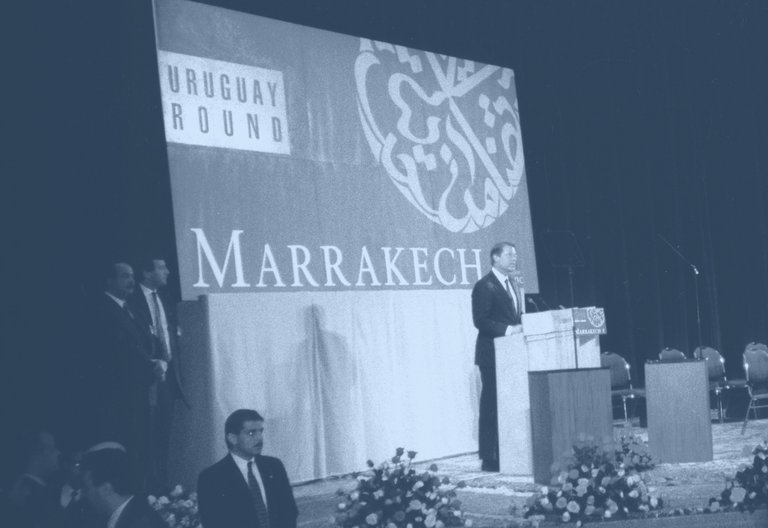

y assignment here is to muse on the likely state of international trade governance one or two years after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. Given that it will take at least another 12 to 18 months to devise a vaccine for COVID-19 (and that further waves of infection cannot be ruled out), picking a focal point four years from now — April 15, 2024, the thirtieth anniversary of the World Trade Organization (WTO) — is arguably within my mandate. The WTO’s birthday in 1994 was heralded by a ministerial declaration at the Uruguay Round’s conclusion in Marrakesh, embodying the hopes of proud new parents. But what will be left of this triumph in 2024?

Let’s start with considering the global trade in goods, which by end of year will have fallen between 20 percent and 35 percent. We can expect an incomplete bounce back in 2021, unless governments lock down economies again. Heightened uncertainty will limit corporate investment spending, which is a well-known driver of global goods trade. And worried consumers are likely to hold back on spending. At best, expect global growth in goods trade for the foreseeable future to be anemic, which in turn will tempt governments to expand tax breaks and other state support for exporters, just as they did in 2009 and the years following the last global economic crisis.

Governments will be reprising the subsidies playbook — in fact, they already are. By May 2020, the European Commission had approved just under €2 trillion of state aid to be delivered by its 27 members to European firms. Pointed debates are currently taking place in the United States over the eligibility of large firms for wage subsidies dispersed by the US Small Business Administration. That agency’s inspector general reported on May 8 that just under $100 billion had been dispersed to firms with assets in excess of $50 billion. More state largesse will be doled out as economies deteriorate. This play is only in its first act.

A variant of the old saying about terrorists applies to subsidies. One person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter. To one government, a subsidy is a prudent crisis measure; to another, it is a trade distortion. By 2024, so many subsidies will have been awarded, and so few paid back, that competition between firms will bear little relation to the merits. Many will observe the failings of the WTO’s rule book on subsidies. Complaints that some governments’ pockets are deeper than others will become another source of inequity in the world trading system. Such charges have recently been made in the European Union. It won’t take long for the rest of the world to follow suit.

Other than transport and tourism services, trade in services will continue to grow. But such trade simply does not have the salience among policy makers that goods trade has. Worse, once trade unions and populist politicians realize the impact of teleworking on domestic employment, steps will be taken to shield those only capable of low-cognitive, routine tasks from cross-border competition. These pressures will intensify once the medium-term impact of the pandemic on unemployment rates becomes evident. Recent analysis has shown that even in the flexible US labour market, it will take nearly a decade for unemployment rates to fall back to the levels seen in 2019, if past recessions are anything to go by.

The sharp downturn in the economy that followed the onset of the pandemic will further frustrate attempts to revive the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Understanding. Arguments for stronger formal mechanisms of accountability and transparency fall on deaf ears during tough times when WTO rules are effectively suspended. Third parties, including an enervated, under-resourced press, will have to shine the light on government trade malpractices. The practice of shooting messengers bearing inconvenient facts will be revived. Fear of rocking the boat will lead many officials and analysts to parrot that the system works. Having heard similar arguments a decade ago, which have been patently disproved by subsequent events (not least the Sino-US trade war), only neophytes will be convinced by such self-serving bilge.

The rhetoric that will count is that targeting China. The deeper the economic downturn, the greater the number of lives lost to the virus, the stronger will be the anti-China feeling among foreign political leaders. This won’t be confined to Washington, DC, where China’s standing is already at rock bottom. Ultimately, Brussels, Canberra, London and Tokyo will align with the United States, hitting back at leading Chinese tech companies, attempting to repatriate supply chains in sensitive sectors (the list of which will continue to grow) and repeating accusations about Chinese state and corporate malpractice. In its 2018-2019 trade war, the United States effectively removed most-favoured-nation (MFN) status from goods exported from China. It would be naive to believe that Washington’s allies would never strip MFN status from China, or to doubt that hard-liners in Beijing would as a consequence be emboldened. The motives and loyalties of those advocating international commercial engagement would be called into question.

Coming on top of intensifying geopolitical rivalry, two decades of negotiating failure and trade rules more honoured in the breach than in the observation, the COVID-19 pandemic will cruelly expose how brittle is the existing contractual view of international trade relations. The Uruguay Round in 1994 was a great leap forward — but it could not be repeated. The “triumph” of Marrakesh blinkered a generation of trade diplomats and detached Geneva more and more from developments in national capitals, where the battles for trade openness were really fought — and often lost, alas. Like ostriches, a cadre of trade diplomats, professors and officials have reacted to these accumulating problems by burying their heads in the sand, forlornly hoping that the stars will come back into alignment.

Which brings us back to the events in Marrakesh of 26 years ago. According to some participants and analysts, in 1994 the United States and the European Communities (as the European Union was then known) threatened to withdraw from the existing General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, if other nations did not join the WTO and adopt its panoply of new trade rules. Might a variant of this stratagem be deployed again?

Like a dilapidated Italian palazzo, the WTO will remain standing. Unless induced by a fit of pique, no government will leave and give up whatever rights it still thinks it has under WTO accords. More likely, a new trade club could be formed where members commit to a market-based development model, agree to deny MFN status to those who do not so commit and, effectively, side with the United States against China. If artfully designed, the new club could have common rules on carbon pricing and state support for the energy transition. Advocates of effective action against climate change and a liberal trading system would have some very difficult choices ahead of them.

And so, following a misspent youth, the child born in Marrakesh in 1994 will find itself thoroughly unprepared for life in its thirties. Its parents will be left wondering what went wrong. The rest of us will be paying the price in terms of fewer career opportunities, lower living standards and the greatest threat to peace since the Cold War.

Must the conclusion be so gloomy? As Albert Einstein argued, “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.” Creative policy makers won’t wait for the big beasts of the trading system to settle their quarrels. Instead, they will experiment with bottom-up initiatives that return the trading system to what it used to do well: limiting the uncertainty faced by traders. New Zealand and Singapore led the way with their innovative approaches to managing the pandemic. Data-driven identification of coalitions with common interests should be pursued as well. Just as the rot began in national capitals, so may the solutions be found there as well.