As expected, United States President Donald Trump dealt a severe blow to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) this week. The JCPOA is the agreement made in 2015 between Iran, the United States, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the European Union that put major restrictions on Iran’s nuclear science activities, gave inspectors unprecedented access to Iran’s nuclear facilities and gave Iran relief from a range of trade and financial sanctions. Iranian officials have already threatened severe consequences now that the United States has decided to leave the agreement.

The United States is betting that Iran will acquiesce to a “better deal” that would prohibit Iran from conducting sensitive civil nuclear activities and address not only its ballistic missile program but also its policies regarding Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Imprudent retaliation by Iran could inadvertently bolster the American case for leaving the JCPOA, so a slow and subtle response (rather than a sudden move) is more likely. It’s uncertain whether the coming weeks will bring military tensions to the Gulf, new negotiations, a political crisis in Iran or a stalemate. The economic implications, however, can be sketched out quite clearly.

It appears that the United States will reinstate all sanctions that had been waived under the JCPOA. The effects of one American tool in particular — extraterritorial or secondary financial sanctions (that is, sanctions the United States imposes on US firms, prohibiting them from working with third-country firms who traded with Iran) — merit special attention. These sanctions illustrate the hornet’s nest of international law, economics and old-fashioned political competition that the United States may have stirred up.

The Economic Consequences of Pre-JCPOA Sanctions

Unravelling the full effects of the various UN, EU and American sanctions on Iran — the United States alone has issued sanctions related to nuclear weapons, terrorism, ballistic missiles and human rights through more than a dozen legislative acts and executive orders — is a tricky proposition, and beyond the scope of a brief article, but the writing is on the wall for at least a few of the economic impacts on the horizon.

Of immediate concern is how the private sector and foreign governments will respond to the renewal of American sanctions. To be clear, the economic blow to Iran won’t come from American business. The United States has done little commerce with Iran since 1979; a continuous series of executive orders and laws prohibiting Americans from trading with and investing in Iran have meant that, even during times of détente, economic exchanges between the two countries have remained insignificant. Instead, Washington hurts Iran with extraterritorial sanctions, which effectively penalize foreign businesses if they trade with Iran.

Perhaps the biggest hammer in the US sanction tool kit is the ability to deny people and firms access to the US financial system if they engage in prohibited economic activity with a third country (or to levy those firms with fines). For example, if a French firm were to purchase oil from an Iranian state-owned enterprise, using a French bank to settle the transaction with an Iranian counterpart via the Central Bank of Iran, under the United States’ nuclear sanctions regime — specifically the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) — the president could block that French bank from opening a correspondent account in the United States.

Given the size of the US banking system, the de facto status of the US dollar as the world’s pseudo-reserve currency, and the fact that commodities (including oil and gas) are overwhelmingly priced and traded in US dollars, US lawmakers and regulators have tremendous influence over how the rest of the world trades and invests.

Returning to the example of the 2012 NDAA, the act’s requirement that the president prohibit any bank from opening or maintaining a correspondent account in the United States if that bank also does business with the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) (or other banned Iranian financial firms) may have been one of the single most effective sanctions tools the United States used to bring Iran to the negotiating table in the first place. The NDAA also allowed the president to act against foreign central banks if they conducted transactions with the CBI in order to facilitate oil purchases.

