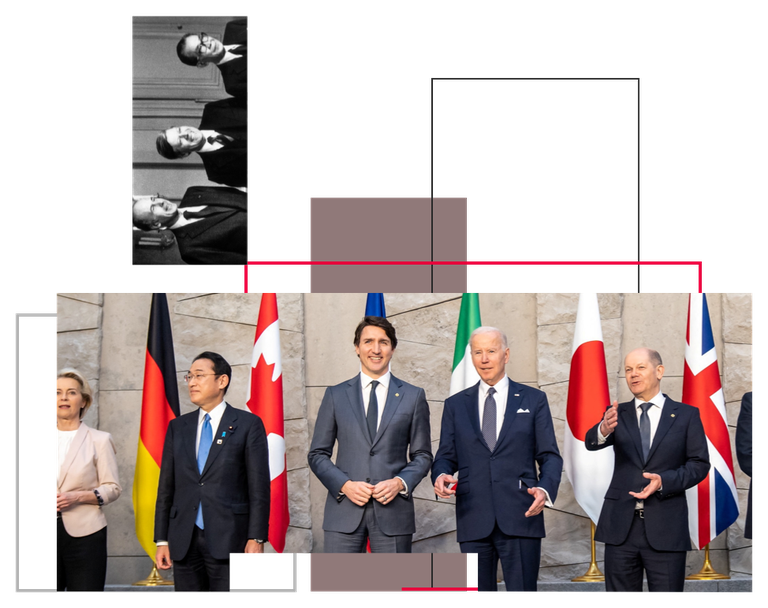

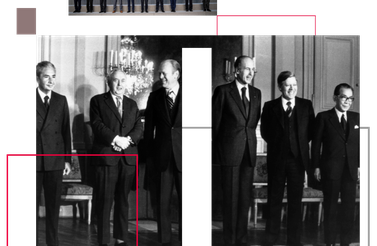

In Jennifer Bonder’s illuminating essay, we learn the fraught history of Canada’s entry into the Group of Seven (G7), an exclusive alliance of the world’s most advanced democracies by economic size. In 1975, US President Gerald Ford went to incredible lengths to orchestrate Canada’s invitation to that first summit. Yet, host country France was unconvinced, and Canada was excluded from the original meeting of the Group of Six (G6), which took place sans les Canadiens. Undeterred, Ford persisted, and invited Canada to join the Puerto Rico summit of 1976. Canada has remained a member for more than 45 years.

Bonder also outlines the impetus for that original meeting: addressing high unemployment, protectionist contagion, and the serious inflationary and energy challenges facing members. The agenda was squarely economic, and the go-to solutions were to ensure markets remained open and were further liberalized through multilateral trade agreements (G7 Leaders 1975).

In reflecting on the factors that influenced both the creation of the G7 and the conditions for Canada’s involvement, three issues seem particularly salient today.

First, there are remarkable similarities between the challenges facing the G7 at the time of its origin and those facing it today. The global pandemic has accelerated growing economic nationalism and protectionist sentiment that was already under way (Lilly 2020). More recently, high energy prices have impacted household budgets (Fernández Alvarez and Molnar 2021), and inflation has re-emerged as an impediment to economic growth for the first time in decades. In addition, Vladimir Putin’s 2022 full-scale invasion into Ukraine has thrust Russia back to the top of the list of global threats to the liberal democratic order.

There are remarkable similarities between the challenges facing the G7 at the time of its origin and those facing it today.

Second, despite facing similar challenges to the mid-1970s, G7 members today are decidedly not turning to the same solutions. No Western political leaders in 2022 dare advocate the carte blanche trade liberalization policies advocated by G7 leaders in 1975. Recent G7 communiqués have replaced 1975-era language around free and open markets with an emphasis on “fair” trade that offers “reciprocal benefits” (G7 Leaders 2018). Individual members are also less inclined to cooperate with each other, although the re-emergence of a common enemy in Putin may rally them again. The United States is increasingly turning inward economically, with President Joe Biden’s administration continuing the managed trade and protectionist Made-in-America industrial policies launched by his predecessor, Donald Trump (The White House 2021). Similarly, European members are using the region’s economic clout to advance values-embedded trade agendas, with environmental and labour strings attached. As a trade-reliant country, Canada is attempting to straddle both agendas to keep markets open for Canadian goods and services. In addition, although both time periods reflect energy challenges, the mid-1970s solution was to increase access to energy resources broadly and from diversified markets, without consideration of the climate implications. Today’s energy challenges are partially a response to those twentieth-century decisions. As countries focus on transitioning to clean energy, instability and shocks will continue until sufficient and affordable supplies, sourced from reliable security partners, catch up to demand (Yergin 2021).

The third issue contrasts the contemporary role of the G7 with its origins to consider whether Canada will continue to be regarded as a world leader in addressing global economic challenges in the future. The purpose of those original G6/7 meetings was to address the most pressing economic challenges facing liberal democracies. While macroeconomic policy and trade issues still feature in every G7 leaders’ summit and communiqué, the meetings have shifted over time to focus on threats to the international rules-based order by authoritarian countries such as China and Russia, and action on global problems such as climate change and COVID-19. This shift was deliberate: the G7 largely relinquished its economic focus by creating the Group of Twenty (G20) as the global forum for international economic dialogue, in order to include major economies such as India and China (G20 2008). For example, it was the G20 that led the response to the 2008 global financial crisis (G20 Leaders 2008) and the importance of such multilateral cooperation by a larger group of countries is well recognized. Nevertheless, the collective ambition of G20 members to articulate, address and agree on solutions to complex economic problems often remains low, reducing the forum’s productivity and impact.

Adapting the G7 as Gravity Shifts from the Transatlantic to the Indo-Pacific

In recent years, legitimate questions have been raised about the G7’s current membership, particularly as growth projections for Indo-Pacific countries eclipse those of some of the original members. Since Russia’s ousting from the G8 in 2014, and President Trump’s damaging interventions during his presidency, there has been active debate around whether G7 members represent the correct group of countries to address the global challenges of the twenty-first century. There is renewed recognition that democracy is under threat and there is a need for liberal democracies to cooperate and align their interests: any lingering doubts about this have been eliminated by President Putin. While his war against Ukraine may rally the G7 around this renewed purpose, it is against the backdrop of other musings about the potential for G7 enlargement to correct the group’s transatlantic bias. For example, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson had advocated growing the G7 into a D-10, a forum of 10 leading democracies, to confront China and improve resilience in global supply chains (Brattberg and Judah 2020). Although the D-10 has been rebuffed for now, the United Kingdom included all three potential new members in the 2021 G7 summit: Australia was invited for a third consecutive year, alongside India and South Korea. Although India is unlikely to join the G7 permanently in the near term, Australia1 and South Korea2 are poised for impressive economic growth and greater geopolitical significance in the coming decades. Their recent willingness to impose sanctions against Russia alongside G7 members suggests Australia and South Korea may be preparing to assume larger leadership roles on the global stage.

While it is too soon to understand the full implications of Putin’s ongoing war on Ukraine on global economic trends, it is likely that regional economic growth will continue to shift away from the transatlantic and toward the Indo-Pacific. Thus, an alternative to strengthening the G7 may be to develop a new set of purpose-built alliances among “like-minded” partners to address the geoeconomic challenges arising from the region’s gaining importance. There is some evidence that the Biden administration is seeking to lead such an effort, to both confront the challenge of China while also recognizing and representing the most influential economic players in the region. A review of recent US-led “minilateral” meetings suggests the Biden administration finds value in convening small groups of relevant countries to focus on emerging regional issues. For example, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (“Quad”) of Australia, India, Japan and the United States is focused on geopolitical stability in the Indo-Pacific region, given the rise of China (US Department of State 2022). In its 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy, the White House references deepening alliances with regional countries such as Australia and Japan many times (The White House 2022). However, it also mentions roles for the European Union, France and the United Kingdom as allies in those efforts. Canada is not mentioned in the 18-page document.

US–Canada Tensions over Trade with China

Contrary to the diplomatic and political capital the United States was willing to deploy in 1975 to ensure Canada’s participation at the G7, there is no evidence that the Biden administration considers Canada to be an essential member of these new rulemaking tables for the Indo-Pacific century. Rather than meeting this reality with indignation, Canada should reflect on some of the possible reasons. During Ford’s time, Canada could largely be counted on to support and advance most US priorities at multilateral tables. While Canada can continue to be relied on by the United States on many files, when it comes to trade with China, the United States regards Canada as wobbly.

For example, in 2015, President Barack Obama was deeply opposed to the creation of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and urged allies not to join (Allen-Ebrahimian 2015): while all European countries in the G7 joined anyway, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe kept their countries out. Yet, the following year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reversed his predecessor’s decision, launching Canada’s application to join the AIIB during his first official visit to China in 2016 (Lilly 2018). Under the Trump administration, Trudeau’s determination to forge stronger trade relations with China so worried US trade officials that Ambassador Robert Lighthizer insisted on a clause in the new Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA; known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, in the United States) that required parties to notify each other of plans to initiate free-trade negotiations with non-market economies.3

Even the worst trade dispute between Canada and the United States of the last decade can be traced to US anxiety about China. US Congressional Library (Congressional Research Service 2021) and Department of Commerce (2018) reports reveal that the primary reason Canada was not exempted from US Section 232 tariffs on steel in 2018 was due to concerns about Canada’s unwillingness to address Chinese overcapacity by enforcing transshipment into the United States. When the tariffs were lifted following the conclusion of a renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement deal, CUSMA, Canada had also imposed safeguards on steel imports to address trade diversion and strengthen enforcement on transshipment, thereby resolving the US concern.4

