On July 21, seven artificial intelligence (AI) tech companies signed a set of eight voluntary commitments focused on “ensuring safe, secure and trustworthy AI.” The text of the document hit on most of the important topics of concern in the field, but it seems the tech companies walked away with more than they deserved. Company leaders were granted a photo op and media interviews from the White House lawn. What they provided in return were vague, voluntary commitments with no enforcement mechanism.

Why so skeptical? All of the big companies included have in the past paid fines in the billions of dollars (Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft) to regulators in the United States and the European Union in connection with violations of privacy and antitrust laws. These infractions were arguably not accidental. Companies take calculated risks that represent the cost of doing business in a highly competitive industry, often characterized by “races to the bottom” to gain control of markets such as search, shopping, social media and advertising.

And yet, enforcement works: I know first-hand, having worked on Meta’s Responsible AI team until November 2022, that tech companies are moved to do the right thing by firm regulation backed up by the threat of massive fines and reputational damage. When there is little or no regulation in place, teams working on topics such as responsible AI — one example being Twitter’s Machine Learning, Ethics, and Transparency team — can be abruptly downsized or eliminated.

It’s to be hoped that the new commitments are the “bridge to regulation” that White House staff make them out to be. An executive order on AI is in the works. However, such orders can easily be reversed by subsequent administrations. Perhaps the bipartisan popularity of AI regulation will serve as a bulwark against some reversals, but the power of tech industry lobbying is not to be underestimated — in fact, efforts are already under way to influence AI legislation and shift public opinion.

Another important path to explore would be for Joe Biden’s administration to work with Congress to pass strong legislation on AI. This approach has the potential to be much more durable and sweeping than an executive order. But gridlock being what it is, and given Congress’s protracted failure to regulate social media, relying on federal legislation seems a tall order.

The Biden administration should lean into this global effort in a major way, as time is of the essence, with new developments in the AI field proceeding at a dizzying pace.

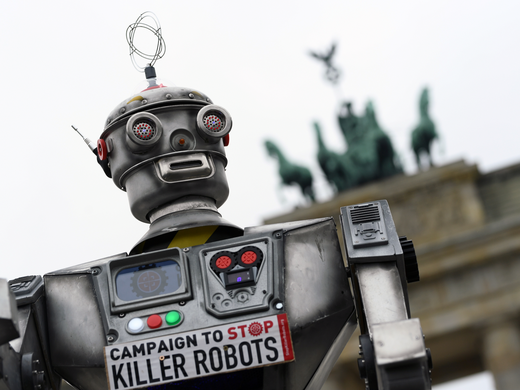

That is why the ultimate destination must be a binding, international treaty that creates a new intergovernmental body to govern AI globally. As is the case with controlling nuclear weapons and tackling climate change, a patchwork of regulation will leave certain AI harms dangerously unregulated. Powerful tools could conceivably fall into the hands of bad actors who could leverage them to produce disinformation campaigns, create bioweapons or deploy fleets of autonomous killer robots.

The good news is that it appears the Biden administration is already working in this general direction. An announcement that accompanied the new AI commitments mentions past meetings with 20 countries, as well as plans to participate in and support processes under way via the United Nations, the Group of Seven and the Global Partnership on AI.

The European Union’s AI Act, expected to pass before the end of 2023, may also serve as an effective model for global or semi-global regulations, though sadly it may not go into effect until 2025 or later. And even if the US Congress cannot move as quickly as the White House would like, President Joe Biden could parallel track domestic and international legislative work by supporting efforts such as the Council of Europe’s emerging draft AI Treaty (as long as it applies to private companies, not just government AI use) and the Center for the Advancement of Trustworthy AI’s campaign to help nations around the world put AI laws in place. China has made fast progress on AI regulation as well, and though there are some provisions in their domestic laws that would not be compatible with more democratic perspectives from countries like the European Union and the United States, there is still great value in engaging with China as a potential partner on numerous aspects of AI policy.

The Biden administration should lean into this global effort in a major way, as time is of the essence, with new developments in the AI field proceeding at a dizzying pace.

In tandem, the White House could push for more aggressive enforcement of existing laws that prohibit discrimination, whether at the hands of human beings or AI systems. In 2016, the Obama White House released a thoughtful report titled Big Data: A Report on Algorithmic Systems, Opportunity, and Civil Rights. Legal scholars argue that civil rights law can be used as a framework to launch broad campaigns against AI bias, a strategy that has yielded results in anti-discrimination lawsuits against social media companies like Meta. State and local laws (see, for example, New York City’s AI hiring law) can also make a difference, by forcing companies to come into compliance.

By working from local to global, the White House has a unique opportunity to advance the cause of enforceable, international AI regulation. I hope that my skepticism is unwarranted and that all seven companies that signed commitments last week will honour the full spirit of those commitments. In the meantime, it’s crucial that regulation of these technologies, in state, domestic and international arenas, proceeds rapidly, so that this transformational technology can truly deliver for humanity.