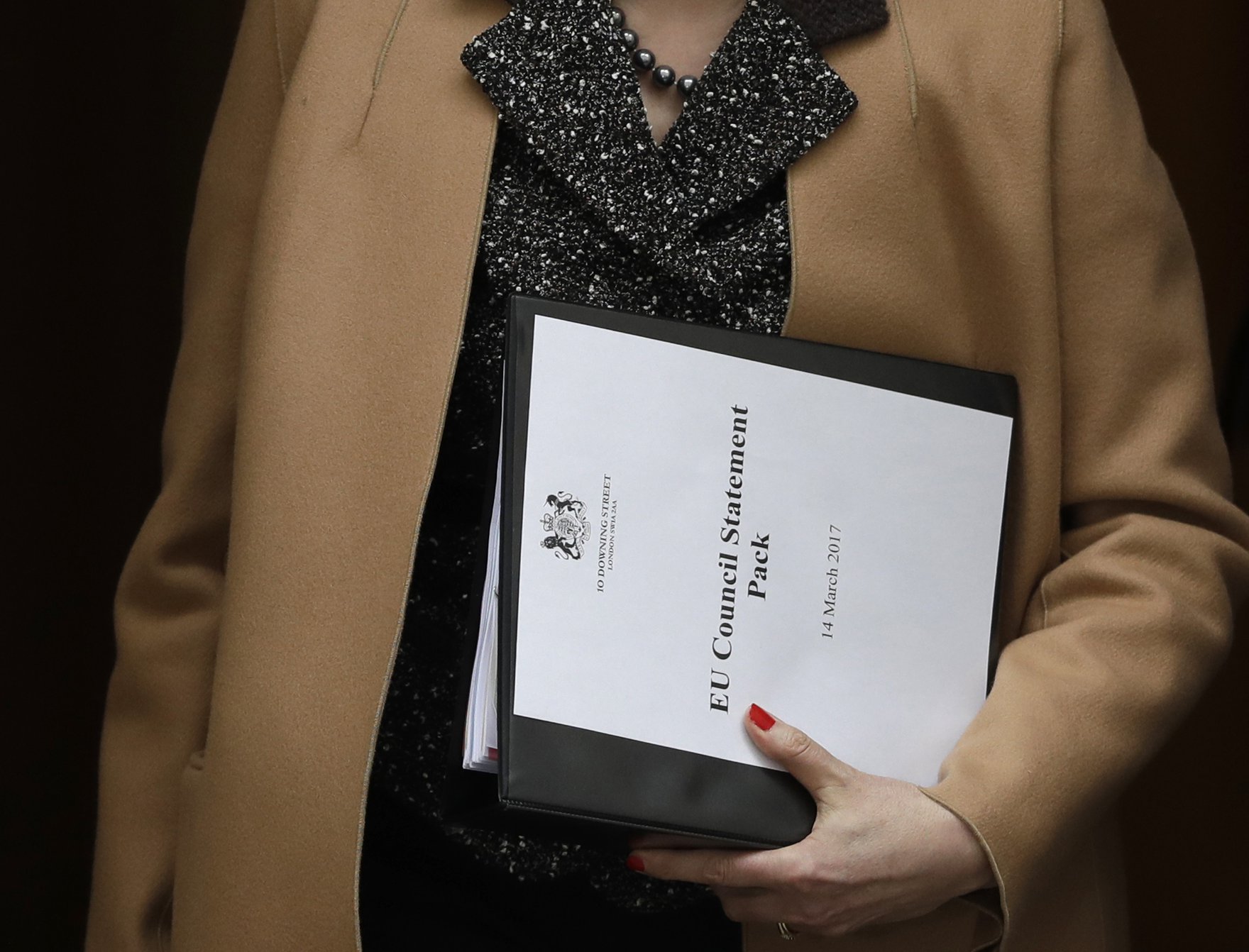

The reality of the challenges before the United Kingdom concerning Brexit appears to be gradually sinking in. Legislation authorizing the Brexit notice under article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) has passed Parliament. A sobering government White Paper on Brexit is also in circulation. The UK government, having backed into Brexit by failing to defend all that is positive in the European Union, now appears to be determined to go through with it — reflecting perhaps the long-standing discomfort of many conservative voters with “ever greater union” with Europe. Those who are opposed are in disarray, but there will be an effort made to assert that the notice under article 50 is revocable. As the complexities of Brexit are revealed, revocation of the notice may become a more popular option.

