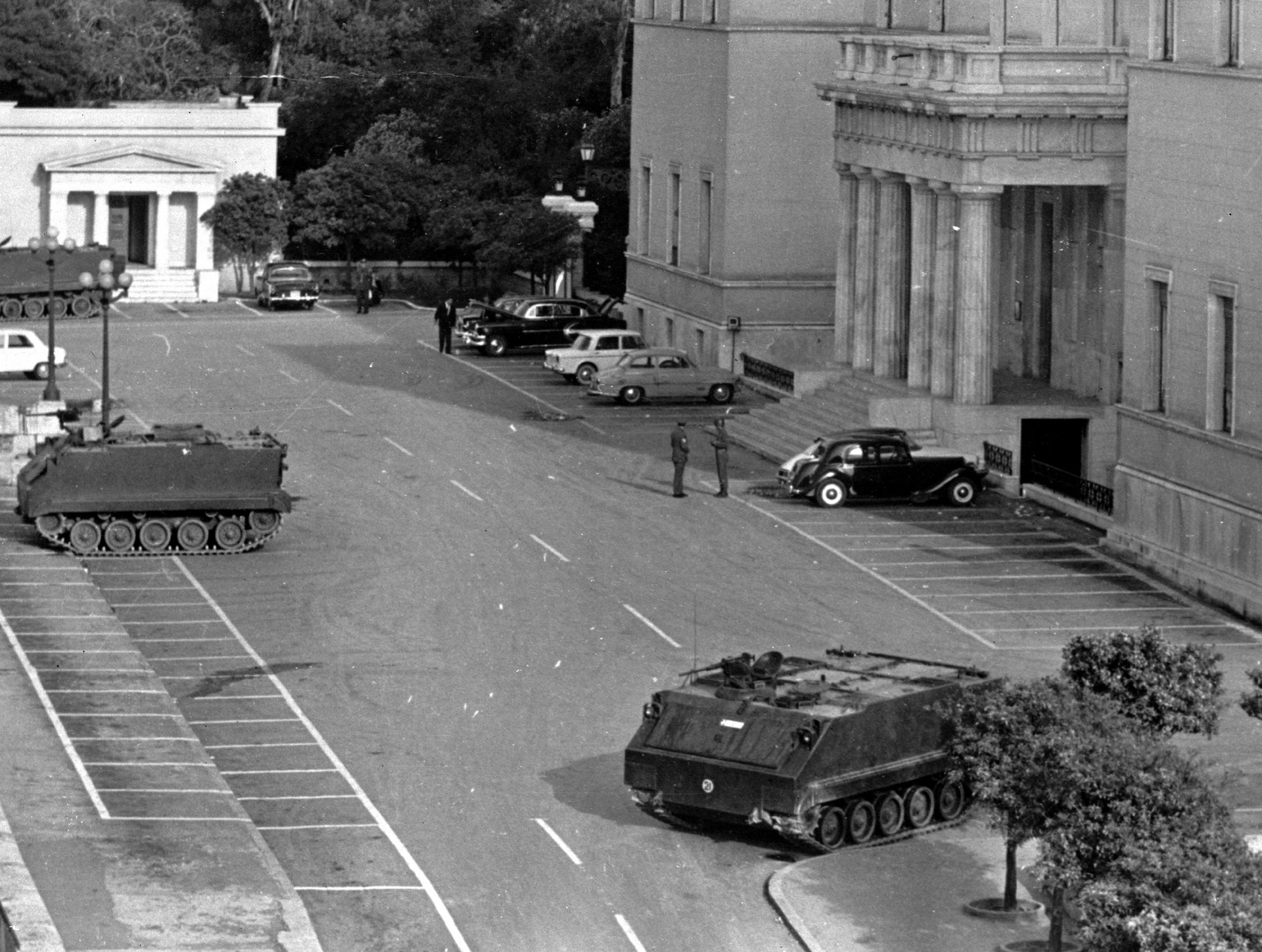

On April 21, 1967, a group of military officers overthrew the government of Greece. The fiftieth anniversary of that event should be a relatively happy one. Although the colonels’ regime was cruel, it proved to be the last European manifestation of what can justly be called fascist thinking. Around the world, the authoritarian approach lost out to the model offered by prosperous, liberal and democratic Europe — at least until now.

