Safety drills are common practice in most schools and workplaces. Nearly everyone has gone through a fire drill — hardly a surprise, since, for many buildings, laws require them on a regular basis. But this was not always the case. Duties to conduct emergency preparedness drills evolve over time, responding to the threats of each era. In the 1950s, students crawled under their school desks to prepare for nuclear attacks; today, many states mandate drill lockdown practices for different types of threats both near and inside schools themselves. Beyond drills, various workplace laws and policies require regularized checkups and inspections to make sure essential items such as first-aid kits are well-stocked.

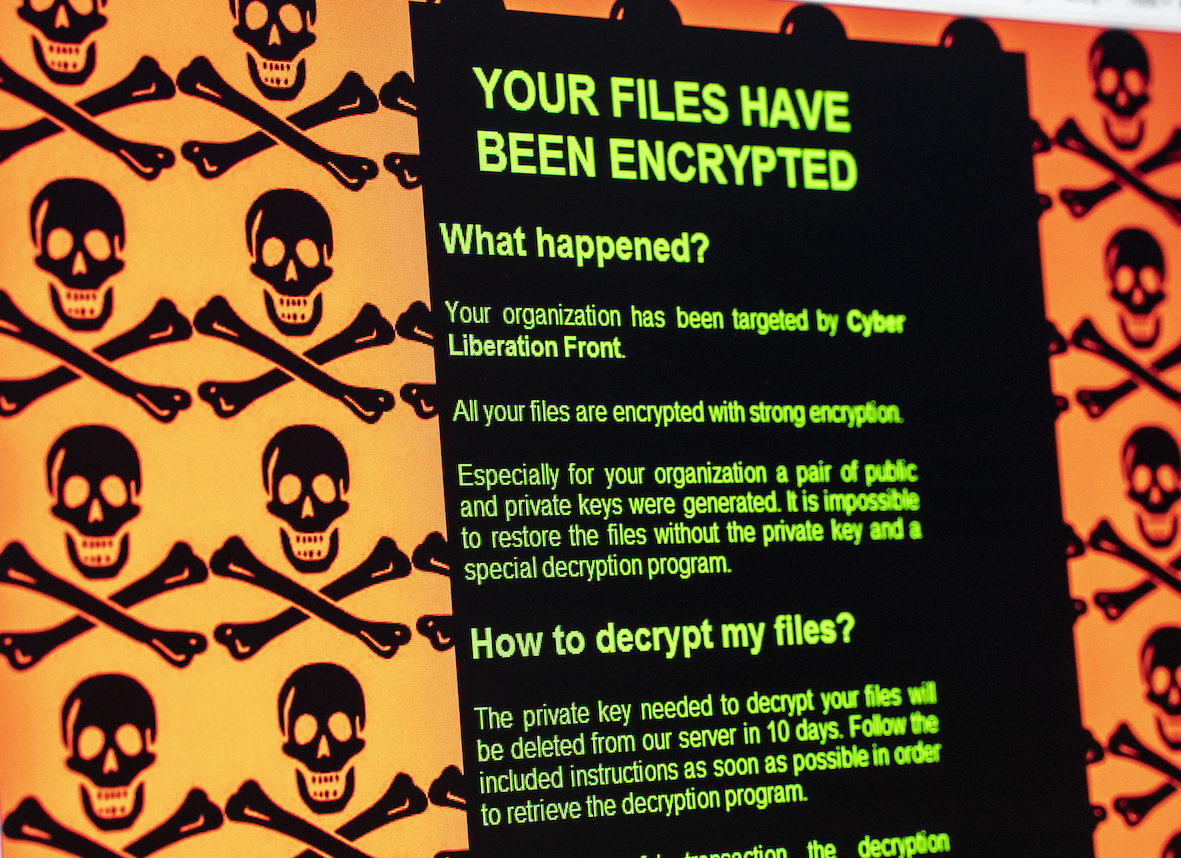

These are venerable efforts to use law and policy to counter serious threats by creating proactive duties. But some threats get no such attention. One of those is malicious cyber activity, which is identified by the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation as among the most significant risks facing the United States. Despite this grave concern, American laws tend to treat this threat retroactively, not proactively. This should be fixed.

Take the example of data breaches. Retroactively, most privacy laws require that organizations report data breaches after they occur. President Joe Biden’s administration has sought to expand these obligations. Depending on the type of data breached and the extent of the ensuing harm, an organization may be required to notify affected individuals about the breach. But apart from making people aware of their victimhood, notification rarely does much to redress harms caused. Data breach class actions have also been largely unsuccessful in delivering justice to victims.

Proactively, the law could do better. Requiring that organizations conduct malicious cyber incident simulation exercises — by, say, simulating a data breach through a mock drill exercise — would spur organizations to prepare for the worst. Last fall, a bill was introduced in the US Senate to require simulation of a partial or complete shutdown of critical infrastructure. While that bill has since stalled, simulations are something that US allies are also calling for. For example, the United Kingdom’s “National Cyber Strategy 2022” policy paper explicitly recommends them for critical national infrastructure. In Silicon Valley, simulating malicious cyber incidents is a regular part of doing business, as I learned when I practised law there. The utility of these exercises lies in making sure all actors in an organization know their respective roles during the incident response.

Most of the emergency drills known to average citizens — everything from fire drills to first-aid inspections — are due to workplace health and safety laws. These laws have proven quite adaptive. In the 1970s, they focused on physical threats like toxic materials and dangerous equipment. Over time, they expanded to include duties to address new concerns, such as harassment. Employers may grouse that they waste time and money on these efforts, but as someone who has both defended employers and also conducted neutral workplace investigations in response to these laws, I know employers are not about to flout those legal duties by failing to comply. They fear liability.

While individuals may mutter about the inconvenience of a given drill, they and their organizations undoubtedly benefit from the readiness it demands. Drills remind us that the worst can happen; in doing so, they elevate our awareness of the threat and enhance our ability to respond to it. Since such simulations require us to identify and assign responsibility within organizations — and since no one wants to be blamed for a screw-up — they strengthen due diligence and preparedness. These dynamics often prevent the worst from happening.

By imposing a requirement to simulate malicious cyber incidents, legislators could take care to impose the duty on specific kinds of organizations based on size, sector and importance. Ultimately, creating a duty for organizations to conduct malicious cyber incident simulations is a good way to implement the baseline cybersecurity principles developed by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency. Given the ongoing stalemate in the update and harmonization of privacy laws (US federal privacy remains a patchwork of laws that leave out most of the data collected by market actors), simulating malicious cyber incidents also presents a nimbler way to spur the shift toward a paradigm where responsibility for cybersecurity is spread throughout the cyber ecosystem. This way, collective vulnerability is not the result of governments’ failure to update and harmonize privacy laws.

Lastly, and most importantly, the costs of failing to act are very serious. Last year, the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack deprived several regions on the Eastern Seaboard of energy supplies and sent fuel prices skyrocketing. The notorious SolarWinds Orion Platform breach has come with significant cleanup costs. Although there were arrests in Russia of individuals allegedly associated with the Colonial Pipeline attack, there remains an aura of impunity to engaging in this type of conduct.

Rather than wait for the next malicious hack attack to paralyze the operation of any of the many pieces of critical infrastructure — hospitals, power grids, pipelines, water plants, sewage treatment facilities, airports, harbours, telecommunications networks, banks — we should act now. Creating a legal duty to actively rehearse the responses to these threats through routine simulation drills is a good way to start.