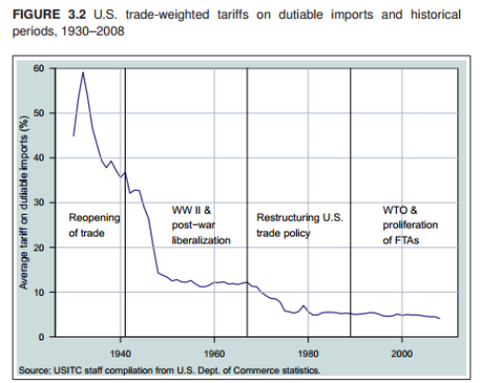

Paul Krugman has an interesting post, here, about why we shouldn’t be terribly concerned that global trade hasn’t grown as rapidly as output as it did in the past. Krugman produces a chart of U.S. trade-weighted tariffs over the past 80 years or so (below). The chart tells an interesting story of possible relevance today.

The chart reflects the enormous changes to the global trade system from the depths of the Great Depression, through post-war recovery, and the “golden age” of international growth, to today. Starting from the economic stagnation of the 1930s, U.S. trade-weighted tariffs peaked at 60%. Tariffs at such prohibitive levels (remember that an average tariff at the level implies that some tariffs were, in fact, higher still) resulted from beggar-thy-neighbour policies as country after country adopted tariffs in a misguided effort to preserve employment at home by destroying purchasing power abroad. A steep decline in average tariffs immediately after the war (which could be attributed to both tariff reductions and a recovery in trade volumes of goods with relatively lower tariff rates) was followed by a gradual decline through the 1960s and 1970s, down to rough 5% by the early 1980s. That drop in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s coincided, of course, with the successive rounds of multilateral trade liberalization conducted under the auspices of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs.

What the chart doesn’t reveal is the role of the international financial architecture, particularly the IMF, in this story. International financial stability is always a good thing — instability creates uncertainty, and uncertainty acts like a tax on economic activity, either because costs are incurred to hedge against bad outcomes or because uncertainty leads to an option value of waiting as investment and consumption is postponed. In the dark days of the Great Depression, currencies were subject to large movements: typically, steep depreciations as currencies left the dysfunctional gold standard of the inter-war years. Such moves were part of the necessary adjustment process as countries freed from the bonds of the “barbarous relic” (as Keynes referred to the gold standard) sought to stimulate growth through monetary expansion. Of course, to other countries, these exchange rate changes looked a lot like a conscious attempt to expand employment at home by exporting more and importing less. Such blatant efforts to “manipulate” currencies were therefore met by offsetting tariff increases. But higher tariffs led to retaliation and still higher tariffs. Over time, global trade was stifled by prohibitive tariffs and the widespread adoption of restrictive currency practices that rendered most currencies inconvertible. Trade flowed less on the basis of open, transparent market signals; more on the basis of opaque political agreements that led, sadly, to heightened tensions and growing suspicions.

Given this history, the prevailing view at Bretton Woods was that a clear chain of causation ran from the financial instability of the 1930s, to beggar-thy-neighbour tariff and currency practices, and to a collapse of global trade (neatly illustrated in Kindleberger’s famous “spider web” chart showing the steady, month-by-month collapse in trade volumes). The goal was to resuscitate the global economy and create an open, transparent trading system through which countries would be able to generate the foreign exchange needed to repay their obligations.

Trade was at the heart of the problem then; lowering tariff levels was a priority. No country, however, would be prepared to reduce tariffs and endure the internal restructuring that would be associated with trade liberalization if other countries didn’t likewise reduce their tariff. Nor would countries be prepared to engage in mutual trade liberalization if some were permitted to practice currency manipulation that gave them an unfair competitive advantage; in effect, exchange tariff protection for protection from an depreciated exchange rate.

These considerations account for the IMF’s role in policing exchange rate movements and current account liberalization. After decades of trade liberalization in which all the low-hanging fruit of tariff reductions have been harvested, these considerations are less significant to the IMF. Nevertheless, while its mandate is usually cast in terms of preventing international financial stability, that mandate is intertwined with the broader goals of the original international financial architecture.

The question today is: are we facing similar constraints and considerations as those which influenced the Bretton Woods architects? The ongoing debate of currency manipulation and the high debt burdens facing many countries (especially those in the euro zone) form an interesting nexus for further consideration.