With her impressive seminal work, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, published earlier this year, Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff is asking for nothing less than a “rebirth of astonishment and outrage” to reestablish our bearings in the digital age.

And with good reason. “Surveillance capitalism” is the term Zuboff uses to describe the new economic order we find ourselves captive to in 2019 — one where human experiences are hoovered up by big tech companies, often without our knowledge, to be used as raw material to not only predict but alter our future behaviour.

It’s impossible to emerge from the 700 pages of Surveillance Capitalism and not see the devices and applications that we have embraced in our daily lives — fitness trackers, smart thermostats, digital personal assistants — through a wary, more critical lens. But what is really damning is Zuboff’s careful tracing of the role of big tech companies in surveillance capitalism’s invention and spread. Two stand out: Google, which initially invented and deployed surveillance capitalism as a way of recovering from the dot-com bust at the turn of the millennium, and Facebook (former Google executive Sheryl Sandberg is described as the “Typhoid Mary” of surveillance capitalism, moving to Facebook and helping the social media site transform its users into revenue).

Zuboff has been on a lifelong quest to answer the question: “Can the digital future be our home?” After reading her latest work, one comes away thinking that the answer is no — not without a significant reworking of the system, not without renewed astonishment and outrage.

Zuboff recently spoke to me for an hour on the phone from her home in northern New England — the chirping birds in the background tempering the serious tone of her ideas and analysis. But like the birds’ song, Zuboff wanted her message to be a reminder that not all is doom and gloom. She is optimistic that there are citizens who understand what’s at stake, and lawmakers who are willing to step forward and “put democracy above the state’s long-standing interests in protecting these private sector surveillance capabilities.”

The following is an edited and condensed version of our conversation, in which Zuboff shared an in-depth explanation of the workings of surveillance capitalism, how to “awaken the public mind” to its dangers and how to rescue the digital future for democracy.

How does this latest mutation — surveillance capitalism — fit into the long history and evolution of capitalism?

Historians of capitalism have long described its evolution as a process of claiming things that live outside the market dynamic and dragging them into the market dynamic, turning them into what we call commodities that can be sold and purchased. I analyze many ways in which surveillance capitalism diverges from the history of market capitalism, but in this way, I would say it emulates that history — except with a dark and unexpected twist. The twist here is that what surveillance capitalism claims for the market dynamic is private human experience. It takes our experience whenever and wherever it chooses. It does so in ways that are designed to be hidden and undetectable, while claiming our experience as a free source of raw material for production and sales.

Can you explain the concept of “behavioural surplus” and how it works?

As the raw material of our experience is translated into behavioural data, some of those data may be fed back for product or service improvement, but other data streams are valued exclusively for their rich, predictive signals. These flows are what I call behavioural surplus — “surplus” because these data streams are more than what is required for service improvement. These surplus data now fill surveillance capitalism’s supply chains. They are taken without our knowledge, and therefore obviously without our permission. Private experience is claimed as free for the taking and unilaterally turned into data. The data are then claimed as proprietary. [Google’s] reasoning goes, “Because experience is free, we can do whatever we want with it. We own the data we create, and we own the knowledge derived from the data.”

Imagine these supply chains growing and becoming more elaborate as interfaces are invented for nearly every aspect of human experience. This began in the online world, with our searching, our browsing, our social interactions and so forth, but these interfaces now extend to every aspect of human activity. Now we carry a little computer in our pocket. We’re out in the world, subjected to many more devices, sensors and cameras. Every “smart” product and “personalized” service is a supply chain interface extracting everything from our location and movements to our voices, conversations, gaze, gait, posture, faces, who we are with, what we’re buying, what we’re eating, where we’re going, what we’re doing in our homes, what we’re doing in our automobiles — all of these dimensions of human experience are now exposed to these interfaces that claim and data-fy our lives.

Many times, people look at Google, which was the original inventor of surveillance capitalism, and they say, “Google is in so many lines of business! They’re in smart home devices, they’re in wearables and biological devices, they’re in retail, they’re in financial transactions — their fingerprints just seem to be in every domain of human activity. This is a really diversified company, what’s with that? We thought it was a search company?”

But in fact, all of these apparently different lines of business are the same business: the datafication of human experience for the purposes of production and sales.

What happens with these data flows?

