Prior to President Obama’s announcement of proposed new rules on coal fired power plants, news that the loss of the Thwaites Glacier in western Antarctica appears “unstoppable” created a wave of interest in the blogosphere, see Financial Times for the article. Moreover, it raises a number of interesting questions regarding climate change and international governance. Most important, in my view, is the issue of tipping points — that is to say, thresholds beyond which the relationship between one variable and another variable changes in some fundamental way. The worry is that, as greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, a threshold will be crossed that triggers large, discontinuous changes in the environment.

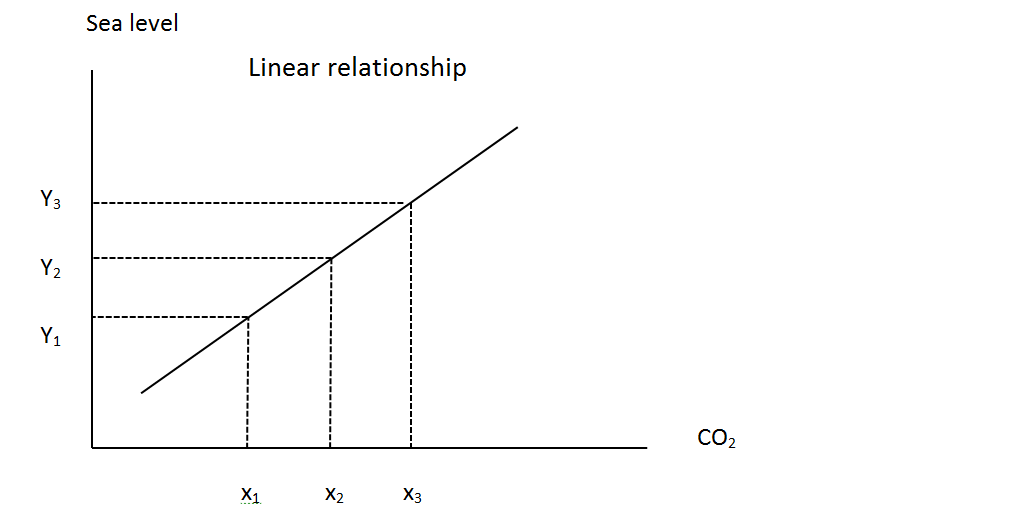

To think about these effects, consider different relationships between CO2 levels and sea level. A linear relationship is one in which a given increase in CO2 causes a given increase in sea level:

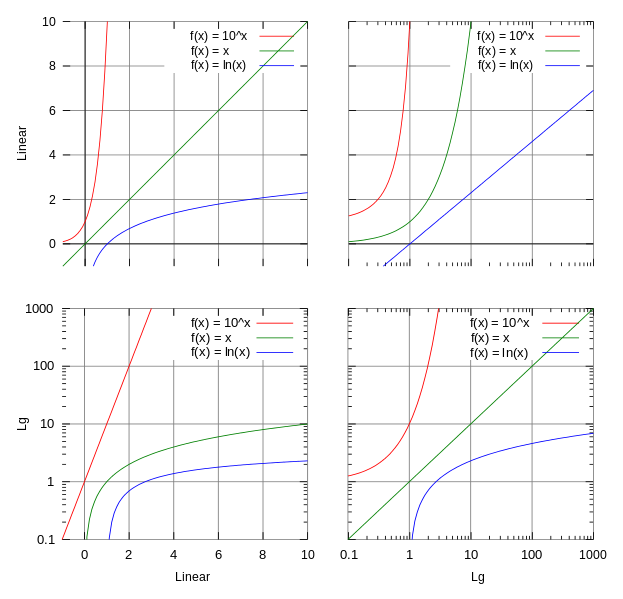

Equal changes in CO2 levels generate equal changes in sea level. Needless to say, this depiction of the relationship is highly abstract; the earth’s ecosystem has seemingly been able to absorb increasing quantities of greenhouse gases (to this point at least). The relationship above clearly “looks” linear. But appearances can be deceiving and changing scales can produce strikingly different graphs. As illustrated below, even relationships that don’t “look linear” can be transformed by taking logarithms, in which equal distances on the y-axis represent identical ratios (see description here).

