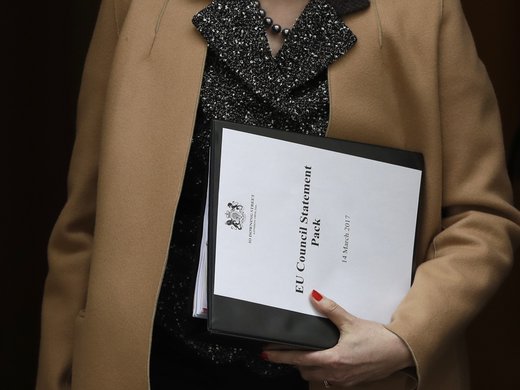

As Theresa May fires the starting gun on two years of negotiations with the European Union by triggering article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, there is much talk of driving a hard bargain.

Like their populist contemporaries, UK Prime Minister May and US President Donald Trump like to talk about getting better trade deals for their countries. They are on the wrong track. The goal of international trade negotiations should not be to outsmart the other side. The right objective is to develop durable, flexible and trusting relationships.

Trump’s fixation on getting the better of his opponents is understandable, although not excusable. After all, before being elected, the president of the United States was much more of a celebrity than a successful businessman. He never got along well with corporate types. For the British prime minister and her analogues around the world, the economic misunderstanding is harder to explain. They have enough contacts and relevant experience to understand how the economy really works.

But the mistaken mentality that helped make Trump’s The Art of the Deal a bestseller is widespread, and not just among neo-nationalist politicians. Many people assume that capitalist economies thrive on cutthroat competition and that international trade is supposed to be conducted like international sporting events — and may the strongest side win.

Professional economists mostly know better. However, students of the discipline usually spend their first year soaking up a Trump-friendly vision of economic activity as universally selfish. It would be better if the young were told the truth at the beginning.

The truth is this. A good economic deal of any size is one that gives both sides enough gain to want to keep on working together. The sort of exploitative deals that Trump loves are self-defeating in the not very long run. This principle holds for any contract, from the smallest purchase in a supermarket to the biggest international trade deal.

The establishment of trust and the promise of mutual advantage are particularly important for cross-border trade deals, because it is especially difficult for people from countries with different systems and rules to respect each other. The mind-numbing details of these agreements help reconcile initial differences, but even thousands of pages can only work if a good level of trust is built before, during and after negotiations.

To be fair, British leaders do sometimes say they understand they will have to compromise to reach their goals of establishing strong economic relations with the European Union and with other countries.

Similarly, some members of the Trump administration say the United States will respect Canadian and Mexican interests if the North American Free Trade Agreement is ditched. However, restoring lost trust will take a long time. Indeed, once the collaboration and respect that have been built up over decades has been wilfully destroyed, it may never return.

The erosion of trade trust also undermines some other foundations of modern prosperity. Without mutually beneficial deals, there will be less of the goodwill and two-sided respect that are essential for maintaining highly productive cross-border investments in research, development and design. Trade aggression also threatens economically vital international regulation.

These arrangements are under threat. Trump has intimated that he might stop respecting the rulings of the World Trade Organization (WTO). And a hard British exit from the European Union will exclude it from some of the organization’s biggest successes — strong non-trade relationships and respected regional regulators. The British will not replicate those with any number of supposedly advantageous trade agreements.

The futility of emphasizing advantageous contracts is not limited to trade arrangements among nations. Sharing and trust have done far more than legal contracts to make the modern economy great. Common purpose and mutual support lie behind the development and spread of all new technologies. Just as enforcing an agreed contract for a pound of flesh in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice would have destroyed the physical body, so too narrow deal-thinking damages the economic body, whether local or global.

International trade agreements both express and solidify trust. They are the skeleton of the global economic body. The bones are crucial, but not primarily because they reduce tariffs. That is the easy bit, a simple number. The flesh of cooperation is shaped around the WTO rules and the many detailed multilateral and bilateral agreements, not to mention the numerous international bodies, more or less backed by governments.

When May and her supporters are not being emollient about trade, they are frequently truculent. Trump is obnoxious to the core. These attitudes are all wrong. If their economies do manage to escape severe and durable damage from trade disruption, it will only be because their predecessors have built up a solid body of mutual reliance with long-standing trading partners.

Trump’s trade economics are sometimes described as opposed to the Brexit desire. The American wants protectionism, while the British yearn for free trade. The difference is real, but the similarity is much greater. They both want deals that first and foremost are good for the national self-interest. They have little concern for how the parties on the other side of the transactions fare, and even less for the common good of both. If they follow these principles, they won’t get what they want. They will end up with a collection of very bad deals.