Well, the pipes filled with behavioural surplus all converge in one place, and that’s the factory. In this case, the factory is what we call machine intelligence, or artificial intelligence [AI]. The volumes of data — economies of scale — and the varieties of data — economies of scope — all flow into this computational apparatus. What comes out the other end, as in the case of any factory, are products. In this case, the products are computational products, and what they compute are predictions of human behaviour.

The first globally successful computational prediction product was the click-through rate, invented in Google’s factories — a computation that predicts a small fragment of human behaviour, which has to do with what ads you are likely to click on. It’s useful to know that based on a leaked 2018 memo from Facebook, we learned that its AI hub — its factory — chomps down on trillions of data points every day, and at the point in time referred to in this memo, which was 2017, it was able to produce six million “predictions of human behaviour” per second. That’s the scale of what we’re talking about.

And where do these predictions go?

Well, they don’t come back to us — they’re not for us. We are not their customers. We are not their marketplace. We are their source of raw material, nothing else. These predictions are now sold to business customers, because a lot of businesses are very interested in what we will do soon and later. Never in the history of humanity has there been this volume and variety of behavioural data, and this kind of computational power to monitor and predict human behaviour from individuals to populations.

Sometimes people will say, “well, these predictions are really bad, so who cares?” But that misses the point, because these platforms are a giant experimental laboratory. The predictions today are exponentially better than the predictions a decade ago or a decade before that. One has to consider the immense quantity of financial and intellectual capital being thrown at this challenge.

Never in the history of humanity has there been this volume and variety of behavioural data, and this kind of computational power to monitor and predict human behaviour from individuals to populations.

Next, these computational prediction products are sold into a new kind of marketplace: business customers who want to know what consumers will do in the future. Just as we have markets that trade in pork belly futures or oil futures, these new markets trade in “human futures.” Such markets have very specific competitive dynamics. They compete on the basis of who has the best predictions — in other words, who can do the best job selling certainty. The competition to sell certainty reveals the key economic imperatives of this new logic. We’ve already discussed a couple of them — if you’re going to have great predictions you need a lot of data (economies of scale), if you’re going to have great predictions you need varieties of data (economies of scope). Eventually surveillance capitalists discovered that the best source of predictive data is to actually intervene in people’s behaviour and shape it. This is what I call “economies of action.” It means that surveillance capital must commandeer the increasingly ubiquitous digital infrastructure that saturates our lives, in order to remotely influence, manipulate and modify our behaviour in the direction of its preferred commercial outcomes.

How exactly does this shift from making predictions to actually being able to influence behaviour occur?

When data scientists and engineers talk about machine systems, there’s a pivotal point at which you’ve been monitoring sufficiently to create a critical mass of information that can now be used to feed back into and control the machine system. They refer to this shift from monitoring to actuation. What we’re seeing is that shift, but now directed at human behavioural systems: individual, group and society.

Companies like the leading surveillance capitalists, Facebook and Google, have more information on citizens than our governments do. They can use this comprehensive knowledge to actually feed back right to that same interface from which the data is collected. Now the same digital architecture used for monitoring becomes the means of behaviour modification with programmed triggers, subliminal cues, rewards, punishments, social comparison dynamics – all of it aimed at tuning and herding human behaviour in the direction that aligns with the commercial goals of business customers.

These economies of action have now become the primary experimental zone for surveillance capitalism. The experiments conducted in this zone are not always visible to the public, but some have been hidden in plain sight. For example Facebook conducted “massive-scale contagion experiments,” the results of which were published in 2012 and 2013. In these efforts researchers determined that, number one, it is possible to use subliminal cues on Facebook pages to alter real-world behaviour and real-world emotion. And number two, it is possible to accomplish that in ways that are undetectable, bypassing human awareness. The people at Facebook appeared to be profoundly indifferent to the social contract that they violated with this work.

A particularly memorable example from the book is the case of Pokémon Go — can you explain how this mobile game was able to affect real-world activity?

From the Facebook contagion experiments we can draw a line to Google’s experimentation with economies of action, a very visible example of which was Pokémon Go, the augmented reality game incubated for many years within Google, run by a man named John Hanke, one of the pioneers of Google’s mapping capabilities – a critical factor in that corporation’s robust supply chains of behavioural surplus.

