The decades-long dispute between Ecuadorian Indigenous communities, Chevron and the government of Ecuador may seem to many as the nadir of justice delayed and justice denied, but natural resource-related friction between extractive sector industries, Indigenous communities and governments is commonplace around the world. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was drafted against this backdrop, in which Indigenous peoples who had suffered dispossession of lands, territories and resources under colonization were seeking recognition of their inherent human rights and, in particular, their right to self-determination. UNDRIP declares that the world’s Indigenous peoples have the right to control developments affecting them and their lands, territories and resources, to enable them to maintain and strengthen their institutions, cultures and traditions. Implementation of UNDRIP provides important international guidance for addressing these points of friction.

For decades, Phil Fontaine, a three-term national chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), has worked to obtain redress and apologies for Indigenous children sent to residential schools, to establish the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and for the economic empowerment of Indigenous communities. Born in Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba, where he served as chief in early adulthood, Fontaine is a long-time advocate for Indigenous communities engaging with corporations interested in extractive and other industrial projects in traditional lands. He has been both criticized and praised for this work.

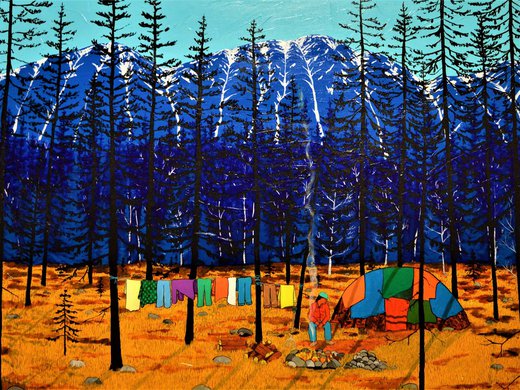

In this article, Oonagh Fitzgerald, director of CIGI’s International Law Research Program, talks with Phil Fontaine about his history of representing Indigenous peoples in Canada, the importance of collaborative, inclusive approaches to resource development, and his vision for the conference “Indigenous Solutions for Environmental Challenges” in Banff, Alberta.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

OF: I’m very grateful that you can join us today, Phil. You have an impressive biography — what are some of the other important milestones in your career of representing Indigenous peoples in Canada?

PF: Of course, during my tenure as national chief of the AFN, I saw the residential school settlement, the apology of June 11, 2008, and the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I travelled to the Vatican for a private audience with Pope Benedict XVI to talk about the residential school experience and our desire to have a clear expression of remorse on the part of the Catholic Church. It’s also important to note that before I became national chief I was chief in my own community, and there were a number of milestones there as well. We were the first community in Canada to take over local control of Indian education in our community, meaning we could hire (and fire) our teachers. We established the first on-reserve welfare agency and treatment centre. When we talk about my involvement in Indigenous politics and the representation of First Nations people in Canada, I’m very proud of those moments, too.

OF: In more recent years, after the truth and reconciliation process was launched, it seems that you’ve been really focusing on the goal of Indigenous communities engaging with corporations to get a better deal out of resource development projects. It would be interesting to hear your thoughts on reconciliation, especially in the context of settler communities and corporations wanting to do business in traditional lands.

PF: When we talk about reconciliation we’re talking about new relationships. But we can’t transform these relationships without first dealing with the old relationships. In the case of resource companies, the courts have been very clear about their obligations to Indigenous communities that may be sitting on some very valuable resource, whether it’s oil, gas, a pipeline route, forestry, mining or any other resource. There are important obligations that have become part of doing business with Indigenous peoples. This is echoed in the UNDRIP as well. Among other things, the Declaration speaks about the right of Indigenous peoples to freely give or withhold prior and informed consent. Today, Indigenous peoples are much more informed and engaged, so resource companies can’t simply ignore that. The language used now by Indigenous peoples has changed fundamentally as they seek to implement the idea of free, prior and informed consent in their communities.

OF: Does UNDRIP provide Indigenous communities with the language to be more assertive about their rights, and to be better informed?

PF: In the old days we never spoke about partnerships, joint ventures or equity ownership. But now, that is the language spoken in Indigenous communities, especially those that sit on something of great value to resource companies.

OF: I understand that the long-running Ecuadorian environmental case, Aguinda v. Chevron, may have provided some impetus for this conference to consider the role of courts in resolving disputes involving resource sector industries and Indigenous peoples in Canada and around the world, but I gather your vision for the conference and its themes are much broader.

PF: The conference isn’t about indiscriminately attacking resource companies, and it isn’t just about the Aguinda v. Chevron case. It’s about ensuring that the people that are on either side of the equation — whether they are for resource development or oppose it — engage in a respectful dialogue. Hopefully, through these conversations, we will be able to establish something that is workable for everyone impacted.

It’s really all about conversation. And that’s what reconciliation is about as well. It’s about talking, and making sure that people have an opportunity to learn from the past so that they can create something that works much better than how business was done in the old days — those days are long gone.

OF: It seems that there is common ground that can be found. The Ecuadorian case, as you’re saying, is probably only a starting point, but I’m sure it’s a case from which everyone learns lessons. One would hope that the corporate world and Indigenous peoples and anyone else interested in the topic could find some common ground.

PF: There is so much common ground. Look at our own experience here in Canada. Some First Nations are involved in the oil sands. In Kitimat, First Nations own mines. And the Mikisew Cree in Fort McKay invested $500 million more of their own money in the storage tank operation. And, while some First Nations are very involved in resource development, there are many others who are opposed, because they are concerned about the impact on the climate, worried about global warming and worried about water. A number of communities have yet to recover from the devastation they’ve experienced from the extractive industries, because business has been and still is being done in a way that is inconsistent with the rights and interests of the Indigenous community.

OF: How do you bring their concerns into the conversation?

PF: At the conference, at least, we’re trying to bring as many perspectives as possible to the table. But every day opens doors for conversation.

OF: I am still wondering, how will that conversation continue throughout the conference and then beyond? Is this the beginning of something?

PF: Our hope is that this conference is the beginning of a new way of doing business. I don’t mean to be trite about it. Developments, in many cases, negatively impact the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples and we’ve had our own experience with that kind of approach in Canada. But we’re learning that there is a more positive way of engaging and interacting with each other when it comes to discussion on resources. We’re hoping that we will be able to draw on these experiences, and to host the kind of diverse discussion that can result in change.

OF: Interesting — this reminds me of some of the discussion about the Paris Agreement on climate change and the amount of money needed to achieve its goals. It is suggested that we need a coalition of business communities, governments and civil society, including Indigenous peoples, to achieve sustainable development and reverse climate change. That kind of approach would also help Indigenous communities maintain their traditional territories while improving their economic situation. There seems to be recognition that no one can act successfully in isolation, that there has to be some sort of collaboration between the corporate world and Indigenous peoples.

PF: I think you’ve focused on something of critical importance to the discussion: collaboration. It’s a burden that all of the various interest groups take on — they must find a solution that benefits everyone concerned, not just for one interest group or for one reason. I mean, the issues themselves — resources — are much broader.

OF: And more long-term too, aren’t they? There’s an element of planning for future generations.

PF: Absolutely, that’s critical. It can’t be development at all costs, it has to be sustainable development, and it has to be something that respects the rights and interests of Indigenous people today and into the future.