After the 2008 Global Crisis, there has been progress towards a system-wide regulatory architecture that includes a national macroprudential authority. This column describes a ‘capacity indicator’ that measures the state of macroprudential policies worldwide, including the features policymakers believe constitute a successful macroprudential policy regime. Eventually this index may be used to establish whether these macroprudential policy innovations have been successful.

A considerable research effort is being devoted to financial stability and, more precisely, macroprudential policy. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has championed macroprudential regulation for more than a decade (Borio and White 2004), but the term dates from the 1970s (Barwell 2013). As early as 2000, then-BIS general manager, Sir Andrew Crockett, advocated that:

“Strengthening the macro-prudential orientation…is important because of the costs and nature of financial instability. The main costs take the form of output losses. The nature of the processes generating instability puts a premium on a macro-prudential conception of economic behaviour” (Crockett 2000).

Macroprudential regulation has gained traction since the 2008 Global Crisis and is now considered to be a necessary component of a financial system stability framework (Tucker 2016). The Financial Stability Board (FSB) now is helping to create guidelines for best practice in the implementation of a macroprudential framework.

Lombardi and Schembri (forthcoming) highlight the evolving state of financial stability frameworks in advanced economies, emphasising the role of central banks. They argue that central banks are well-positioned to identify, assess, and communicate financial vulnerabilities and risks because of their system-wide macro-financial perspective, their analytical capacity, and their independent status. They also emphasise that the agencies at national and international level with important roles in promoting financial stability need to possess clear mandates, and they need to work together to develop minimum global regulatory standards for financial stability and to monitor emerging vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, there is still little agreement on what a comprehensive and effective macroprudential policy framework would be.

We have identified more than 30 key empirical elements of the current state of macroprudential policy for 46 economies (Lombardi and Siklos 2016). We have also translated them into a ‘capacity index’ that scores policy regimes. Our index compares apparent factors, such as the size and scope of a policy coordination body, the central bank’s involvement in it, and the arrangements for delegation of authorities. But it also compares each jurisdiction’s framework with the recommendations of the FSB and the Group of Twenty (G20), a crucial benchmark which previous research has not considered.

While existing indicators of central bank independence are either based on an interpretation of central bank laws (de jure) or are derived from their actual performance (de facto), our indicator combines both. We do this because only some of the characteristics of macroprudential frameworks are clearly observable (for example, the degree to which central bankers publicly discuss their views on financial stability) while others are based on expectations that the international community will adhere to (agreed-upon regulatory principles and rules).

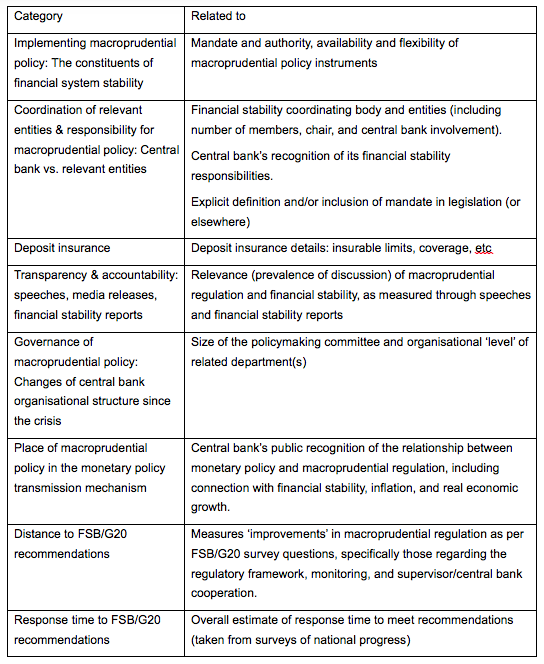

Our indicator has eight distinct features, as shown in Table 1. They summarise the following areas of macroprudential regulation:

- The availability of macroprudential policy instruments

- The definition and recognition of a financial stability mandate

- The allocation of institutional responsibilities between the central bank and other agencies

Table 1 Components of the macroprudential capacity index

Source: Lombardi and Siklos (2016).

We have not, however, evaluated how effective the framework is, or is likely to be. This will only be possible after the frameworks have been in place for longer (see also Masciandaro and Volpicella 2016).

To our best knowledge, only two studies have attempted to quantify macroprudential policy frameworks in a similar way. Lim et al. (2013) ranked institutional setups on an ordinal scale, based on the respective de jure roles of central banks and governments in macroprudential regulation. The authors concluded that small open economies tend to have a more integrated approach, with the central bank ordinarily the competent authority, while more complex economies leave a larger role for the government. Cerutti et al. (2015) created a time series indicator of the effectiveness of known macroprudential tools in dampening credit cycles for 119 countries from 2000 to 2013, and found that macroprudential tools are effective at reducing credit growth. However, prior to the Global Crisis, it is questionable whether the tools available were intended to deal with macroprudential concerns as they are understood today.