Pokémon Go was spun off from Google as Niantic Labs with Hanke as its head. It presented itself to the world as if it was some clever start-up, though Google remained its primary investor. The game brought Google’s experimentation on tuning and herding populations to the real world, to real streets, real towns, real cities, engaging families and friends in a search game without revealing that it was really the participants who were being searched. Game players were actually pawns in a larger, higher-order game aimed at providing “footfall” to establishments that paid Niantic Labs a fee for consumer traffic in exactly the same way that online advertisers pay for click-through behaviour. Niantic used gamification, with its rewards and punishments, to herd people to its real-world business customers, from McDonald’s and Starbucks to Joe’s Pizza.

The experimental zones for economies of action continue to escalate in complexity. It appears that “the city” is regarded as the next zone of experimentation. In my view, Pokémon Go was a laboratory for this larger ambition, now spearheaded by yet another Google-incubated and Alphabet-owned business, Sidewalk Labs. The city of Toronto and its waterfront are now the frontier of this experimental work.

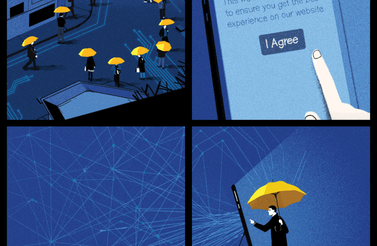

It’s worthwhile noting that the word “surveillance,” and the phrase “surveillance capitalism,” is not arbitrary. This language is not intended to be evocative or melodramatic. Had the mechanisms and methods that I describe not been hidden, there would have been resistance, which produces friction. Resistance is expensive. Everything has been designed instead for the social relations of the one-way mirror. They know everything about us, but we know nothing about them. Surveillance is baked into the DNA of this logic of accumulation. Without it, surveillance capitalists could not have achieved the staggering levels of revenues, profits and market capitalization that mark that past two decades.

I think many people reading this would look at the situation you’re describing and wonder how we possibly could have sleepwalked into this. How do you think we got here?

I’m not satisfied with any simple explanation of these developments — there are many threads that converged in history to produce the conditions in which surveillance capitalism was able to root and flourish. In the beginning, there were critical historical conditions. A regulatory framework captured by conservative economists was backed by neoliberal theories that favoured markets over the state. It demeaned and degraded, both in attitudes and in practices, the state’s ability to exercise democratic oversight over the market. As the state was diminished, economic ideology successfully tagged regulation as the enemy of innovation. These ideological conditions were essential.

Second, surveillance capitalism was invented and began to be deployed right around the same time as the tragedies of 9/11, when the state’s focus quickly and dramatically shifted from a concern about privacy to a concern about total information awareness. That shift produced shared interests and affinities between state agencies — security agencies, intelligence agencies and so forth — and these fledgling companies, with Google in the lead. Rather than to legislate for privacy, the idea became how to buffer these companies and protect them from law, thus ensuring that the new surveillance capabilities could flourish outside of constitutional constraints.

On the demand side we can see that the mechanisms and methods I describe were designed from the start to keep people in ignorance. A great deal of capital and intellect is trained on designing this entire system in a way that is camouflaged, indecipherable and undetectable. Our ignorance is their bliss.

A third factor that explains the success of surveillance capitalism is the unprecedented nature of its operations. Not only was it undetectable, but it was also unimaginable, because nothing like it had ever happened before.

A great deal of capital and intellect is trained on designing this entire system in a way that is camouflaged, indecipherable and undetectable. Our ignorance is their bliss.

Surveillance capitalism’s revenues raised the bar for tech investors. The result was its rapid spread through the tech sector. By now it marches through the normal economy too, reorganizing the profit formula in diverse industries, from insurance, to education, health, retail, finance, real estate, and much more.

This brings us to a fourth key explanatory factor: the foreclosure of alternatives. Almost everything that most people do on a daily basis simply to live their lives effectively is also a forced march through surveillance capitalism’s supply chains. If you’re getting your health data from a health platform, downloading an app to help manage your diabetes, using the school’s digital platform to get your kid’s homework, or simply organizing dinner with family and friends through Facebook, each of these simple activities draws your behavioural surplus into the miasma of surveillance capitalism’s supply operations. We protect ourselves from feeling the injustice of this situation with a range of defence mechanisms including psychic numbing. If the sleepwalking began in ignorance, it continues in numb resignation, because we can’t bear to face the facts of the world we are creating.

