By the time this post appears we may well know who will be nominated to replace the current governor of the Bank of Japan who, along with two deputy-governors, will relinquish his position a few weeks before his term is due to expire. Clearly, the current senior management is being swept away as a consequence of the recent change in government in Japan.

Whatever one thinks of the first weeks of the new Japanese government and its Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, one has to be impressed by the aggressiveness with which the government is trying to pursue a different economic strategy from the ones followed by his recent predecessors. Nicknamed “Abenomics” the newly installed government wants to reinvigorate the Japanese economy mired in deflation and seemingly slow growth, dubbed the ‘lost decades’. As I understand it, the strategy consists in pursuing a more aggressive monetary policy than has been carried out to date, adding further stimulus via some expansionary fiscal policy, as well as introducing structural reforms, such as regulatory changes, to provide incentives for the Japanese economy to grow more quickly.

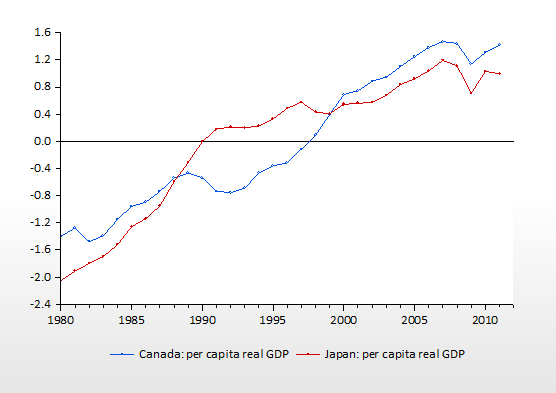

There continues to be widespread misunderstanding about Japanese economic performance. The figure below plots, on a normalized scale to permit a direct comparison, real per capita GDP in Canada and Japan since 1980. To be sure, there are differences but, on the whole, the Japanese economy seems to have done reasonably well.

Source: February 2013, International Financial Statistics CD-ROM and author’s calculations; Real GDP (2005=100) deflated by population and normalized (i.e., demeaned and deflated by the respective series’ standard deviations).

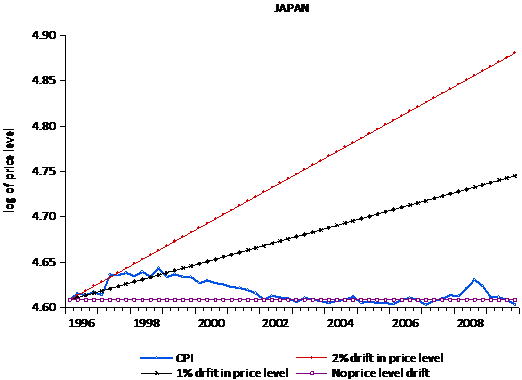

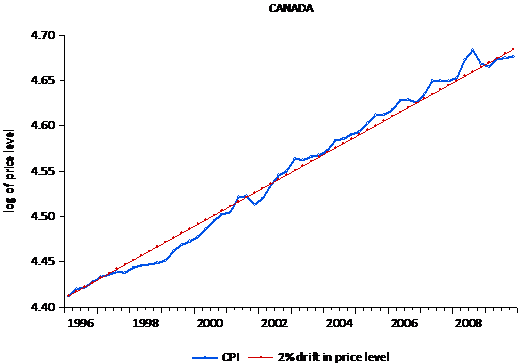

Why then worry about deflation? Part of the worry is that deflation is somehow synonymous with poor economic performance and generates the wrong incentives, in particular, to invest and purchase durable goods. The story goes something like this: firms, and households, are likely to postpone some forms of spending if they believe that prices will be lower in future. The figures below show the contrast between price level behaviour in Canada and Japan. Whereas prices in Canada have been rising remarkably closely to the Bank of Canada’s inflation target of 2%, the Bank of Japan’s record comes closest to a 0% inflation target. The inflation record is nowhere near as dire as some seem to think and there is little evidence of deflation spiralling out of control. Equally important is that Japan’s population is ageing rapidly —more so than Canada’s population — and economists are still grappling with what effects of this type of development will have on consumption, investment and economic growth.

Source: P.L. Siklos (2013), “Communication for Multi-Taskers: Perspectives on Dealing with Both Monetary Policy and Financial Stability”, working paper. The straight lines show what the price level would be under different scenarios for inflation.

Although ambitious, and far from being implemented as this is written, what has made waves has been the pressure applied to the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to raise its inflation objective to 2% (from a 1% goal). The minutes of the January meeting of Bank of Japan’s policy making committee record that “...most members expressed the view that it was desirable to designate the specific numerical expression for price stability as 2 percent in terms of the year-on-year rate of change in the CPI.” The decision by the BoJ to acquiesce to the newly installed Prime Minister’s demands naturally made news around the world and more than a few observers (e.g., Paul Krugman) wrote approvingly of the change of heart.

Nevertheless, before reaching the conclusion that all will be well in Japan there are several reasons to worry, even if the other elements of Abenomics are eventually put into place. First, the decision by the BoJ to raise the inflation target was made quite reluctantly and it is unclear from the minutes of the BoJ’s January meeting that the Board was enthusiastic about the change. Consider some of the contents of the minutes leading up to the decision to agree to a higher inflation target:

“The Bank of Japan Act stipulated that the Bank should conduct monetary policy based on the principle that monetary policy was aimed at "achieving price stability, thereby contributing to the sound development of the national economy." According to the Bank's Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior, approximately 80 percent of the respondents — irrespective of sex or age — consistently viewed a price rise as ‘rather unfavorable’."

The gist of the statement is that inflation for its own sake need not contribute to economic performance and the public does not appear to equate it with better economic performance.

Second, the decision comes after many months of political pressure on the BoJ and concerns expressed about the loss of independence of the BoJ. As I have pointed out in earlier posts, economists view the independence of the central bank as referring to a measure of autonomy to carry out day to day policy. Independence does not mean that the government should not change, say through legislative actions, the overall objectives of the central bank, such as setting an inflation objective. What economists do believe, generally, is that the objective of monetary policy should be set jointly with the government, as is the case in Canada. Instead, in Japan, the government is talking at the central bank via the public medium instead of having a reasoned discussion with the BoJ about setting a new course for monetary policy in light of the apparently strong mandate given to Abe in the last election. This strategy becomes even stranger when, unlike central banks in the rest of the advanced economies, it is realized that government representatives attend the BoJ’s policy meeting (i.e., from the Ministry of Finance and the Cabinet Office). It is, therefore, highly unlikely that government officials are unaware of the thinking inside the BoJ.

Consequently, so far it is looking like Prime Minister Abe is engaging in ‘cheap talk’ or trying (successfully it seems so far) to score political points rather than engage in a more serious and substantive debate about the contribution of a higher inflation objective to spurring economic growth in Japan. It is hard to see how this kind of behaviour, even if politically desirable, accomplishes the task of changing expectations about the ability of monetary policy to help Japan escape from deflation or, to coin Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney’s recent phrase, assist Japan’s economy to reach “escape velocity.”

Indeed, it is telling that the minutes of January’s BoJ Board meeting explicitly warns elected policy makers that,

“Many members —referring to the fact that the government had shown its intention to aggressively pursue steps for strengthening the competitiveness and growth potential of Japan's economy — expressed the opinion that, as such steps made progress, the actual rate of inflation would be expected to rise and, accordingly, the inflation rate at which the general public perceived price stability would be likely to rise as well.”

Put differently, the BoJ’s Board is arguing that inflation will rise after structural reforms have had a chance to impact the economy while the mere declaration of a 2% (or higher) inflation objective may end up sounding like empty words.

As someone who views inflation targeting as ‘best practice’ in monetary policy I do, however, worry about those who believe that the mere declaration of an inflation target is sufficient. It is worth reminding readers that inflation targeting came into being for at least two reasons: the failure of alternative monetary policy strategies, such as exchange rate or money supply targeting and, perhaps more importantly, because inflation was too high and the only way to convince the public that the central bank was able to deliver low and stable inflation was through a joint commitment with government to deliver such an outcome. The circumstances in Japan, however, are different. Not only is the goal to raise inflation — which inflation targeting was arguably not designed to do — but whereas generating lower inflation through tight monetary policy is easy enough (albeit potentially painful), there is relatively less room to deliver easier monetary policy once interest rates have reached the zero lower bound and vast amounts of various private and public assets are on central banks’ balance sheets.

Time will tell, of course, whether Japan will return to higher economic growth. In the meantime it seems that it is the rest of the industrial world that is headed towards Japanese style economic performance.