or, is the development area a Potemkin village of intransigent issues?

This article reviews how development was treated at the last three G20 summits and then explores the wisdom of keeping global development on the G20 agenda rather than having it "mainstreamed" across the G20’s core work.

In general, the G20 adds an issue to its agenda if there is a vexing problem with major implications for all its members that is unlikely to be resolved elsewhere. The G20 role should be clear, with prospects for strengthening other international institutions and for a probable positive outcome that would enhance G20 credibility. Applying these criteria, does development merit a place on the G20 agenda?

The G20 has several types of initiatives or “tools” at its disposal. It can simply pronounce its view or commit to act domestically. Since G20 communiqués are widely publicized, they are able to focus attention on an issue and may influence events. The G20 shapes the future research agenda, framing terms of reference and inviting groups of G20 ministers or international organizations to prepare a report for consideration at a future G20 meeting. It can mobilize resources as it did at the 2009 London summit to deal with the financial crisis. The G20 can create a new institution — witness the Financial Stability Board. What is the prospect for any of these “tools” to be applied to global development issues?

Development on the G20 Agenda?

Should development be on the G20 agenda? While global development and poverty is of concern to all G20 members, and the existing body of international institutions could be criticized for ineffective results, the issue is whether the G20 would be able to do better. Is there a set of potentially successful G20 initiatives that would add to its credibility? Based on this criterion, it appears that development should not be on the G20 agenda. Why, then, did Korea put development on the G20 agenda? Why did France and Mexico follow up to include it in their presidencies? Why is Russia keeping it on the agenda?

The G20 presidency has the significant prerogative to add an issue to the summit agenda. There are different explanations for the Korean decision in 2010. Perhaps the Koreans — keen for the G20 to succeed — were responding to the need to ensure the sustained legitimacy of the G20 and to build a medium-term role for it beyond that of a crisis control centre (Schulz, 2011). Citing the growing interdependencies among countries, possibly the Koreans put development on the agenda to demonstrate a concern with the economic performance of non-G20 members. The Koreans felt they could provide value added to the development discourse, based on their remarkable historical performance, emphasizing growth and infrastructure development. The objective was, perhaps, to move global development discussions beyond the aid focus and make self-sustaining growth based on progressive capacity development the key feature. Additionally, France and Mexico supported the idea, increasing the potential for the success of Korea’s initiative. [1]

The “Seoul Development Consensus for Shared Growth”[2] was characterized as a departure from the discredited “Washington Consensus.”[3] The Seoul Development Consensus allows a role for state intervention; it presumes that solutions should be tailored to the requirements of individual countries, with developing countries taking the lead in designing packages of reforms and policies best suited to their needs. It has six core principles: focus on economic growth; global development partnership; global or regional systemic issues; private sector participation; complementarity; and outcome orientation. The principles are all uncontroversial — except perhaps for some grumbling about being business-friendly. There are nine “pillars” — the key ingredients of self-sustaining growth: infrastructure; private investment and job creation; human resource development; trade; financial inclusion; resilient growth; food security; domestic resource mobilization; and knowledge sharing.

The priorities of the French presidency in 2011 were: restoring economic confidence in the euro zone; the international monetary system; the social agenda; financial regulation; and the development agenda. While acknowledging progress under the nine Seoul pillars, development priorities at Cannes were: food security; infrastructure; and the financing of development. The French have always had a special interest in innovative financing. Concerning development financing, President Sarkozy asked Bill Gates to submit proposals to the heads of state and government at Cannes. The Gates report was to include a “menu of options” for innovative financing mechanisms of which G20 members would be invited to choose at least one for implementation. [4] A separate briefing on France’s priorities for their G20 meeting highlights included “Development, with a particular focus on food price volatility and Africa.” and “Fighting corruption, including promoting transparency in extractive industry revenues.” [5]

The performance at Cannes was deemed unsuccessful for failing to come up with a new development story concerning the links between economic growth and social objectives:

“The G20 development agenda has had so far limited added value to ongoing global development processes. It lacks both institutional strength and a convincing narrative. Moreover, short-lived celebrity initiatives, such as the financing report submitted by Bill Gates, cannot distract from the weak performance of the G20 as a development driver” (Schulz, 2011).

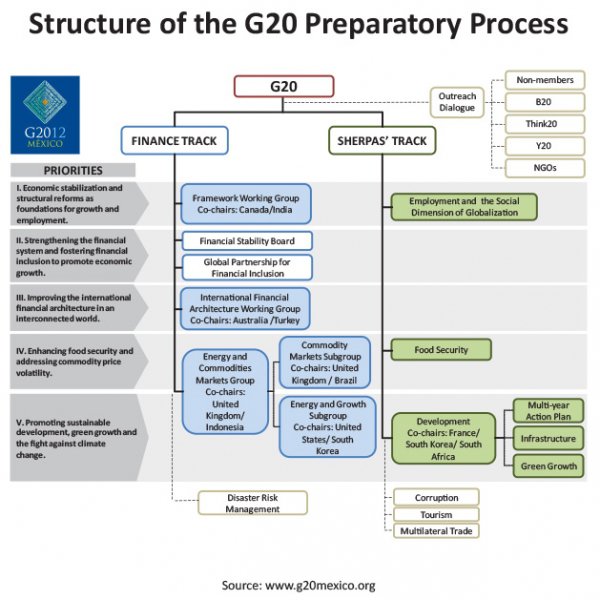

The Mexicans retained a focus on development during their 2012 presidency. Their approach was to follow up the pillars in the “Multi-Year Action Plan on Development” with an emphasis on infrastructure and green growth. Mexico introduced a more structured approach to preparation with two “tracks” (see chart below). “The Sherpas’ track focuses on political, non-financial issues, such as: employment, agriculture, energy, the fight against corruption and development, among others.” (G2012 México, 2012: 5; and G2012 México, 2012a). This two-track approach is problematic — it depreciates the impact of the Sherpas’ track. Most of the potential action options in the development area require the expertise and assent of the “Finance track.”