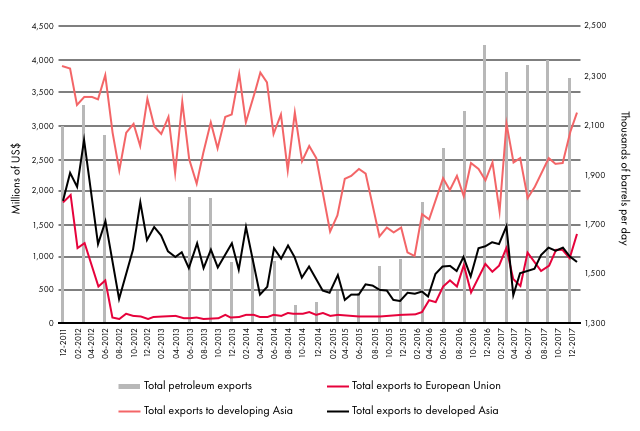

The president could waive that rule for private banks if he could certify that the bank’s home country was making efforts to reduce its purchases of Iranian oil. Nevertheless, the threat of being cut out of the US financial system was enough to dissuade many banks from doing business with Iran. A quick inspection of the data suggests that soon after the NDAA came into effect in early 2012, exports to the European Union in particular declined rapidly, from over US$1 billion of imports per month in February 2012 to US$53 million per month later that year. Of course, nothing happens in isolation, and other factors undoubtedly helped drive the rapid decline in Iranian exports, but the EU was receptive to American requests for it to reduce its Iranian oil purchases, allowing European firms to avoid being cut out of the US banking system.

Since the JCPOA went into effect in 2015 and the White House began waiving the NDAA sanctions, Iranian exports to the European Union have recovered to pre-NDAA levels (rising 25 times their sanction-period low; see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total Iranian Exports to Selected Markets (LHS) and Total Iranian Petroleum Exports (RHS), December 2011 to January 2018

Iran’s biggest single export is petroleum products, both crude and refined. While Iran’s economy has diversified significantly since the 1970s, over the past decade the oil and gas industry has made up an average of 14 percent of Iran’s GDP and accounted for 40 percent of its government revenues; its oil and gas exports have provided for most of its foreign exchange needs.

In the third quarter of 2014, Iranian oil exports averaged 1.37 million barrels per day (bpd), some 800,000 fewer than when the NDAA sanctions kicked in, and slightly more than half of the 2011 average of 2.5 million. Depending on the time period measured, and the assumptions made, it is easy to conclude that US sanctions removed as much as one million bpd from global oil markets. The devastation this inflicted on the Iranian government’s budget and the value of the rial, as well as on Iranian household finances, has been well documented. The White House is rolling the dice on the belief that it can repeat that squeeze on Iran’s oil and financial sectors, by driving down the rial and sparking an economic crisis that will lead to public demonstrations dwarfing this past winter’s protests, thus forcing Hassan Rouhani’s government to give the United States whatever it wants in return for relief.

Can the United States Recreate 2012?

Again, it’s difficult to forecast whether the United States Treasury’s announcement that the 2012 NDAA will be reimposed as part of the US withdrawal from the JCPOA will, in fact, knock a million barrels out of global markets.

As in 2012, there will be a 180-day “wind-down” period, during which states will be encouraged to make “significant” reductions to their purchases of Iranian oil. Secondary sanctions are unlikely to be imposed until early November 2018. Will the United States be able to significantly reduce Iran’s oil exports over the next six months? Market watchers assume that some — probably a few hundred thousand bpd — of Iranian oil will be locked out of the global market, due to insurers and banks being safe (rather than sorry) and staying away from any activity that might run them afoul of the US Treasury.

In 2012, there may not have been clear agreement among the United States and its allies about how to handle Iran’s nuclear ambitions, but there was an agreement that something had to be done. Today, the other parties to the JCPOA (China, Russia, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the European Union) are of the view that the JCPOA is working and that Iran is upholding its end of the bargain. With European imports of Iranian oil back near pre-NDAA levels, it is by no means a sure bet that they will reduce imports in a risky bid to fix an agreement that they do not think is broken — or in the context of global oil markets that are tightening.

Simply put, in 2012, Europe and the United States were on the same page about Iran. For the European Union, this made reducing trade with Iran economically tough, but politically doable. The United States didn’t need to threaten Europe to reduce its trade with Iran — they simply had to nudge and persuade them. Today, facing an extraterritorial sanctions threat from the United States, the European Union could look at reintroducing “blocking regulation,” a European Council regulation from the 1990s that was designed precisely to shield European firms from American sanctions on Cuba.

What Happens Next?

Just as Zhou Enlai said (even if he was misquoted) when asked about the consequences of the French Revolution, it is too early to say what Trump’s decision on the JCPOA will hold. The agreement could simply limp along, wounded and weak. Or, Iran’s leadership could leave it in a fit of pique, causing it to collapse. What is clear is that the United States has its work cut out. Washington’s new Iran policy puts it at loggerheads with not only Tehran, but the entire European Union, too.