The students in my 2017 graduate corruption class spent 14 weeks struggling to understand the many variants of corruption. They come to class recognizing that corruption is endemic. They know that every country — even the best governed — has some degree of corruption.

But they didn’t know much about the direct and indirect effects of corruption or its relationship to trust. While they understand that corruption can undermine economic growth and political stability; they didn’t realize that it can also, lead to efficiency losses, impede access to resources, such as credit or public health, reduce governance effectiveness, and erode democracy.

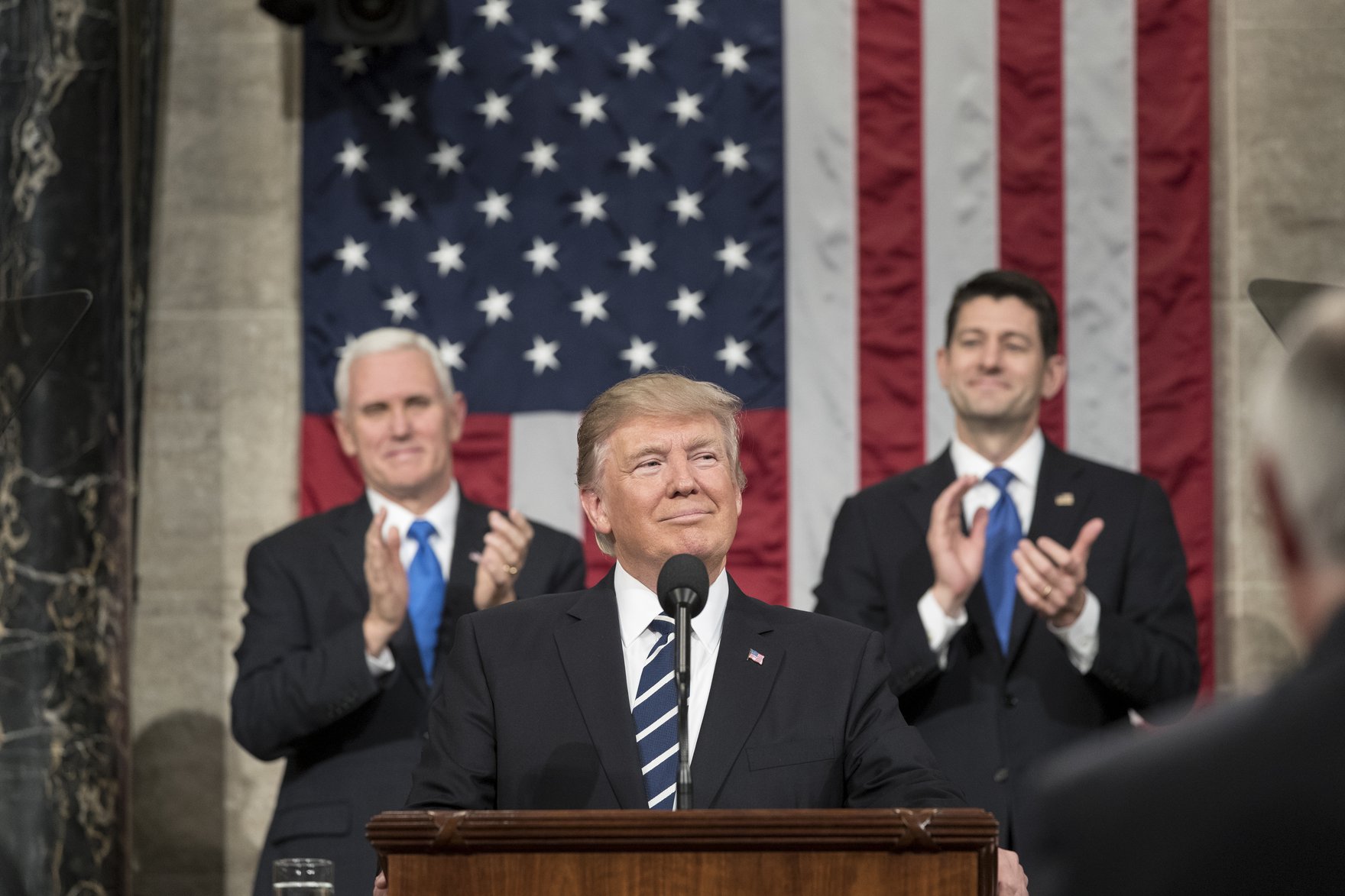

However, this semester my students saw a case study play out live as Congress debated the Tax Cuts and Job Act of 2017.

My students recognized that because, corruption is opaque, it can’t be measured. Hence, we also study the strength of anticorruption counterweights, such as a free press, a system of checks and balances, auditors, accountability organizations or budgetary and spending regulations. etc. … that help citizens hold their government to account. Because anticorruption counterweights are visible, analysts can measure how effective they are.

Next, we examine the role of trust, which we can measure through public opinion surveys. When leaders act in a corrupt manner, they are abusing entrusted authority for private gain. Without trust among citizens of diverse means and education, governments cannot solve problems.

Moreover, societies with low levels of trust tend to have higher (or increasing) rates of economic inequality, ineffective governments, less optimism, closed markets and lower growth. And perhaps most problematically, once trust has been lost or damaged, it is hard to revive it.

Countries with strong and abundant anticorruption counterweights also tend to have higher levels of trust. But the United States doesn’t quite fit this neat model.

The United States has strong anticorruption counterweights, such as an even-handed judiciary, strong accounting institutions, a free press, checks on executive and legislative power, and right-to-know laws, to name a few.

Yet the United States also has extremely low levels of trust. Only 18 per cent of Americans polled by Pew in 2017 said they could trust the government in Washington to do what is right. A slim 3 per cent thought that they could trust the government “just about always,” and 15 per cent felt that they could trust the government “most of the time.”

Deep inside this anomaly of a high-counterweights-low-trust system, the tax bill provides evidence of a system rife with corruption. The United States has high levels of grand corruption because political financing is considered free speech, allowing corporations and the rich to have significant influence over politics. Since the Citizens United decision by the Supreme Court, money has flowed directly to candidates who then feel they must respond to their donors’ needs.

The effects of the Citizens United decision became clear with final version of the Tax Cuts and Job Act of 2017. The bill was developed by Republican members who refused to co-operate with Democrats; they held no hearings on the specific language of the bill. Moreover, Republicans in Congress admitted that they were making these changes to the tax code to satisfy their major donors.

However, while Republicans argued that the plan would boost growth and create jobs, economists and the American public disagreed. The Joint Committee on Taxation found that the bill would stimulate growth by less than 0.08 per cent a year. The bulk of those polled saw the legislation not as a tax reform bill, but payback to donors who are often America’s wealthiest citizens and corporations. Overall, 71 per cent of voters say the plan will raise their taxes.

If the bill becomes law, it could have many negative consequences for the United States. The architects of the bill paid little attention to its potential effects upon investment, infrastructure, education and productivity. The plan would increase the deficit and make it harder to invest in the goods and public services that increase growth (scientific and applied research, health care, education and infrastructure).

Finally, this bill will further exacerbate income inequality in the United States. Jason Furman, the former chair of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, said that instead of stimulating long-term growth, the tax plan “changes how the economic pie is shared.” And last week, The New York Times concluded that the tax plan’s biggest cuts could be in living standards.

What kind of leaders would pursue a tax bill that worsens growth and inequality? Leaders who don’t care about being accountable to voters. The same members of Congress ignore public opinion on gun control and health care.

Given this disconnect, my students and I likely share the conclusion that the United States, that former city on a hill, has become a kakistoctracy, a government by the worst people.

This article first appeared in The Toronto Star.