Since the subject was put on the international policy agenda by Brazil’s finance minister almost three years ago, much of the talk about currency wars has been phoney. That is to say, contrary to reporting from the putative battlefield, the use of quantitative easing by key advanced country central banks, which some claimed was the opening salvo in the currency wars, was not designed to bring about a depreciation of their currencies.

Rather, these extraordinary policy measures reflect economies that were (and still are) struggling to make up output and employment levels lost in the global financial crisis, dysfunctional financial markets, and the zero lower bound to which conventional monetary policy responses by advanced country central banks had driven nominal interest rates. In the face of large output gaps, low inflation and symmetrical inflation targeting (under which the central banks responds equally to undershooting the inflation target as overshooting), quantitative easing is not only fully justified but entirely consistent with international commitments — sustained sub-par growth in these economies would not help the global economy.

Of course, one consequence of extraordinary monetary measures is currency depreciation. And, if you are on the other side of the exchange rate — as dynamic emerging economies have been — that means an appreciation of your currency. Significant currency appreciation can erode the competitiveness of your exports and reduce current account surpluses (increase deficits). This is unwelcome in countries that have relied on an export-led growth model. But countries that have experienced a significant appreciation should note that the strength of their currencies reflects their relative economic strength. Exchange rate adjustments are merely the means by which global supply and demand is balanced.

As the International Monetary Fund has warned in its recent World Economic Outlook, efforts to resist nominal exchange rate adjustments will merely result in higher inflation and/or capital flows that fuel asset price bubbles and further stoke inflationary fires. Prudential capital controls can help reduce such capital in-flows. But a defensive strategy of controls and only capital controls is likely to be a losing gambit if the aim is prevent exchange rate appreciation. Controls will, eventually, become porous, while the Fed’s ability to create liquidity far exceeds the capacity of controls to prevent that liquidity from seeping into and distorting domestic financial systems. (As the old adage from Wall Street goes, “don’t fight the Fed.”) In the end, countries that seek to resist currency and inflation will end up with both — as higher inflation leads to a real, or inflation-adjusted, currency appreciation. Add to that a risk of asset price bubbles or real estate speculation, and learning to live with some nominal appreciation — if not too rapid and overly disruptive — starts looking more attractive.

This is where concerns of possible currency wars have begun to gain traction. The simple fact is goods price adjust slowly while asset prices (including exchange rates — the relative price of two currencies) adjust much more quickly; indeed, asset prices can “jump” to new equilibrium virtually overnight. The upshot is that, because of these different speeds of adjustment, real exchange rates and also measures of competitiveness can move very quickly, “over-shooting” long-run equilibrium levels. And since real exchange rates affect “real” magnitudes — output, employment — such large movements can be the source of dislocation and disorder. Governments typically don’t get re-elected in this environment. As a result, there are strong incentives for governments to prevent such disruptive adjustments.

These efforts could be justified if the aim is to smooth the speed of adjustment so as to allow domestic firms time to adjust to the incipient real appreciation and not prevent or block the underlying real appreciation associated with divergent cyclical positions. But what if, instead, the country is intent on avoiding the “hot potato” of international adjustment in order to sustain an export-led growth strategy or continue reserve accumulation, so as to avoid possible future financial crises? Then concerns of currency manipulation designed to gain or unfairly preserve competitive advantage come to the fore.

In these circumstances, there is a risk that protectionism could once again rear its ugly head. We have been exceedingly fortunate that we have avoided a return to trade wars, thanks to the G20 standstill agreement on protectionism and the bonds of global cooperation woven by the collective efforts of the institutions in the international architecture. But there are signs that those bonds could be tested by the threat of currency wars.

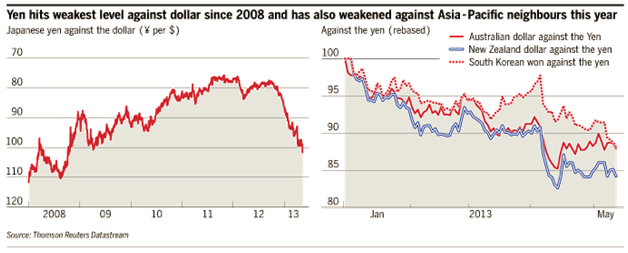

In just the past few days we have seen worrying developments. Since the Bank of Japan has embraced Abenomics and begun to put its balance sheet where its mouth is in efforts to generate higher inflation, the yen has slid against the dollar (see chart from the Financial Times). Countries that largely escaped the worst of the financial crisis and have fared reasonably well (and thus are close to full employment), meanwhile, have eased monetary policy to avoid further appreciation of their currencies, perhaps thinking that it is better to temporize with the uncertain risk of possible higher inflation than suffer from the known burdens of further currency appreciation. This group includes Australia, New Zealand and Korea.

This assessment may be somewhat unfair: given the long and variable lags associated with monetary policy, central banks have to respond to where they think the economy will be several quarters in the future, rather than where it is now; recent actions may therefore reflect growing unease about growth prospects. Nevertheless, if a growing number of countries that are at or near full employment resist exchange rate adjustment, what is a country still struggling to make up output and employment at the zero lower bound and with possibly dysfunctional financial markets to do? The answer, unfortunately, is to threaten to let loose the dogs of protectionism. Calls for Europe to erect trade barriers against “unfair” Chinese competition are likely to increase in number and intensity, particularly after today’s release of Q1 growth estimates, which can only be described as dreadful. Thankfully, that has not been the response, but the longer that unemployment remains too high, and at Great Depression levels in some countries, the greater the risk.

In other words, it may be time to get real with regard to the threat of currency wars.