The 1967 coup was another unhappy chapter in the fairly dismal history of modern Greece. Since declaring independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821, the country has been blighted by unstable governments, violent civil strife, military failure and almost incessant sovereign bankruptcy.

The last Greek putsch, though, was not merely more of the same. It was the end of a global era. The Greek colonels described themselves as fervently anti-Communist, but their right-wing ideals agenda was as much positive as negative. The dominant themes were extreme nationalism, traditional moral values and individual discipline.

The Italian Fascists were the first European party to bring these ideas into power. Benito Mussolini’s state was going to be more than merely dominant in every aspect of life. It would also be inspirational. The ideological opposite of decadent modernism, Fascism was supposed to restore lost national greatness. Military strength would be a sign of the new thinking’s success.

This ideology was very influential in many countries through much of the twentieth century. At the edge of Europe, the Turkey of Atatürk was proto-fascist. Adolf Hitler copied many of Mussolini’s techniques. In Spain and Portugal, Francisco Franco and António Salazar, respectively, carried on with much of the tradition until well after World War II. Arab and Hindu nationalists and many of the military leaders in South America were also more or less under the influence.

By 1967, though, the ideology’s appeal was dwindling. The Greek military leaders did their best to keep the flame burning. They promoted the Greek Orthodox national religion. They mandated the official use of Katharevousa, a supposedly more dignified version of the Greek language. They persecuted opponents. They talked endlessly about restoring lost national glory. But even they promised a return to democracy, and persisted with the pre-coup government’s plan to join the European Economic Community, the predecessor to today’s European Union and the embodiment of anti-fascist modern ideals.

Despite presiding over rapid economic growth, the colonels never inspired much popular enthusiasm. Greece has had many troubles since the military regime collapsed in 1974, but the country’s leaders have all tried to stay on the path toward the European mainstream. And the Greek junta was the last of its kind in Western Europe. The only subsequent military coup, in Portugal in 1974, was by left-wing soldiers against the fascist-style Estado Novo. Over the next few years, right-wing insurgencies failed in Spain and Italy. Since then, nothing.

This liberal mainstream also became the global gold standard. When the Soviet bloc fell apart, there was some talk of a third way, but it faded fast. The vast majority of the people in former Communist countries simply wanted the Western European system. In every continent, military coups became less common. Almost every government claimed to be aiming at the liberal state — parliamentary democracy, a large and well-regulated private sector and an extensive welfare system.

Is this global consensus now falling apart? It is certainly on the defensive. Russia, Poland, Hungary, Turkey, the Philippines and perhaps India have moved in nationalist-authoritarian directions. China’s political liberalization, never more than tentative, has been firmly reversed. The trends look bad in South Africa and much of the Middle East. Populist-nationalist movements have made headway in Europe. And the new US president revels in authoritarian verbiage.

Still, today’s illiberal democracies are, at worst, only pale imitations of the old fascist states. Their leaders hold elections, support some private enterprise, are highly selective in their political persecution and are cautious about military conflicts. Even President Donald Trump seems more chaotic than fearsome.

The reason for the tepid commitment to illiberalism is not hard to find — its rival’s success. When fascists first rose to power in Europe, the establishment had just presided over one world war and a huge depression. Now the liberal offering suffers from nothing worse than poor labour markets, strains in the welfare state and a tired ideology. Would-be dictators are cautious about trying a different model.

Besides, the new authoritarians also suffer from ideology fatigue. After World War II, no one can put much faith into anything even vaguely resembling Nazism. Today’s authoritarian leaders lack the blind confidence needed for real extremism.

Greece is typical of this more moderate world. The ruling party, Syriza, came in to power with revolutionary nationalist rhetoric, of the left, but it has largely followed the European Union’s orders. At the other extreme, the right-radical Golden Dawn has made little headway.

The world’s all-too-numerous aspiring strongmen should learn the lesson from Greece’s last fling with autocracy, a half-century ago. The liberal way is far from perfect, but at least for now there is no viable alternative.