Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveller, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim

Because it was grassy and wanted wear,

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken

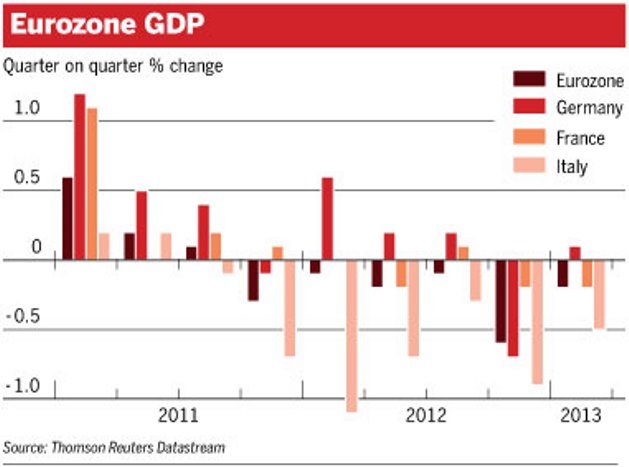

The European Union released its estimates for first quarter growth this week. As noted previously, the results were, in a word, “dreadful.” The chart below from the Financial Times, here, sums up the situation. Even the most ardent supporter of the European project no doubt finds it difficult to put a positive spin on the numbers. Sadly, the prognosis is more of the same.

Almost a year ago, G20 leaders met at Los Cabos, Mexico amid widespread concern (crisis-induced panic?) regarding the prospects of a possible Greek exit from the euro zone. Under the watchful eye of their G20 colleagues, Europe’s leaders agreed to “support the intention to consider concrete steps towards a more integrated financial architecture, encompassing banking supervision, resolution and recapitalization, and deposit insurance.” In other words, to work toward measures to stem the crisis that was threatening the financial systems of euro zone members and posed a clear and present danger to the global economy, writ large. First and foremost was agreement on the need to build an effective banking union.

The show of unity that euro zone leaders displayed in Los Cabos conveyed the impression that they understood the gravity of the situation and were prepared, possibly, to grasp the nettle and fill the governance gaps in their joint project; yet, what restored calm to European financial markets was not the pronouncements of leaders at Los Cabos, but the determination of Mario Draghi (President of the European Central Bank) to “do whatever it takes” to preserve the euro. His commitment to provide liquidity to markets halted last summer’s panicked bank-run flight from euro-denominated assets and euro zone banking systems into relative calm.

This episode nicely illustrates the unique power of how the judicious use of monetary policy can affect expectations and thereby shift the economy from one outcome to another. It is, in other words, a social coordination mechanism that supports “good” equilibria and avoids “bad” outcomes. But, make no mistake, Draghi did not, and monetary policy measures alone could not, address the fundamental governance failures in the euro zone.

In this respect, the euro land members face two options if they want to continue with the project of European monetary union. The first option is to continue down the road of “internal devaluation” and structural reforms that will, eventually, restore full employment as real wages in the periphery adjust downward to compensate for reduced levels of productivity. That is the well-trodden path of the past several years; it entails continued high unemployment — at Great Depression levels in some countries — and strains the social and political fabric of countries making the adjustment.

The second option is to create the institutions needed to support a monetary union for countries that do not satisfy the conditions of an optimal currency area. This will take considerable time. It is the road less travelled. And, frankly, it is the more difficult path because it requires political institution building and the delegation of national sovereignty.

This is the crux of the matter: a decade ago, member states might have been prepared to cede national sovereignty to euro land institutions in order to reap the benefits that monetary union would bring. (No state voluntarily gives up sovereignty, but “pooling” sovereignty with others might be attractive if the prospective gains are big enough.) The decision rule is simple: “stay” if the discounted present value of benefits from remaining in the euro zone exceed the discounted present value of the costs; otherwise “exit.”

The rule is simple, but the considerations involved are vastly more complex. This no doubt accounts for the hesitation and false steps that euro members have shown with respect to building euro area institutions. This week German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble cast doubt on the legality of plans for an EU-wide bank resolution and rescue agency. In doing so, he is defending the interests of German taxpayers, who would likely bear the brunt of the costs of future bank failures.

For the immediate future, therefore, the road not taken will likely remain the road not taken. In the meantime, markets may test Mario Draghi’s commitment, which, it could be argued, was given in exchange for institutional reforms; Europe will likely remain weight on the global economy in the New Age of Uncertainty.