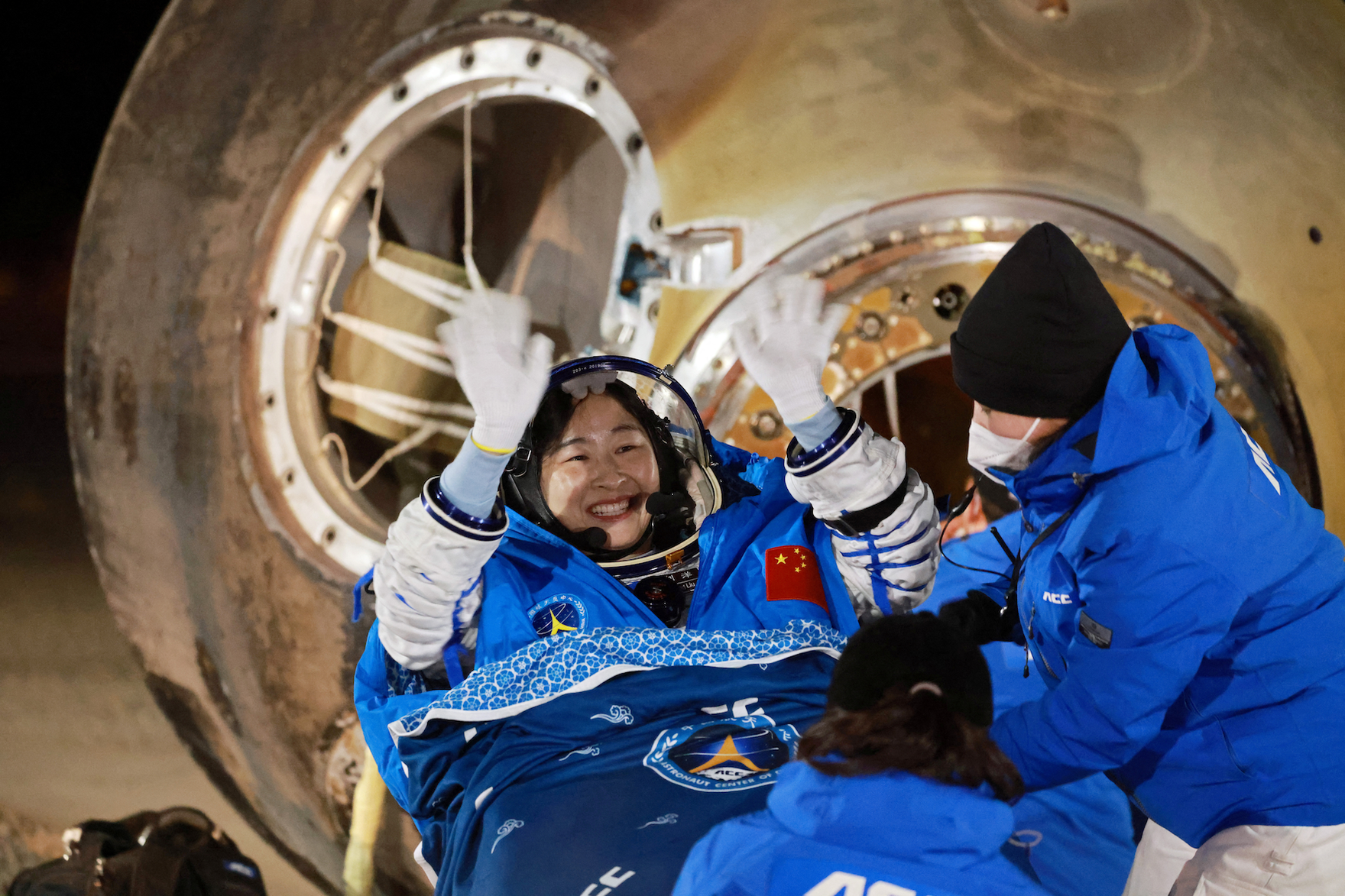

Having launched its first astronaut or taikonaut in 2003, China’s space program has evolved dramatically over the past two decades. Building on early achievements in ballistic missile and rocket programs, Beijing now aims to make the Middle Kingdom the world’s foremost space power by 2045. The country has successfully deployed robotic rovers to the dark side of the Moon (2019) and to Mars (2021), and now plans to launch probes to Jupiter and Uranus (2030). In fact, China’s space station, Tiangong (Chinese for “celestial palace”), will soon be the world’s only laboratory in low-Earth orbit.

