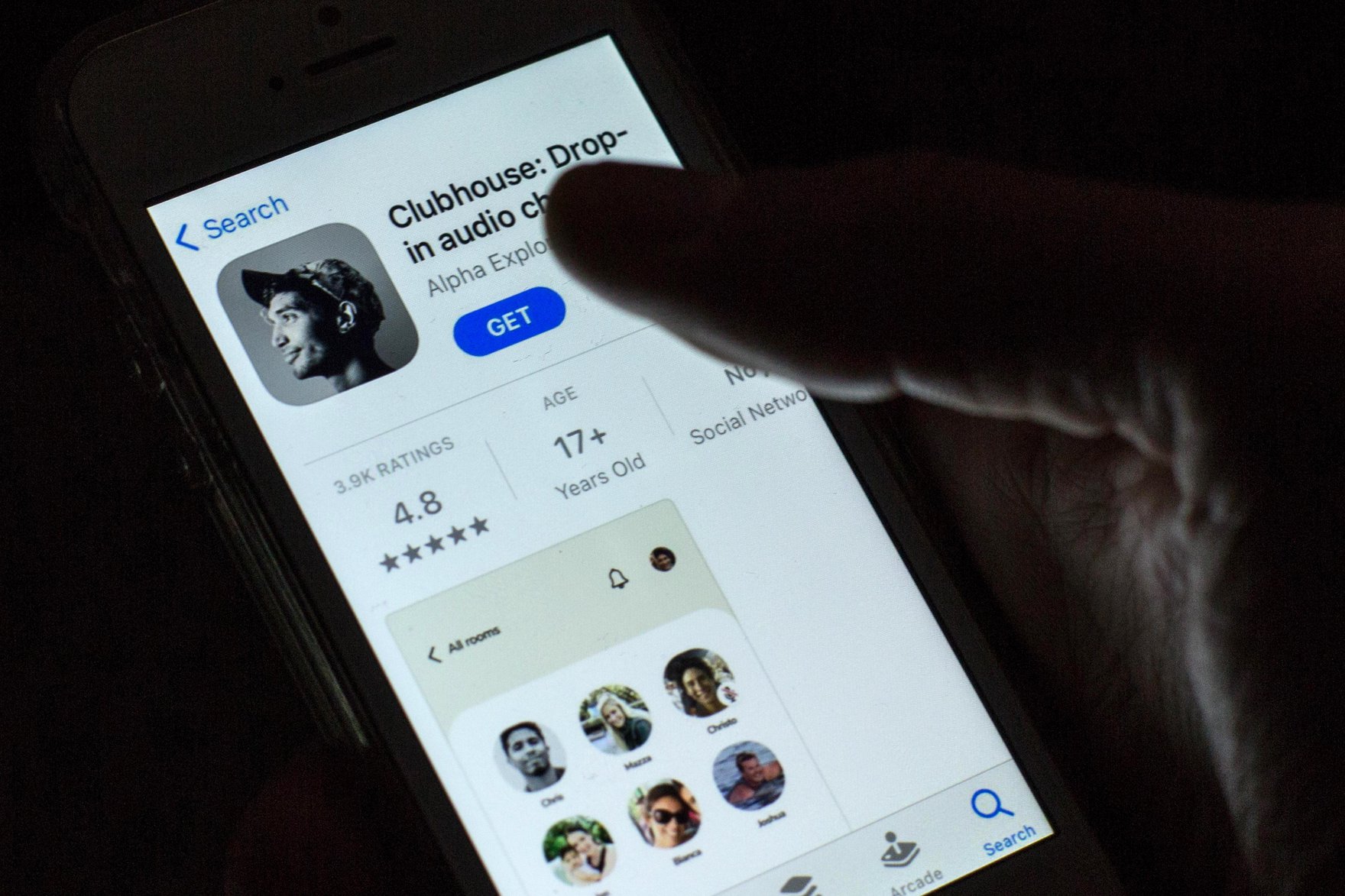

Clubhouse is a small but quickly growing audio-based, invite-only mobile chat app and social network owned by Alpha Exploration Co. In what feels like a combination of talk radio and podcasting, the app allows its users to weave in and out of digital spaces known as “rooms” to listen in on live conversations between featured speakers, known as “hosts,” and their guests, as well as to join “clubs” of interest. Clubhouse rooms and clubs span many topics, everything from vegan fashion to bitcoin, theoretically offering something for everyone.

