Jeffrey Sachs has a piece in the Financial Times on the level (or perhaps nadir is the right word) to which the economic policy debate in the United States has descended. His argument is that Republican defenders of the free-market faith and the Democratic Party’s chief flag bearer, Paul Krugman, are equally confused, wrong or misguided.

He is half right.

Professor Sachs’ indictment of Krugman is curious:

"In Krugman’s simplified Keynesian worldview, there are no structural challenges, only shortfalls in aggregate demand. There is no public debt problem. There is no global competitiveness challenge, since 'competitiveness' is a myth when applied to national economies. Fiscal multipliers are predictable, timeless, persistent, and large. All growth reversals can be solved through larger deficits. Politicians can be trusted to design short-term stimulus spending programmes of hundreds of billions of dollars. Tax cuts are about as good as increases in government spending, and short-term boosts in spending are about as good as long-term public investments. Not one of these conclusions stands scrutiny."

Far be it for me to defend Paul Krugman, but reading through this list of charges led me to ponder if Professor Sachs has actually followed Krugman’s work over the years. Surely, you say, he must be aware of Krugman’s blog. But, taking Sachs’ article at face value, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that he is not. Otherwise, he would know that his charges are spurious and that Krugman’s policy prescriptions are based on an analytical model that admits the possibility of potential coordination failures that create protracted periods of economic stagnation; and while no model can ever be proven “right,” the Keynes-Krugman analysis has certainly fared much, much better than competing views of what caused the crisis and what ails the global economy.

Brad DeLong reviews the weaknesses of Sachs’ indictment, here. I want to focus on what I suspect is the "smoking gun" of the prosecution’s case:

"In Krugman’s simplified Keynesian worldview, there are no structural challenges, only shortfalls in aggregate demand. There is no public debt problem."

It is not clear what this statement is intended to convey. Is it meant to imply that Keynes’ policy prescriptions only apply at low levels of public debt? Or is the point that Keynes developed his theory at a time of low levels of public debt, so that it applied then but not now? Perhaps Professor Sachs is saying Keynesian analysis is just flat out dead wrong, regardless of the level of public debt.

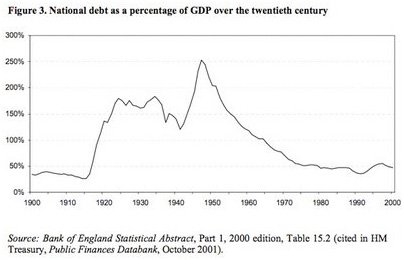

In any event, he might want to look at the U.K.’s public debt level when Keynes was writing The General Theory:

Yes, you are reading the chart correctly: U.K. national debt as a percentage of GDP was much higher in the 1930s than at any point in the last 50 years; that includes a post-crisis uptick (not shown) that raises the percentage to roughly, say, its level in the late 1960s.

Professor Sachs is a learned economist, with several significant contributions to field. It is implausible to assume that he is unfamiliar with the corpus of Krugman’s work, the insights of Keynesian analysis, or the economic history of the Great Depression. Moreover, surely he understands that it will be immeasurably harder to mobilize the resources — not to mention the political will — needed to address the fundamental challenges he identifies if growth is not restored to the global economy.

So, what is going on here? Could this be a case of Freudian projection? After all, one of Sachs’ possible explanations for the errors of others is:

"… the world is noisy and overloaded with media messaging. Getting heard seems to require a short, sharp and exaggerated idea endlessly repeated: economics as a media brand."