Although China’s illegal detention of Canadians Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig in 2018 has ruined Canada’s bilateral relationship with China, Ottawa has shown no sense of urgency in developing its trade and economic approach to the country following their 2021 release. Policy silence and bilateral neglect may be the government’s new strategy. Nevertheless, Trudeau’s refusal to issue a formal decision on files such as Huawei 5G has dismayed American trade and security officials. They are even more bewildered by Canada’s December 2021 decision to permit the billion-dollar sale of a Canadian-owned lithium mine in Argentina to a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Lithium is a key component of electric vehicle batteries needed to fuel the transition to clean energy vehicles. Canada declined to conduct a comprehensive national security review, which would have required formal consultations with the United States and other allies, and would have highlighted geoeconomic concerns around the proposed transaction (Standing Committee on Industry and Technology 2022). As a result, members of Congress wrote to the White House in February 2022 (Madan 2022) to question Canada’s commitment to cooperation with the United States on critical minerals (Government of Canada 2020) and on addressing the strategic threat presented by China’s dominance in the sector.

Striking the Right Balance on Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

While Canada struggles to define future goals for its bilateral relationship with China, Canadian officials are seeking to advance trade and economic relations with other countries in the Indo-Pacific (Office of the Prime Minister 2021). Although the Canada-US relationship need not be central to achieving those objectives, US interests also cannot be cast aside. As the above examples highlight, Canada has too often framed its efforts to grow trade relations with China in a manner that conflicts with or antagonizes the essential trading relationship with the United States. The United States will always be Canada’s largest and most important trading partner. In comparison to partners in the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), Canada and Mexico are uniquely dependent on trade with the United States, which represents upwards of 60 percent of bilateral trade for both countries.5 Yet, trade with the United States accounts for less than 20 percent of bilateral trade for all other CPTPP countries, most of which are more trade-exposed to China. Thus, it is essential that Canada approach its trade diversification efforts with the region in a careful manner vis-à-vis American interests.

Continuing to grow relations with CPTPP partners should be Canada’s primary trade focus in the region. Neither China nor the United States are members, providing Canada with an opportunity to work with leading members such as Japan and Australia to shape the CPTPP’s future by welcoming new members such as Taiwan (Lilly 2021). Further engagement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, South Korea and India also represent important efforts that can be pursued concurrently to the United States’ own efforts. In addition, Canada must bear in mind that it is competing with the United States (The White House 2022), the European Union (European Commission 2021), Japan (Policy Exchange 2020), the United Kingdom (ibid.) and Australia (Australian Government 2017) for influence in the region. These countries have already rolled out comprehensive and established Indo-Pacific strategies of their own that address trade and economic matters, but also collective security and defence, foreign policy, environmental action and democratic development.

Conclusion

Returning to Bonder’s essay, what is so clearly highlighted by an examination of Ford’s efforts to include Canada in the G7 is how much the forum has shifted away from its original focus on trade and the economy. Canada can now stake its own claim to major multilateral trade and economic efforts, which is obviously positive. However, it is clear from the Biden administration’s actions to create new groupings to address future geoeconomic challenges, and which do not include Canada, that there may be longer-term challenges to address. Canada should find more ways to be useful and relevant to the Americans on trade and economic files in the Indo-Pacific. Active support for Taiwan’s sovereignty, digital trade rules, energy security and supply chain resilience are all opportunities for cooperation that are consistent with Canadian priorities.

Canada-US cooperation is also important for Canada’s broader international relationships. Canada’s perceived influence with the United States is monitored by other countries, which view their own bilateral engagement with Canada partially as a mechanism to understand and influence the United States for their own goals. For example, the pursuit of bilateral trade agreements with Canada is often seen as a stepping stone to eventual negotiations with the United States. Canada’s visibly deteriorating relationship with the United States during the Trump years was less problematic when many countries were united in their opposition to his leadership style and foreign policy approach (Wike et al. 2021a). Yet, continuing negative views of the United States by Canadians following Trump’s departure from office (even compared to views of the United States by other countries) may reduce the impression that Canadians can still interpret the red-white-and-blue signals (Wike et al 2021b).

Canada is a country of citizens who at least partially define themselves culturally as “not American.” To some extent, Canadian criticism of the United States is a natural reflection of the almost familial closeness of the relationship (Alden 2021). When Trump was president, many Canadians felt they no longer recognized their American cousins, wistful for the chummy days of the Obama and Trudeau “bromance.” Yet, Canada also tends to downplay the positive spillover effects of being America’s neighbour, even during challenging periods. Canada’s bilateral challenges with its great power to the south are minuscule relative to those faced by small and middle powers bordering China and Russia. It is essential that Canada maintain perspective and recognize the tremendous security and economic benefits accrued from the relationship, even as each country pursues new trade and economic relationships independently.