Co-founders Rohan Seth and Paul Davison launched the app for iOS in beta in March 2020. After a slow start, downloads began to soar in 2021, due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic with its resultant captive audiences desperate for connection, and some high-profile audio chats, such as the one hosted by Elon Musk on January 31. Clubhouse is now estimated to have more than 10 million active weekly users and Alpha Exploration Co. is rumoured to be valued at nearly US$4 billion in a round led by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

Despite its high valuation, Clubhouse’s founders and backers have demonstrated limited regard for privacy, security and accessibility to date, and appear to have learned little from the missteps of earlier platforms on perennial challenges such as content moderation, facing them sooner than platforms have in the past. As one reporter observed, “Clubhouse [is] speed-running the platform life cycle.” As a result, Clubhouse is an important case study in the limits of our approaches to data governance in the face of Silicon Valley’s indefatigable ethos.

The app, which initially launched without a privacy policy, leveraged “dark patterns” and algorithmic discoverability tactics to gain access to users’ phone contacts and even required users to grant this access before they could invite friends to the platform.

It is clear that Clubhouse was not designed with privacy in mind. The app, which initially launched without a privacy policy, leveraged “dark patterns” (manipulative product design) and algorithmic discoverability tactics to gain access to users’ phone contacts and even required users to grant this access before they could invite friends to the platform (those contacts, of course, had no opportunity to consent to that sharing or to even know it was happening). The app also broadcasts a new user’s presence on the platform, one of its many notifications and alerts, and provides no way to block harassers or abusers. Audio files are recorded but not encrypted, and the app also uses invasive tracking tools, including cookies and pixel tags.

After pushback from users and privacy advocates, Clubhouse made some minor tweaks; it now allows users to manually enter phone numbers to invite their friends and contacts. It is uncertain whether this change actually prevents Clubhouse from harvesting the contacts of its users even when they do not opt-in. These concerns are particularly problematic in Europe, where the law mandates data protection by design and default. Clubhouse’s privacy policy, which is only available in English, does not reference European regulations or provide any way for users to exercise their data protection rights.

Security experts have raised concerns about issues beyond the privacy challenges. In February, researchers at the Stanford Internet Observatory confirmed that Clubhouse was transmitting audio and other personal information in plain text to servers in China, making the information potentially accessible to the Chinese government. The app has since been banned in China after hosting conversations about alleged Uighur internment camps and other politically controversial subjects, which could clearly have put activists and dissidents at risk. More recently, a database containing the records of 1.3 million Clubhouse users was posted on a popular hacker forum, including user names, profile photos, social media handles, account creation details, contacts and more, soon after similar leaks of Facebook and LinkedIn user data.

According to security experts, “the Clubhouse SQL database used sequential numbering in the creation of user profiles, which allowed scrapers relatively easy access with basic tools [through] a simple script that adds one number to profile links.” Clubhouse CEO Paul Davison vehemently rejected characterizations that the app had been breached or hacked, stating, “The data referred to is all public profile information from our app, which anyone can access via the app or our API.” Davidson was essentially defending “scraping” — the practice of extracting publicly available, non-copyrighted data from the Web. Whether technically a breach or not, the incident has breached the trust of many of its users, who did not reasonably expect their information to be used in this way.

