Last week ended with general confusion about the seemingly perilous status of Greek debt negotiations. Paul Krugman had an interesting post, here, earlier in the week in which he asked if the impasse between Greece and its creditors reflects a "bring it on" mentality reminiscent of the rush to war in August 1914.

Populations whipped up by war fever thought only of the glories of war and not the gore and suffering of the battlefield. It would be a short, decisive campaign they thought. The problem is that both sides held that view; too few shared Lord Grey’s melancholic assessment: “The lamps are going out all over Europe,” he sighed, watching the London crowds cheer the declaration of war, “we shall not see them again in our lifetime.”

The rush to war in August 1914 is an example of what the historian Barbara Tuchman referred to as the March of Folly. Is the current confusion another example?

At issue in the impasse between Greece and the creditor institutions is the role of “internal adjustment” in a monetary union. This isn’t the first time this problem has come to the fore, see here. Krugman neatly sums up the economics of the situation: Greece can't run a primary deficit (before interest payments) without compliant creditors and it won’t run a large primary surplus; so, a possible outcome of the bargaining game would be to agree to a modest surplus. This strikes me as imminently sensible, particularly if there are risks to both sides of failure.

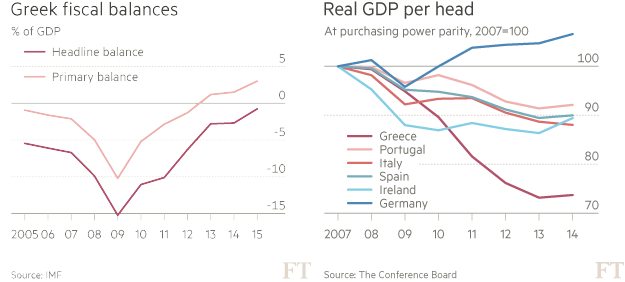

In this respect, those confidently predicting minimal impact of a Greek default and possible exit from the Eurozone had better not be the same people that supported extraordinary IMF support for Greece a few years back on the basis of the systemic contagion exemption — the argument that the Fund couldn’t allow Greece to default because of the repercussions that would have on others. In the event, the Fund provided an extremely large financing package, together with the EU and the ECB, while Greece gamely undertook adjustment. Martin Wolf, writing in the Financial Times, has a couple of graphs that show the results:

From a primary deficit of 10 percent in 2009, Greece has moved to a primary surplus of about 3 percent — a net swing of 13 percentage points. It can’t be said that Greece hasn’t adjusted. Real GDP per capita, meanwhile, has fallen far more than other highly indebted Eurozone members; so it can’t be said that Greek politicians have been unwilling to inflict pain on their own populations.

The thing is, though, if those claiming that Grexit doesn’t pose a threat to the rest of the Eurozone or the global economy are the same people that a few years ago pushed the IMF to provide exceptional access on the grounds of systemic contagion, don’t they have some explaining to do? Of course, they could say that the threat of contagion then was the potential consequences of a Greek default on Eurozone banks, which have used the intervening time to build up reserves. But that begs the question: for whom was the bailout intended — Greece or the taxpayers of other Eurozone countries that would have likely had to have intervened to rescue their banks?

Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly consists of the pursuit of policy actions that are contrary to self-interest by a group, rather than an individual, against advice available at the time. Only time will tell if the two protagonists join the ranks of those rushing off to join the march.

Regardless, the confusion that reigns adds to the fog of doubt that impairs global growth in the New Age of Uncertainty.