The Russian 2013 presidency focus is on four of the nine pillars — food security, financial inclusion, human resource development and infrastructure. In each of these four priority areas, there are constraints on the work of the Development Working Group (DWG) — the relevant policy areas are outside its sphere of influence. For example, in the food security area, regulation of commodity futures markets, the reduction of agricultural subsidies and biofuel mandates are outside the DWG’s purview. For financial inclusion, regulation or promotion of micro finance is outside its mandate. For human resource development, authority for subsidies and tax incentives belong to the finance ministry. In the infrastructure area, the effective instruments are all financial, for example, local currency bond markets, role of sovereign wealth funds and increased multilateral development bank lending. On balance, the DWG is seemingly restricted to being a harmless discussion forum attempting to reach a common understanding about good practices.

The G20’s Tools

The G20 has the power to shape the global discourse — its pronouncements are reported widely. But in the development area, the G20 is a secondary player — it has significant competition in shaping the global discussion. The president of the World Bank is pushing the eradication of poverty by 2030. The United Nations will monopolize the debate for the next 18 months discussing the Rio+20 sustainability goals and the post-2015 successor to the UN Millennium Development Goals.

The G20 can influence the future research agenda, posing specific questions and issuing remits to be reported on at future G20 meetings. But, in the development area, the G20 faces a crowded field. Its reputation is handicapped by the poor performance on its request for a report on fossil fuel subsidies, where commitments to a first class product did not result in implementation. International organizations will be reluctant to divert resources to respond to the G20 if they see little prospect for action.

The G20 can commit to finding the resources for a global problem. At the 2009 London summit, it committed to mobilizing resources to deal with the financial crisis and for the International Monetary Fund. But in the financing for development area, the G20 appears impotent. The G20 discourse on financing is not, however, limited to resources for development. The G20 “Study Group on Climate Financing” issued an insignificant report of little value. [6] The jury is out on whether the G20 can make a meaningful contribution to mobilizing domestic resources or even on addressing illicit capital flight.

The G20 is able to create a new institution to fill a gap in the global governance architecture for development, as they did with the Financial Stability Board. In the development area, the issue is not gaps in governance. It is difficult to argue that a gap exists for development. There are, perhaps, too many development organizations – the multilateral development banks, United Nations agencies, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee, the national aid and international cooperation ministries and countless non-governmental organizations and funds. The organizations and agencies lack coherence, but none of these actors will accept an overall executive institution. In theory, the G20 could be the executive institution to ensure coherence in decision making and financing, but the G20 members have very different approaches to development and no actual resources available to initiate pilot or demonstration projects.

Conclusion

One easy option for the Russian presidency to minimize expectations is to report on past commitments and then request ideas on new institutional arrangements with respect to food security and financial inclusion, which would be reported at future summits. A more ambitious alternative would be to recall the September 2011 statement of the G20 meeting on development with the ministers of finance and the ministers responsible for development cooperation:

“The G20 development agenda is central to the issues facing the G20. Development issues and global economic issues can no longer be treated in isolation…At a time when economic uncertainties regarding world growth are on the rise, and global imbalances must be eliminated, economic growth can contribute to global economic recovery by creating new focal points of growth and helping to reduce disparities” (G20 DWG, 2011).

Development ministers are not responsible for the substantive policy prescriptions that enable development — all the policy tools are found in other ministries. Trade access, infrastructure, agricultural development, tax policy, funding for education and human resources development, policies on commodity and food price volatility, and anti-corruption, are all policy instruments wielded by other ministers. The role of the G20 and the potential contribution of the G20 DWG would be to highlight the crosscutting dimensions of the various other policies and their impact on development. G20 development ministers and the DWG must be “pests” and “interfere” in the other G20 working groups, championing development interests and promoting ideas that shape other policies with full consideration of their importance for developing countries.

The Russian presidency this year, and the Australians in 2014, have a choice. They can assess development as a white elephant, build a Potemkin village and try to avoid the complexities by “mainstreaming” development on the G20 agenda. Or, they can agree with the September 2011 G20 statement that “development issues and global economic issues can no longer be treated in isolation.” To ensure that future G20 decisions will not trivialize development, the DWG assessment of the impact of all G20 policies would become an integral input in all tracks of the G20 process. Joint meetings of ministers of finance and the ministers responsible for development cooperation would become a keystone of the G20 process.

Works Cited:

G20 DWG (2011). “Preliminary Report on the G20 Action Plan on Development: Summary by the French Presidency.” September 23. Available at: www.g20.utoronto.ca/2011/2011-dev-plan-110923-en.html.

G2012 México (2012). Mexico’s Presidency of the G-20. Discussion paper, January. Available at: www.g20mexico.org/images/pdfs/diseng.pdf.

G2012 México (2012a). “Sherpa’s Track.” Available at: www.g20mexico.org/en/sherps-track.

Schulz, Nils-Sjard (2011). The G20 — Driving development behind closed doors. FRIDE Policy Brief no. 107, December. Madrid. Available at: www.fride.org/download/PB_107_G20_development.pdf

Endnotes: