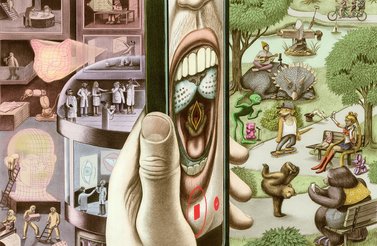

Banning digital platforms may be a futile and desperate attempt by nation-states to regain control over their digital domains. However, the symbolism of these actions is more important than their feasibility. While such efforts are arguably impossible from a technical perspective, they provide fuel for broader trade disputes, enable all sorts of domestic political posturing, and encourage the concept of national digital sovereignty.

Given the wild popularity of social media, threatening to ban platforms almost guarantees a public outcry. Similarly, these platforms generate massive amounts of revenue and lucrative profits that would motivate the government of the country that hosts them to defend their market positions in the global economy.

In this context, bans are most useful as threats, as theoretical actions but not concrete policy. Still, the threat of banning seems to be rising in popularity at exactly the moment that such bans are no longer (technically) possible or plausible.

Until recently, platform bans were a policy tool used temporarily by authoritarian regimes facing protests or upheaval. These measures were seen as a necessary part of re-establishing order and control. Their effectiveness, however, was limited and time-dependent — the longer a ban went on, the more new ways people found to circumvent them. These bans rarely last long, because the inability of the regime to enforce them undercuts the credibility and effectiveness of the government overall.

Despite the relative futility of technology bans, a government may still entertain the notion of banning a platform, especially when that platform is operated from a country regarded as a rival or opponent. The rhetoric of calling for the ban may be the point, rather than the ban itself.

Until recently, platform bans were a policy tool used temporarily by authoritarian regimes facing protests or upheaval.

The seeds of the current discourse around banning (the same discourse that seems to be making the rounds in Western democratic countries) can be found in the ongoing debate over the ban of Huawei telecommunications equipment.

While Huawei isn’t a digital platform, banning the use of its products seems equally problematic and contradictory. Most people do not understand why telecom equipment would be a national security issue, let alone how popular social media platforms would be a geopolitical concern. As a result, calls for bans are not only technically futile but could potentially alienate users of these platforms from their governments and policy makers.

That risk of alienating the populace is why it has been so important for proponents of bans to justify or tie their actions to other policies, whether trade, economics, national security, culture or privacy. In connecting the proposed ban to a larger issue, they avoid discussion as to whether a ban is actually possible.

For example, in democratic countries, the internet is structured as it was originally designed: decentralized and difficult to control. In this context, the potential bottleneck or control point is the app stores controlled by Google and Apple, which the government can order to remove a banned app or platform from their digital store shelves. (Of course, that ban can’t stop people from using virtual private network software to change their Internet Protocol address to an unlocked region, so that the app store will let them install the banned app or platform.)

This is exactly what the US government was proposing to do with TikTok and WeChat: ban them from app stores, on the grounds that they were a threat to national security. However, as many have detailed, such a ban would not prevent existing users from still using the app. And, although it would be difficult for new users to join, it would not be impossible.

In the case of TikTok, the ban threat also served other purposes — primarily, it was fodder for an election campaign that is working to illustrate that current President Donald Trump is standing up to China and protecting US economic and industrial interests from further encroachment by Chinese companies.

That risk of alienating the populace is why it has been so important for proponents of bans to justify or tie their actions to other policies.

For example, US-based Facebook is a dominant global player in social media and messaging. TikTok and WeChat pose formidable competitive threats, especially in the US domestic market. While a ban would be clearly protectionist, forcing TikTok to partner with US companies still helps to protect the US (digital) economy overall.

The legality of such moves remains in question, with the TikTok and WeChat bans both being paused by an injunction; the TikTok deal (which would see US companies partner with the company) has not actually closed yet.

Meanwhile, India has banned 118 Chinese apps, including TikTok, which was hugely popular in India. As with other bans, this was not as much about the apps as it was about deteriorating political relations and ongoing border disputes. However, it also served the secondary purpose of removing a platform that enabled growing dissent and criticism of the Indian government. Making it difficult to use TikTok and encouraging use of domestic apps helps the government in myriad ways.

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte is ruminating about banning Facebook in response to the platform’s banning of bots that supported his policies. His rise to power was enabled in part by his use of the platform as a mobilizing tool and megaphone for his politics. The relationship he has with Facebook is souring, not so much due to dissent but because he feels the company is limiting his ability to use it as he sees fit.

In both of these cases, the proposed or actual bans are mostly symbolic, and serve larger political agendas and priorities.

However, in Australia, the situation is flipped: it was not the government proposing a ban, but Facebook and Google. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) had proposed charging the platforms for using and sharing news produced by the Australian news industry as a means of supporting local journalism. In response, Facebook and Google threatened to ban users from posting or sharing news on their platforms — seemingly willing to cut off their nose to spite their face. Symbolic or not, this threat seemed to have been successful, as the ACCC is modifying its proposed legislation in response to input from the digital giants.

Facebook has made a similar threat to the European Union, ludicrously suggesting that it will pull out of Europe if disputes over the flow of traffic between Europe and the United States are not resolved.

One might take these developments as a clear sign that the rhetoric around platform bans has become meaningless. It’s one thing for a democratic government to threaten such a ban; it’s another thing altogether when these platforms start acting as if they will ban themselves.

The problem with concerns or laments over the rise of a “splinternet” (that is, an internet increasingly split into regional or national networks) is that they falsely assume that national governments control their domestic internets. While this may be marginally true in some authoritarian regimes, even then it is the activity of users that determines the direction and form of the network of networks — not governments.

Instead, what we’re seeing is the sputtering of nation-states who are increasingly being eclipsed by networks and the platforms that enable them. The United States cannot stop the rise of TikTok, nor can China. Similarly, the United States played little role in the rise of Facebook, and with each passing day, its ability to influence the direction and governance of the platform diminishes.

Rather than focus on, or give credence to, bans that don’t work, we should instead be focusing on governance models and regulatory frameworks that both acknowledge the relative autonomy of networks and recognize the need to understand and harness them responsibly.