Weighty but ill-defined terms frame the agenda at COP 20. One attends a session on “Equity and Differentiation in the Context of INDCs [Intended Nationally Determined Contributions]” and the speakers promise they will not waste time defining equity since the audience understands the term well. The lawyers in the room shift uncomfortably, and the diplomats wince, both groups knowing they could debate for days and never agree on what equity means. In law school one learns that in the old English courts of equity it was said to be measured by the conscience of the sitting Lord Chancellor, an absurdity considered no better than choosing to measure distance by the length of his foot! (J Selden, Table Talk, quoted in M B Evans and R I Jack (eds), Sources of English Legal and Constitutional History, Butterworths, Sydney, 1984, 223–224).

The UNFCCC implicitly acknowledges in its preamble the importance of equity and that it may mean different things to different parties (See UNFCCC Convention):

“The global nature of climate change calls for the widest possible cooperation by all countries and their participation in an effective and appropriate international response, in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and their social and economic conditions.”

Equity is everywhere at COP 20, demanding to be nailed down in texts and programs. Today’s blog focuses on raising a variety of equity considerations relevant to climate change:

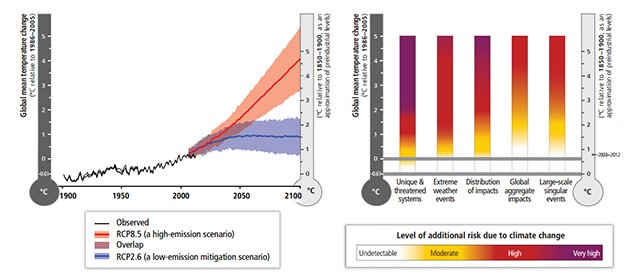

Equity in the rationing of the remaining carbon budget. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth report 2014 (PDF) confirms that if the world aims to keep temperature increase capped at 2 degrees Celsius, there is a only a limited amount of GHGs that can still be emitted into the atmosphere. How should that carbon budget be allocated? (See the Global Carbon Project).

Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report.

Since 1860, the GHG emissions have been increasing, initially in industrial England, then in Germany and the USA. By 1999 about 50% of the carbon budget had been emitted, mostly by the US and Europe, with Asia by then contributing an increasing rate. By 2014 69.9% of this carbon budget had been consumed. In the last few years, China has surpassed USA total GHG emissions. While industrial emissions are the major source of GHGs, agriculture and forest destruction account for 31%. Is there a mathematical formula or an equity principle which would help determine, in light of this historical information, current emissions and development needs, how the remaining carbon budget should be allocated?

Equity in access to energy and access to development. The developed world that created the problem of climate change now asks the developing world to forgo taking the same carbon-heavy approach that the West took in its development. The developing world asks for equity in gaining access to affordable energy for the essentials of development and modern life. Indeed today, even the developing world views access to the internet, powered by energy, as a human right. Will the developing world get access to green energy to meet its development needs?

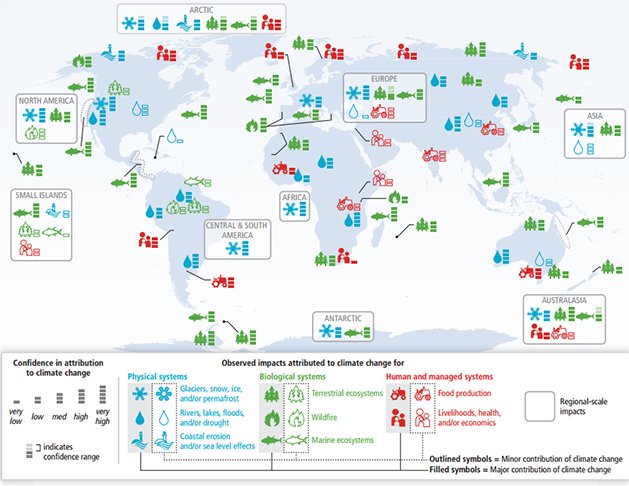

Equity in sharing the burden of the effects of climate change. If a maximum increase of 2 degrees Celsius is the global goal it is likely that the most vulnerable parts of the world will nonetheless experience devastating climate change, for example, in low-lying underdeveloped island states, and the arctic. They may have to confront the worst effects of warming oceans – melting ice, rising water levels, more severe storms, erosion of land mass, destruction of coral reefs, and other impacts on species. As well, there are agricultural areas that are vulnerable to crop-destroying drought or floods that could create serious problems of food and water insecurity. The UNFCC seems incapable of agreeing to adopt a 1.5 degree goal, which might save these first climate change victims. Therefore a profound inequity exists: harm will be felt most severely by those least responsible for causing it. What will be done by way of mitigation and adaptation to help these first victims, and who will pay for the loss and damage they suffer?

Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report.

Equitable compensation for climate change loss. The Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts is meant to enhance understanding of comprehensive risk management and the effects of climate change, foster dialogue, provide action and support including finance, technology and capacity building. With the growing number of victims of catastrophic climactic events, the Warsaw mechanism is viewed as too weak and advocates are exploring more aggressive and effective approaches to address loss and compensation. Should there be a specific state to state climate change loss dispute mechanism? Should communities or individual of one state be able to bring climate change loss claims against their government, major emitters and other states that have significantly contributed to their loss? Where could such claims be made and how could damage awards be enforced? Should there be a global catastrophic climate change risk insurance fund? If so, who should contribute to it, and in what shares?

Equitable sharing of responsibility. Within a state is everyone equally responsible for the total national emissions, or should they be attributed to the major emitters and should individuals be held responsible for what they can control by way of carbon footprint? Should there be equitable sharing of the burden of mitigation and adaptation measures? Can major emitters be held legally accountable for their contribution to climate change? Living in a carbon economy how does one equitably change the rules of the game without destroying economic value? How does a nation equitably share the burden of climate change mitigation across all its regions with their differing interests and strengths?

Equity between generations. Whatever the equities may be among today’s global population, states and corporations, all the living have more ability to improve the situation than unborn future generations. What burdens of mitigation and adaptation should current generations undertake in order to preserve equity for future generations?