However, the debate around implementation of Brexit is not simply a UK-EU problem. Countries like Canada should be concerned. The United Kingdom is, after all, an important trading country and a nuclear power with a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, in addition to being Canada’s largest single export market in the European Union and second most import partner in the European Union (after Germany). Canada has complex trading relations with the United Kingdom and should refashion those relations in anticipation of Brexit.

Vast areas of international law applicable to the United Kingdom must be remade. The United Kingdom does not have a customs tariff. It will have to negotiate a tariff, primarily with the European Union, but also with the rest of the world at the World Trade Organization. What it wants and what it can get from others remains to be determined. This negotiation alone is an immense task. The United Kingdom will not inherit the 60 trade agreements concluded with other countries by the European Union — such as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada. Agreements will all have to be negotiated. This process takes time, effort and political will, and it could be very contentious.

The European Union has been responsible for regulation in areas such as treatment of goods and financial services, environmental protection, consumer protection, air, road, water transport, communications and telecommunications, agriculture, and so on. The United Kingdom will have to remake these regulatory systems in its own image, while at the same time maintaining rules that the European Union will recognize as equivalent, to ensure access to the EU market, which takes 44 per cent of UK exports. This will be no small achievement, and is Mission Impossible in the two years envisaged by article 50.

The European Union has also been responsible for international relations in many areas such as trade, fisheries, air transport and environmental protection. The United Kingdom must negotiate new agreements with the European Union and other countries to replace the EU agreements. In most cases, a cut-and-paste replacement is hardly the answer. Political interests in the United Kingdom, the European Union and other countries will see to that. To give but one example, what aviation rights will Canada seek in the United Kingdom after Brexit, if it is no longer guaranteed access to the complete territory of the European Union? What rights will Canada give to the United Kingdom?

Of great interest to Canada — as a source of uranium — is the notice in the White Paper announcing that the United Kingdom will be denouncing the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM). The White Paper states that the pact “provides the legal framework for civil nuclear power generation and radioactive waste management for members of the Euratom Community, all of whom are EU Member States” and acknowledges that Britain’s “precise relationship with Euratom, and the means by which we cooperate on nuclear matters, will be a matter for the negotiations.”

The Guardian noted that, once out of the European Union, UK citizens will face roaming charges on their cellphones. Every day there is a surprise.

These are but some of the challenges ahead for the Brexit-minded UK government and the international community, including Canada. The White Paper sets out the challenges but does little to suggest how they can be resolved in a two-year negotiating period. How can Canada best face the challenges ahead?

Given our complex trading relations with the United Kingdom, we need a customs agreement on trade in goods, and commitments on trade in services. We will need an air transport agreement in place the day the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, or no planes can offer commercial service. We will need an agreement on UK investment and possibly will have to review the double taxation agreement. Will the United Kingdom continue to partner with Canada on a host of international questions as varied as policy vis-à-vis Israel and climate change?

There is no easy answer, but Canada would be well served by proactively examining and clarifying its future trading relationship with the United Kingdom. One approach, which would be in the interest of Canada and the UK alike, would be the launching of negotiations to establish an Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (AFTA). Canada and the United Kingdom could make use of the Brexit crisis by pursuing the creation of an agreement covering all of Europe and North America. An AFTA would be in the interests of all countries concerned.

It is well understood that the greatest benefits of free trade are felt by neighbours who share similar economic systems and traditions. An AFTA would allow the United Kingdom to come in from the cold and at the same time create a situation where the countries around the North Atlantic could continue to remain competitive in an increasingly competitive world. The seeds of an AFTA have already been sown by CETA and by the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership negotiations between the European Union and the United States. The politics of establishing an AFTA any time soon would be daunting, but that doesn’t mean Canada and the United Kingdom shouldn’t start planning for the future.

This article has been updated from an earlier version to include direct quotes from the February 2017 UK White Paper on Brexit referring to the country's intent to withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community.