What are the implications of surveillance capitalism for privacy and democracy?

Privacy means that we have decision rights over our experience. As Justice [Louis] Brandeis pointed out years ago, these rights enable us to decide what is shared and what is private. Without those decision rights, we have no protection from surveillance capitalism’s economies of action, which are gradually being institutionalized as a global means of behavioural monitoring and modification in the service of its commercial objectives. These systems are a direct assault on human agency and individual sovereignty as they challenge the most elemental right to autonomous action. Without agency there is no freedom, and without freedom there can be no democracy.

This forces us to recognize that we can no longer conceptualize privacy as merely an individual phenomenon. Individual privacy solutions like data ownership, data portability and data accessibility will not be effective here. The trillions of data points ingested and computed every day or the six million predictions of human behaviour fabricated each second are not data that we are ever going to own, access or port. These have been declared as proprietary information produced from the free raw material of our experience. We can’t request this information, because we don’t even know what exists. These are not data that we gave, but rather information that has been inferred and computed based on the surplus extracted from what we gave. The result is that privacy must now be regarded as a collective phenomenon, and the work of interrupting and outlawing surveillance capitalism will require collective action and collective solutions.

At the level of the superstructure, we can see that surveillance capitalism’s extreme concentrations of knowledge –– and the power to modify behaviour that accrues to such knowledge –– reproduce the social pattern of a pre-modern and pre-democratic era, when knowledge and power were restricted to the absolute power of a tiny elite.

What all this means is that surveillance capitalism’s competitive dynamics and economic imperatives are on a collision course with democracy. It is not only we who have been sleepwalking, but democracy itself that has been sleepwalking. Our goal must be to awaken the public mind. This is not about one’s tolerance for targeted ads — we are way past that point — this is about one’s tolerance for a society that is controlled by private capital through the medium of the digital on the strength of exclusive capabilities to monitor and actuate human behaviour.

In the book you write: “Surveillance capitalism is a human creation. It lives in history, not in technological inevitability.” What does this mean for the way forward?

I am very optimistic about solutions. Many people see the conditions and they feel beleaguered and depressed and think, “Oh man, this is inevitable, how are we ever going to exist?” But I believe that is the incorrect attitude, the incorrect conclusion. [Surveillance capitalists] like to tell us that this is the inevitable consequence of digital technology — that’s just hogwash. There’s nothing inevitable about this. It’s easy to imagine digital technology without surveillance capitalism, and until Google IPO-ed in 2004, no one even had any inkling of how they were making their money.

Before all of that, the top data scientists and software engineers in the world assumed that we would be going digital, and that data would be owned and controlled by the data subject. I use the example of the Aware Home, a project from 2000 at Georgia Tech. Scientists wrote up their engineering plans for the Aware Home with all the goals and aspirations that we’d have for a smart home today: help our old folks age in place, great for remote health care, great for security, contribute to well-being in many ways. They specifically write about how devices in the walls can generate data that is quite intimate, and that obviously these will need to be private. The conception was that the occupants choose what kind of data are produced and that they are the recipients of the data. They decide how data will be used or shared. No hidden third parties and third parties and third parties. No hundreds of Google and Facebook domains sucking up all these data.

The key point is that it’s easy to imagine the digital without surveillance capitalism, but it is impossible to imagine surveillance capitalism without the digital. One is technology and the other is an economic logic that hijacks technology as its Trojan horse.

What needs to happen, then, to counter or reverse the situation in which we’ve found ourselves?

Rescuing the digital future for democracy is not the work of a single legislative cycle, not the work of a month or a year. It is the work of the next decade. I regard the next 10 years as pivotal in the contest for the soul of our information civilization. On one hand, there’s a road that leads to China, where the digital layer has been annexed by an authoritarian state power to monitor and actuate human behaviour at scale. This is not science fiction or “Black Mirror.” This is already happening on an experimental basis in China, as in the case of the Uighurs in Xinjiang, where the city has been transformed into an open-air prison of ubiquitous surveillance, or the social credit system that relies on digitally administered rewards and punishments to shape social behaviour.

