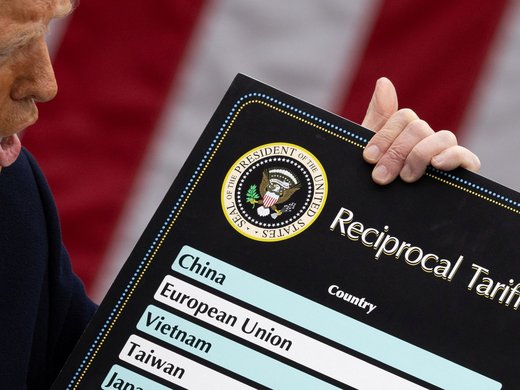

Tariffs are President Trump’s Swiss Army knife; he uses them to punish close friends like Canada as well as to force policymakers in China to further open their markets.

With these tariffs, Trump is not only devastating American alliances and global value chains, he is also undermining years of effort to bring accountability, democracy and transparency to protectionist policies.

Policymakers use protectionist tools such as tariffs, quotas and exchange controls to protect domestic firms and consumers from injurious imports.

While governments should protect their citizens from the harms caused by trade, protectionism can also cause harm. Protectionist policies can also favor some interests over the general interest and increase costs to the many at the expense of the few.

Finally, protectionism is often unaccountable, the beneficiaries of protection are not required to inform government officials how they used the relief from foreign competition.

American history, from the very beginning, is replete with attempts to make trade policy accountable. The American colonists lacked representation in the British Parliament and could not convince King George they were being unfairly taxed. Hence, in 1773, they threw tea in Boston Harbor, declaring that “taxation without representation is tyranny.”

Yet for much of American history, Congress has also been easily swayed by sectors’ demands for protection. Protectionism was so entrenched that in 1930, despite the downturn, Congress approved the Smoot Hawley tariff, which raised rates on many goods.

The Great Depression helped Americans rethink both the trade policymaking process and outcomes. In 1934, Congress authorized the Department of State to create a new bureaucracy to advise the Congress on tariffs. Firms and individuals could now present their views and independent experts could then make informed decisions.

This was a huge step forward.

In the 1940s, trade reformers went global with efforts to improve the trade policymaking process. In 1948, 23 nations committed to the first multilateral trade agreement; the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It established rules and a process regarding how and when nations could adopt measures that distort trade.

GATT rules also acknowledged that there are times governments must restrict trade to achieve legitimate and necessary domestic policy goals such as; protecting national security or public morals (the exceptions), but policymakers must do so in the least trade distorting manner possible. Thus, the GATT internationalized a more accountable process for enacting protectionism.

All this helps explain why all trade agreements today, including the GATT’s successor organization, the World Trade Organization, contain rules that require signatory governments to adopt a process rooted in the rule of law for trade policymaking. Specifically, individuals have the right to see, challenge and dispute potential trade regulations.

All of this changed in March 2018, when Trump decided to use the national security exception to enact protection on steel and aluminum. The architects of the GATT and the WTO knew the national security exceptions could easily be abused, and to limit the abuse, they required that the party adopting protection must notify the other members whose rights under the agreement must not be breached.

The Trump administration’s strategy was both confusing and opaque; it placed tariffs not only upon the biggest suppliers of steel but also upon NATO allies such as Canada and on Costa Rica, which has no army.

When Trump imposed these tariffs, he acted without consulting Congress, and he ignored the pleas of economists, business leaders and foreign governments to address steel and aluminum issues in a more constructive manner. Moreover, Trump did not reveal that his own Council of Economic Advisers had warned that these tariffs could slow economic growth. Some members of Congress have complained that Trump’s approach “upset longstanding laws.”

In sum, Trump’s approach to protectionism is not only a risk to economic stability; it is a threat to good governance. One man’s actions are a stark reminder that without an equitable and accountable process, protectionism can be a form of tyranny.

This article originally appeared in NY Daily News.