The reality is that, despite having been excluded from the International Space Station in 2011, China is rapidly catching up to the United States in space capabilities. According to one estimate, Chinese industry is able to cycle through new space technology at twice the pace of the US space industry. Building on achievements in surveillance satellites, munitions guidance systems and space-based quantum communications, Chinese researchers now hope to develop a space-based solar power plant by 2028 and a nuclear-powered space shuttle by 2040. Here on Earth, China now leads the world in 5G (fifth-generation) telecommunications, commercial drones, Internet of Things devices, high-speed rail, facial recognition systems and mobile payments.

In the United States, President Joe Biden has introduced sweeping export controls deliberately designed to curtail China’s technological ascendance. Biden’s recent ban on advanced microchips, in concert with a broader effort at strategic decoupling, represents the early stages of a new technology cold war. While technology decoupling will undoubtedly slow China’s rise, it will not stop it. Indeed, what seems clear is that cooperation between the two superpowers is winding down. Notwithstanding photo ops at the Group of Twenty Leaders’ Summit in Bali, both countries understand that they are now competing to shape a new multipolar order.

The New Cold War

So far, Beijing has avoided direct economic warfare with the United States, but growing technology rivalry reflects an increasing awareness that technological leadership determines global leadership. China has forged a new strategic alliance with Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, with ambitious plans to explore the Moon. Together, the two countries hope to launch a permanent lunar base station by the end of the current decade. Beyond its scientific and commercial value, the dual-use potential of space makes the space economy critical to military operations, including operations in Ukraine.

Of course, the United States and China are not the only countries interested in space. Rapidly evolving orbital and lunar programs in India, Japan, Europe and the Middle East represent enormous centres of commercial and scientific investment. Saudi Arabia alone plans to invest $2.1 billion in its fledgling space program. Beyond nation-states, commercial pioneers such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, SNC, OneWeb and Boeing are pouring billions of dollars into frontier industries spanning satellite infrastructure, telecommunications, asteroid mining, space tourism, energy generation and reusable rockets.

While telecommunications is forecast to drive the lion’s share of economic activity, commercial interest in mining asteroids for cobalt, iron and nickel as well as precious metals (gold, silver and platinum) is growing. The global space economy is currently valued at $469 billion and is expected to rise to $1 trillion over the coming decades. Given the enormous scale and scope of the space economy, questions regarding the governance and regulation of space have become unavoidable. Notwithstanding the UN-sponsored Outer Space Treaty of 1967, there remains a legal vacuum in the governance of space that could enable a chaotic global “gold rush.”

Governing Space

What is already very clear is that new rules, new protocols and new laws governing the space economy are needed. The general lack of clarity over space-based resources and the ambiguity surrounding the laws that govern space present substantial challenges. Introducing guardrails in mitigating a global space race will be critical to reducing the potential for armed conflict. As a global middle power, Canada could be an important actor in guiding this process.

Competition between the United States and China will almost certainly drive the militarization of space. This includes space-based applications of artificial intelligence, robotics, drone technologies, telecommunications, quantum computing and nanotechnology. To be sure, the strategic rivalry between the world’s two superpowers could mirror the twentieth-century Cold War in very destructive ways. Competition between the United States and the Soviet Union catalyzed revolutionary advancements in telecommunications, semiconductors, satellite navigation, weather forecasting, rocket technologies and the internet itself. But it also saw trillions of dollars sunk into a global morass of reckless military spending.

Taken as a whole, the very real potential for cold war escalation signals the need for formal oversight in negotiating a normative path forward. As with the Cold War of the last century, confidence-building measures that support scientific exchange and multilateral cooperation will be critical to avoiding the weaponization of space. Cooperation could include the development of a common vocabulary for managing the geopolitical risks posed by space-based industries. It could also include a formal ban on space-based weapons — one that mirrors treaties on weapons technologies in other domains (for example, biological weapons, chemical weapons and anti-personnel landmines).

Fortunately, this is not the first time that nation-states have been confronted with a new multipolar order impacting global security. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the world’s most powerful countries — the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, China, France, Germany and Japan — oversaw global governance of nuclear weapons, chemical agents and biological warfare. Then, as now, the world must act collectively to safeguard the future of global peace and security.