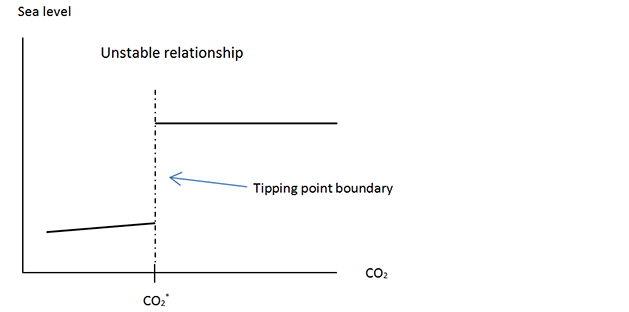

A non-linear relationship between greenhouse gases and sea level is shown below. In this case, the accumulation of CO2 initially has only a minor effect on sea level. At some point, however, a critical level, CO2*, is reached beyond which even an infinitesimally small increase in CO2 level results in a large discontinuous increase in sea level. (Think: loss of the Thwaites Glacier, other Antarctic ice sheets as well as the glaciers of Greenland). Beyond that point, further increases in CO2 have no discernable impact on sea level, though there may be other harmful ecological effects.

Some might ask: What does all this have to with Easter Island, resource depletion and international governance? Good question. The answer might surprise you.

Easter Island once had a thriving civilization that bequeathed a remarkable legacy of enormous carved statues (called “moai”) and, simultaneously, left a mystery. The mystery is who produced the statues. The late Stone Age culture that European travellers encountered in the early 18th century had neither the population nor the trees required to make the tools and wooden rollers, rope and sleds needed to move the moai from the quarry to their ceremonial stands. What happened?

The explanation accepted by many is that the population of the island increased beyond the environment’s carrying capacity.[1] Not to put too fine a point on it, the inhabitants of Easter Island degraded their environment by over-harvesting palm trees, which because of their slow rate of growth could not regenerate quickly enough to support the population. Once a tipping point threshold was crossed and the resources of the island could not sustain its population base, a Malthusian adjustment process was triggered, bringing about a collapse of the population.

Part of the problem was weak governance. Individuals probably regarded the trees as a free resource and harvested the palms as and when they pleased — the amount that any one individual in any one year harvested was too small to have anything other than a marginal impact on the total stock. Of course, all individuals thinking alike created a far larger effect with much greater destructive impact. Moreover, this tragedy of the commons continued even when it was recognized that the rate of harvest was outstripping the natural reproduction rate, since an individual's lifespan was shorter than the time it took for a palm to mature.

But it didn't have to be that way. Consider what might have been had early Easter Island society been led by forward-looking individuals who recognized the common pool problem in which the rate at which the trees were being harvested out-stripped the capacity of the palms to regenerate. And, if they had the means of enforcing conservation measures early enough, it might have been possible to encourage the cultivation of palm plantations and implement measures to reduce the consumption of palm wood, substituting from high carbon (wood) resources to low-carbon technologies in order to avoid the tipping point.

However, such measures may have been necessary conditions for avoiding disaster; not sufficient conditions. It might have been necessary to also reduce the birth rate to prevent the Malthusian adjustment mechanism.

In any event, lest anyone think that all of this is far removed from the modern age, the narrative could be taken from a discussion of the exploitation of the Grand Banks cod fishery. For 400 years, the rich fishing grounds were exploited as a source of protein for Europeans. But once modern technology was introduced, the rate of harvest outstripped the natural reproduction rate of the species and stocks declined precipitously. The cod fishery was at a tipping point — how close is probably reflected by the fact that the stocks have taken longer to rebuild than expected.

Governance was at the core of the strategy to rebuild the fish stocks. The starting point was Canada's assertion of territorial waters, supported by the law of the sea convention, and the right to enforce conservation measures. This was followed by the introduction of a moratorium on commercial fishing. Although that meant the end of a way of life for fisherman brought up on the cod fishery, the goal was to prevent a tipping point and the permanent loss of the fishery.

The stakes were undeniably high, but not on the Malthusian scale of Easter Island. Newfoundland cod fisherman received financial assistance and many left fishing to man off-shore oil rigs or move to the oil fields of Alberta. Similarly, climate change may not have Malthusian effects on population, but the preponderance of scientific evidence suggests it will entail human and financial costs that can be mitigated. Moreover, there is an issue of equity: those most harmed are likely to be the world's poorest; those who benefited the least from the degradation of the global environmental commons.

Some might argue that the analogy with Easter Island is false. They may be right. But absent effective governance and mitigation measures, we could see a race to the tipping point beyond which relatively small mitigation measures now (see Paul Krugman, here) may be too little, too late. At that point, we could be faced with much larger costs borne by all. In that event, future generations might ponder "what might have been" had we, the present trustees of the global commons, exercised greater care and more prescience.

[1] See: James A. Brander and M. Scott Taylor, “The Simple Economics of Easter Island: A Ricardo-Malthus Model of Renewable Resource Use, The American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 1, (March 1998), pp. 119-138; M. Scott Taylor, “Innis Lecture: Environmental crises: past, present and future,” Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 42, No. 4, November 2009.