The Economist magazine and Wolfgang Münchau at the Financial Times have recent articles on the polarization of European politics, which, it is argued, is driven in part by large debt burdens and the fiscal austerity — or “adjustment” — that has been used to contain debt.

How is that going?

Well, you be the judge. The chart below shows the evolution of debt-to-GDP ratios before and after the global financial crisis. Apart from Sweden, which has managed to keep its ratio constant, and Germany, which has stabilized its debt-to-GDP ratio following the shock, the story is pretty much one of rising ratios. Greece is notable for the very marked decline in its debt-to-GDP ratio following its restructuring in 2012. The relief was short-lived, however, and the ratio quickly returned to its pre-restructuring level. Ireland stands out, meanwhile, as having shifted from being the best performer prior to the crisis to among the high debt-to-GDP countries (i.e., above 120%) post-2008 as a result of the decision to assume the liabilities of the banking sector.

Why this deterioration in fiscal positions despite the policies of austerity?

Good question. The crux of the issue is often discussed in terms of "r-g" where r is the real (nominal rate less inflation) interest rate and g is real growth in the economy. For a given level of the stock of debt, the r-g condition determines whether a path of deficits net of interest payments (or a “primary deficit”) will lead to an explosive rise in debt — and hence is clearly unsustainable — on the one hand, or can be maintained on the other hand. If the real rate of interest is higher than the growth rate of the economy, continually running deficits is clearly going to be problematic. If the growth rate of the economy is higher than the real interest rate, however, and will remain higher, this is not the case.

The r-g condition helps to understand the situation in Europe. Some countries in Europe are experiencing near-Great Depression-like levels of unemployment and the global economy more broadly is experiencing stagnation and deflationary (not inflationary) pressures. And, while the ECB has reduced interest rates as a result of the crisis, with inflation at very low levels and deflation threatening, interest rates need to go lower still to reduce real interests. Yet, if the rates that the ECB can influence are already effectively zero, real rates are held up by the zero nominal bound. The same phenomenon was observed in the Great Depression; Keynes explained it in terms of a liquidity trap. Given the pervasive uncertainty about future prospects, everybody wants to hold cash. As a result, the additional liquidity pumped into the economy by central banks is simply held as cash. This has led some central banks (Fed, Bank of England and Bank of Japan) to engage in so-called quantitative easing: in effect, buying bonds directly to bring down, and hold down, bond yields.

Of course, one way to bring “r” down is to raise expected inflation. But that, clearly, is an anathema to Germany and, if the ECB is having difficulty hitting its own target of 2%, using the instruments at its disposal, it is unclear how it could engineer a higher rate.

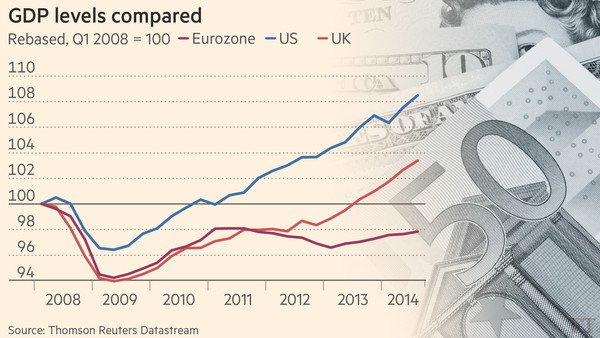

Meanwhile, austerity has had an effect on “g” in the r-g condition. Compare GDP levels (not growth rates) for the U.S., U.K. and the Eurozone in the chart below: fully six years since the onset of the global financial crisis, output in the Eurozone remains below its pre-crisis level. That is pretty much the experience of European countries that adhered to the dysfunctional gold standard in the 1930s. Enough said.

Source: Financial Times

There is another way of thinking about the debt-to-GDP ratio, D/GDP; an approach that some political parties in Europe may be considering. If the denominator isn’t growing (in part because of policies to reduce the numerator), they might argue, then perhaps the numerator can be reduced. Yes, debt restructuring would be disruptive. But, so too, Podemos would counter, are the social effects of the status quo. As Barry Eichengreen writing in the Financial Times has recently noted:

European officials continue to dance around the idea of writing down public debt, promising Greece lower interest rates and longer maturities but denying the need for more fundamental restructuring and for applying such measures more widely. The events of recent weeks make clear that they will not be able to dance much longer.