It also demonstrates a growing chasm between attitudes in the United States and Europe about data governance, as Silicon Valley continues to export its technology and ideals around the world. Scraping is the same technique that controversial start-up Clearview AI, popular with law enforcement, has used to amass its facial recognition database. Although it’s received cease-and-desist letters from Facebook and Google (who themselves would not exist but for scraping and, in the case of Facebook, scraping non-public information), Clearview AI defends its practices on First Amendment grounds. In Europe, where data governance is more concerned with the fundamental rights of individuals than with the rights of corporations, techniques like scraping and the repurposing of publicly accessible data conflict with core principles in the General Data Protection Regulation, such as purpose limitation, notification and consent requirements, the individual’s right to object to certain processing and more. Clubhouse is already under investigation by data protection authorities in both France and Germany for violations of data protection law.

But Clubhouse’s gaslighting on privacy and security concerns pales in comparison to its disregard for accessibility. In its quest for exclusivity, Clubhouse has managed to exclude large swaths of the population. The audio app, only available to iPhone users, was designed and deployed with virtually no accommodations for individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing, visually impaired or who have certain other disabilities. Competitors such as Twitter Spaces, while not perfect, at least allow users to turn on captions and share transcripts, among other features, demonstrating that accessibility in audio apps is possible. As one expert put it, “The app’s founders — and their venture-capital mega-backers in Andreessen-Horowitz — don’t know enough and don’t care enough to make accessibility the priority it deserves.”

It might be tempting to excuse these challenges as teething problems that will be worked out over time. But there are two main problems with that view. First, these problems are not new. Public opinion and attitudes about privacy and security have evolved significantly since Mark Zuckerberg launched the Ivy League-only TheFacebook.com nearly two decades ago. Law- and policy makers are increasingly concerned too, and more than 130 countries around the world have introduced modern data protection and privacy laws for the digital world. And yet, much like early Facebook — which was also backed by Marc Andreessen, before he formed Andreessen Horowitz — Clubhouse is built on a combination of engineered hype, artificial scarcity and exclusivity, and the fear of missing out, with little regard for privacy, security or accessibility. In fact, in an unusual move for an app still in its beta phase, Clubhouse has already launched an influencer program. In other words, Clubhouse is following the standard Silicon Valley playbook.

That Clubhouse was designed and rolled out this way now shows how little Silicon Valley and its venture capital backers have learned about what true “innovation” looks like, or perhaps, how little they care. A truly innovative product would learn from the mistakes of predecessor platforms and would focus on things like privacy, security and accessibility. Instead, Clubhouse is yet another example of technology designed by, and largely for, privileged, white, Western and able-bodied men. In many ways, Rohan and Davison, who met at Stanford and have an estimated nine failed apps between them, exhibit the naive optimism of many Silicon Valley founders who only see the good in tech and represent persistent disparities in the venture capital world. In 2020, only 2.3 percent of all venture funding went to female founders (down from 2.8 percent in 2019, as women were hit harder by the pandemic).

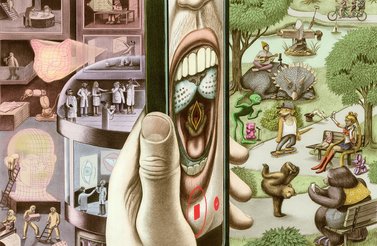

It’s easy to think that if policy makers, developers and users could all go back to the beginning of Facebook, they would do some things differently. But, as Clubhouse demonstrates, we are, once again, quick and eager to trade in our purportedly core values of privacy, security and accessibility for yet another shiny toy. And while it is one thing to ask people to go without their Facebook or Google products and services, now that these platforms have become so embedded in their daily life, it is another to ask them to abstain from Clubhouse. In this moment, before users have a compelling need to be on these platforms (because everyone else is there), and before Clubhouse becomes too big to fail, we still have a choice.

This is our opportunity to demand more and to demand better. After all, if Clubhouse users do not demand these things from the outset, why should the policy makers whom we ask to regulate these technologies care? As the author and Princeton professor Ruha Benjamin so eloquently puts it, “Most people are forced to live inside someone else’s imagination.” For now, at least when it comes to Clubhouse, we still have a chance to reimagine.