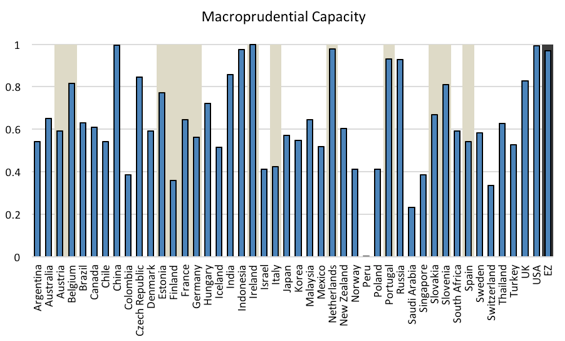

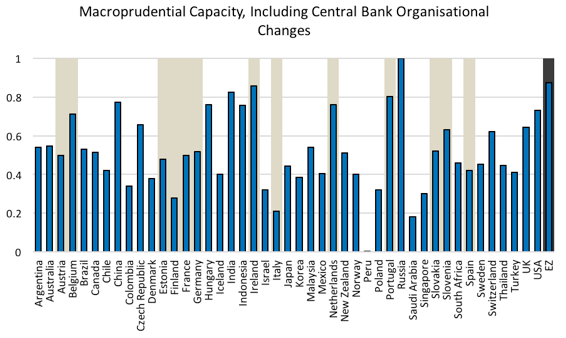

Scores for individual economies

The bar chart in Figure 1 shows two variants of our macroprudential capacity indicator. The only difference between the top and bottom figures is the inclusion of changes to the organisational features of central banks that are related to financial stability. Specifically, the index values shown in the lower graph have been extended to reflect changes in the departmental organisation of central banks since 2011 that are related to financial stability, such as the creation of new departments or elevation of existing ones. (We chose 2011 because this represents the year the BIS surveyed its membership to obtain organisational charts.)

Overall, a higher index value corresponds to a perceived more resilient framework for managing the risks of financial instability. To ensure comparability, the indicator shown has been normalised so that the values range between 0 and 1. Note that different weighting schemes made little difference to the rank of index scores. For a more detailed breakdown of the features of the indicator, as well as each economy’s category-specific sub-scores, see Lombardi and Siklos (2016).

Figure 1 Macroprudential capacity index: Normalised values

Note: The data have been normalised to range between 0 and 1. The shaded areas identify countries that belong to the Eurozone.

Figure 1 aggregates scores across 30 elements, and is therefore a simplified illustration of a lot of information. Nevertheless, we can draw some notable conclusions:

- Based on a score that aggregates all of the characteristics that we have identified as components of macroprudential frameworks, the major central banks of the EU and the US all scored highly.

- Once we incorporated governance structures some differences emerged. These differences reflect the debate over how much responsibility the central bank should take for macroprudential policies.

- More generally, we see that economies hit harder by the Global Crisis scored higher, reflecting a larger appetite for addressing financial instability. This is likely to have been driven by more pressure being put on politicians to take action to address past regulatory weaknesses and establish mechanisms to prevent another major financial crisis (Lombardi and Moschella 2016). Ireland, as well as many of the Eurozone economies, are examples of this. EU member countries have increased the burden of macroprudential policies on the European Central Bank as well as boosting the EU’s oversight role in these areas. The US, the UK and the EU all rank highly, whereas economies with financial systems that were relatively unscathed by the Global Crisis – such as Australia, Canada, India, and Brazil – display lower scores for the subsequent reinforcement of their macroprudential frameworks.

It would be useful to provide a rigorous empirical assessment of whether frameworks for deploying macroprudential instruments reduced the incidence of financial instability. In most instances any framework has been adopted recently, so this is challenging.

In a series of simple cross-sectional regressions, the only financial stability-related indicator that was consistently statistically significant was the relationship between our macroprudential capacity indicator and credit growth. Where credit growth was rising, this was accompanied by a macroprudential regulatory framework that has more capacity to deal with potential economic consequences.

Financial and economic systems are complex, highly interconnected, prone to instability, and can produce shocks through policy weaknesses. For these reasons, we cannot know how resilient modern frameworks will be until the global financial system experiences another large financial shock. Nevertheless, it is also worth highlighting that US, the UK, and the EU (specifically, the Eurozone) – arguably the economies most directly impacted by the Global Crisis – have put in place macroprudential regimes closest to the desires of the FSB/G20.

This index captures developments and policy initiatives in what we, and previous research, believe is the right direction. It would be, though, just one element of a more coherent collection of consistently developed and consistently updated resilience-related indicators. Before the next shock we can hope that existing regimes develop in such a way that they enhance the durability and flexibility of the current policy architecture.

References

Barwell, R (2013). Macroprudential Policy, Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Borio, C and W White (2004). “Whither Monetary and Financial Stability? The Implications of Evolving Policy Regimes,” Proceedings – Economic Policy Symposium – Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 131-211.

Cerutti, E, S Claessens and L Laeven (2015). “The Use and Effectiveness of Macroprudential Policies: New Evidence,” IMF working paper 15/61, March.

Crockett, A (2000). “Marrying the Micro- and Macro-prudential Dimensions of Financial Stability,” speech before the 11th International Conference on Banking Supervision, Basel, September 20-21.

Lim, C H, I Krznar, F Lipinsky, A Otani and X Wu (2013). “The Macroprudential Framework; Policy Responsiveness, and Institutional Arrangements,” IMF Working Papers 13/166, International Monetary Fund.

Lombardi, D and M Moschella (2016). “The symbolic politics of delegation: macroprudential policy and independent regulatory authorities,” New Political Economy, 23 June, pp. 1-17.

Lombardi, D, and L Schembri (2016). “Reinventing the Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability,” Bank of Canada Review, forthcoming on November 19, 2016.

Lombardi, D and P L Siklos (2016). “Benchmarking Macroprudential Policies: An Initial Assessment,” Journal of Financial Stability 27, pp. 35-49.

Masciandaro, D and A Volpicella (2016). “Macroprudential Governance and Central Banks: Facts and Drivers,” Journal of International Money and Finance 61, pp. 101-119.

Tucker, P (2016). “The Design and Governance of Financial Stability Regimes: A Common-resource Problem that Challenges Technical Know-How, Democratic Accountability and International Coordination”, CIGI Essays on International Finance, 3, Centre for International Governance Innovation.