In the other direction, we have the opportunity to resurrect the democratizing capabilities of the digital. Surveillance capitalism thrived during the last 20 years in the absence of law and regulation. This is good news. We have not failed to reign in this rogue capitalism; we’ve not yet tried. More good news: our societies have successfully confronted destructive forms of raw capitalism in the past, asserting new laws that tethered capitalism to the real needs of people and the values of a democratic society. Democracy ended the Gilded Age, mitigated the destruction of the Great Depression, built a strong post-war society, and began the work of protecting earth, creatures, water, air, workers and consumers... We have every reason to believe that we can be successful again.

Historian Thomas McCraw recounts the distinct approaches of regulatory regimes over the last century in the US. Early in the twentieth century it was the muckrakers and progressives who defined the regulatory paradigm. Later, it was the lawyers. Only recently in our era was the regulatory vision ceded to the economists. McCraw warns that the “economists’ hour” will certainly end, and he wonders what will come next.

The challenges of surveillance capitalism provide an answer. The next great regulatory vision is likely to be framed by the champions of democracies under threat: lawmakers, citizens and specialists allied in the knowledge that only democracy can impose the people’s interests through law and regulation. The question is, what kind of regulation? Are the answers to be found in more comprehensive privacy legislation or in the robust application of antitrust law? Both are critical, but neither will be wholly adequate to the challenge of interrupting and outlawing surveillance capitalism’s unprecedented operations.

Indeed, McCraw warns that regulators failed when they didn’t invent strategies appropriate to the industries they were regulating. We need new regulatory paradigms borne of a close understanding of surveillance capitalism’s economic imperatives and actual practices.

Rescuing the digital future for democracy is not the work of a single legislative cycle, not the work of a month or a year. It is the work of the next decade.

What should lawmakers do? First, interrupt and outlaw surveillance capitalism’s key mechanisms, starting with its supply chains and revenue flows. At the front end, we can outlaw the secret theft of private experience. This will interrupt behavioural data supply chains expressed in those trillions of data points ingested each day at Facebook. At the back end, we can outlaw markets that trade in human futures, because we know that their competitive dynamics necessarily put surveillance capitalism on a collision course with democracy. We already outlaw markets that traffic in slavery and those that traffic in human organs. The absence of human futures markets will eliminate what I call “the surveillance dividend.”

Second, from the point of view of supply and demand, surveillance capitalism is a market failure. Every piece of research over the last decade and a half suggests that when “users” are informed of surveillance capitalism’s backstage operations, they want protection, and they want alternatives. We will need laws and regulatory frameworks designed to advantage companies that want to break with the surveillance capitalist paradigm. Forging an alternative trajectory to the digital future will require alliances of new competitors who can summon and nourish an alternative commercial ecosystem. Competitors that align themselves with the actual needs of people and the norms of a market democracy are likely to attract just about every person on earth as their customer.

Third, lawmakers will need to support new forms of collective action, just as nearly a century ago workers won legal protection for their rights to organize, to bargain collectively, and to strike. New forms of citizen solidarity are already emerging in municipalities that seek alternatives to the surveillance capitalist smart city future, in communities that want to resist the social costs of so-called “disruption” imposed for the sake of others’ gain, and among workers who seek fair wages and reasonable security in the precarious conditions of the “gig economy.” Lawmakers need citizen support and citizens need the leadership of their elected officials.

Surveillance capitalists are rich and powerful, but they are not invulnerable. They fear law. They fear lawmakers. They fear citizens who insist on a different path forward. Both groups are bound together in the big work of rescuing the digital future for democracy.

In May, you attended the International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy in Ottawa. How hopeful are you that a body like this can spur international change?

There were 11 countries represented on the Grand Committee in Ottawa in May of 2019, and I expect that number to grow. Right now this is the only international body that grasps surveillance capitalism and its consequences as a critical threat to the future of democracy. They understand that fake news and political manipulation on the internet could not flourish absent surveillance capitalism’s economic imperatives. The lawmakers participating on the Grand Committee have devoted themselves to getting educated on the issues, to lifting the veil, to mastering the complexity of the backstage operations that we have discussed. I was so impressed with their dedication, insight and thoughtful hard-hitting questions. The next key challenge is how to institutionalize the Grand Committee’s role and authority as an international body bound to the future of democracy.