Facebook is engaged in a dance with regulators, moving back and forth on the idea of inevitable regulation while remaining vague on specifics and taking careful steps to limit what regulators can do.

This dance is, in part, a distraction. Some of Facebook’s recent actions demonstrate that the tech giant may be working to appear as if it is engaging in better behaviour to buy some time for efforts to further evade and delay regulations.

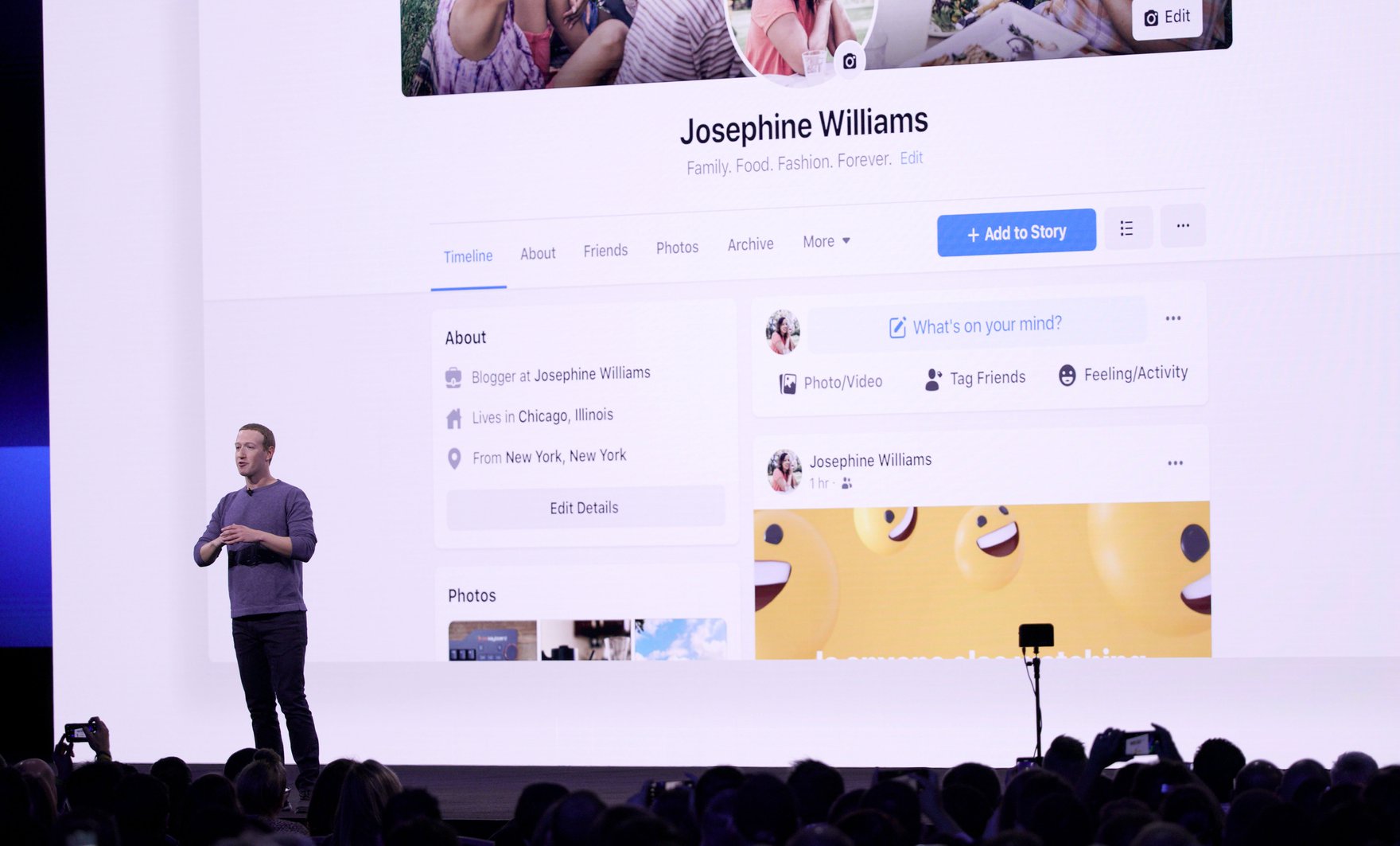

For example, at the company’s annual developer’s conference, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said that “the future is private.” This declaration, amid the announcements of a major redesign of the company’s primary product — Facebook — and its quick moves to integrate and consolidate their messaging products, was made with regulators in mind.

Facebook is careful about what it discloses to the public. Given that the company’s credibility and trust are at an all-time low, those communications must be treated with skepticism and scrutinized.

Canada’s Privacy Commissioner seems to be taking this position. The federal commissioner, along with British Columbia’s Information and Privacy Commissioner, recently concluded a joint investigation into the company’s activities surrounding the Cambridge Analytica scandal: “The stark contradiction between Facebook’s public promises to mend its ways on privacy and its refusal to address the serious problems we’ve identified — or even acknowledge that it broke the law — is extremely concerning.”

Focusing on Groups at the Expense of the Newsfeed

When Zuckerberg said “the future is private,” he was likely expressing an idea entirely different — and much more self-interested — than a newfound concern for protecting personal data. Specifically, Facebook is moving away from “the newsfeed” — the place where users see status updates and posts from friends and pages — to a focus on the platform’s group and messaging functions — private or semi-private moderated spaces in which fake news, misinformation and extreme content thrives.

Rather than acknowledge the platform’s role as a de facto digital commons, Facebook is attempting a retreat from the notion of public space, back to a semi-private, almost tribal space, of groups and pages. Instead of coming up with a responsible governance model to deal with fake news, abusive behaviour and extremist content, the company is hoping that individual users will do so via moderation of groups and communities.

With this move, Facebook seems to be working to distinguish itself from the identity — and responsibility — of a publisher or media company. Instead, the company clings to the innocence of the platform identity; users are responsible for their posts and actions.

With users herded into groups and private messages it will also be harder for researchers and regulators to understand and intervene in any Facebook-facilitated activity.

Integrating Products to Evade Regulation

Facebook is also facing pressure when it comes to its near-monopoly over digital messaging. The company’s acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp are clear examples of the company’s ability to acquire any competitor that may pose a threat. In response, regulators have discussed breaking up Facebook to limit the company’s influence on the communications industry.

Facebook’s newly announced intention to integrate these products, however, won’t make it easy. The consolidation — while billed as a tactic to ensure users’ privacy and security — is likely to benefit Facebook’s larger agenda and bottom line, too.

This raises some larger questions: are regulators nimble enough to regulate a company like Facebook? Or will such companies simply continue to adapt and change to avoid a regulation as soon as it is proposed?

Regulating Analytics and User Research

Facebook has a privileged position in another market: analytics.

In 2013, Facebook bought an Israeli analytics firm called Onavo, which provided an app (and later a virtual private network) that helped users get a faster mobile experience, in exchange for information on which apps they were using. For several years Facebook used this service to identify what new apps were trending so that they could stay ahead of the market.

After getting caught for using Onavo to spy on teenagers without their informed consent, Facebook announced that they would stop using Onavo in this way but would continue to engage in similar forms of paid or compensated research.

The use of analytics and research services in this manner raises not only privacy concerns but antitrust concerns as well. As regulators contemplate how to ensure that Facebook does not abuse its power or market position, the company’s use of mobile analytics must also be considered.

These regulatory hurdles — corporate restructuring, clever consolidation and ever-increasing market power — are Facebook’s bread and butter. The company has been good at staying a step ahead of regulation, but its veil of good corporate citizenship is getting thinner; policy makers and citizens alike are beginning to ask tough questions of technology giants.

The US Federal Trade Commission is in the final stages of negotiating a settlement with Facebook. The company has indicated it expects to arrive at a fine in the range of US$3–5 billion. What is not clear, however, is whether this settlement will include any privacy restrictions or oversight going forward. The settlement could mark a step toward improved technology governance, or a step backward — another page in Facebook’s playbook for staying ahead of regulating bodies.