President Donald Trump surprised almost everyone, including his closest economic advisers and both free trade advocates and protectionists in Congress, when he announced last week that the United States would consider rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the huge Pacific Rim trade pact that he withdrew from days after taking office. Trump had heavily criticized the TPP, the signature economic deal of the Obama administration, even calling it the “rape of our country” during the 2016 presidential campaign.

In light of such statements, most observers believed the Trump administration intended to pursue only bilateral free trade agreements, if any at all. As Trump had pledged, his administration would focus on renegotiating existing deals, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the US free trade pact with South Korea, known as KORUS, in an effort to obtain better terms that would discourage American enterprises from manufacturing abroad.

Although Trump already rebuffed his own TPP reversal in a tweet earlier this week—writing that he didn’t in fact “like the deal for the United States. Too many contingencies and no way to get out if it doesn’t work”—that may not be the end of it, given his track record. Should the United States actually seek re-entry into the TPP, it would create enormous challenges, but also opportunities for both the United States and the 11 remaining parties to the agreement, among them close US allies Canada, Japan and Australia. The modestly revised TPP without the United States, known as the Comprehensive and Progressive TPP, or CPTPP, was signed on March 8 and is expected to go into effect for at least a majority of the parties by the end of 2018.

One doesn’t have to speculate too much to imagine that the growing threat of a trade war with China contributed to Trump’s reversal, although the administration has denied that the TPP and the potential China trade war are related.

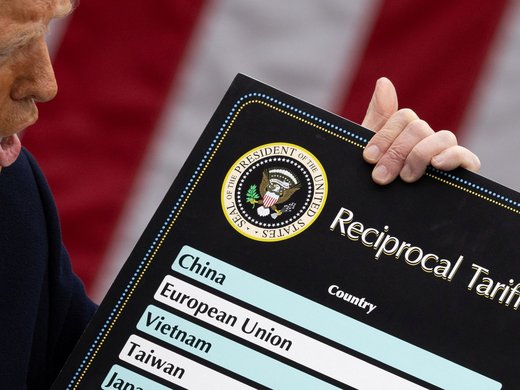

Some of Trump’s latest trade moves do not appear to reflect a coherent policy and strategy. The bogus “national security”-based tariffs on steel and aluminum can easily be dismissed as an unwise provocation of the closest allies to the United States — including Canada, Mexico, the European Union, Japan and South Korea — that will also lead to a loss of tens of thousands of US manufacturing jobs in industries that are dependent on steel and aluminum. Moreover, because of prior unfair trade cases against China, China was responsible for only about 2 percent of US steel imports and a slightly higher percentage of imports of aluminum. Therefore Chinese exports are only minimally disadvantaged by the imposed tariffs.

In contrast, the investigation into China’s trade practices by the US Trade Representative cannot be dismissed as irrational even if some may question its unilateral nature. Known as a Section 301 investigation, after the relevant section of the 1974 Trade Act under which it was carried out, it charged China with various “unreasonable” and “discriminatory” infringements that “burden US commerce,” such as forced transfer of technology, onerous technology transfer terms and outright theft of US and other foreign-owned technology. Yet the Trump administration’s threats of punitive tariffs, affecting several hundred billion dollars worth of bilateral US-China trade, will damage economic interests in both countries, if implemented. In particular, the US agricultural, automotive and aircraft sectors will be hit hard, as representatives of both industries have repeatedly advised Trump.

The Trump administration has threatened punitive tariffs because it sees the World Trade Organization as ill-equipped to deal with China, which has not opened its economy as was promised when it joined the WTO in 2001. China also repeatedly violates trade rules not only on intellectual property but also on subsidies and in relation to what the WTO calls “national treatment,” which prohibits imposing different taxes and regulations on similar imported and domestically produced goods.

The Obama administration also realized it could not hope to rein in China through the WTO. But rather than abandon the WTO, as Trump has also threatened, then-President Barack Obama opted to protect the United States and its other major trading partners by concluding separate, regional agreements setting out modern trading rules. The multilateral TPP exemplified this strategy. Among other things, the TPP greatly strengthens intellectual property protections, establishes tighter controls for state-owned enterprises and foreign investment, and facilitates supply-chain management — none of which have been achievable in years of negotiations at the WTO.

Despite the major benefits of US participation in the TPP as an economic and political counterweight to China, as the deal intended, the parties to the TPP are not likely to consider US re-entry at least until after the new CPTPP enters into force. Moreover, if the Trump administration seeks a “better” deal than the initial TPP and refuses to consider any concessions of its own, the other countries may simply walk away. The tense, ongoing NAFTA renegotiation and the revised US-South Korea free trade deal, the latter of which actually achieved very little for the United States, don’t bode well for US accession to the retrofitted TPP, or even other trade agreements. While Japan and Australia have repeatedly urged the Trump administration to reconsider its withdrawal from the TPP, they probably aren’t alone in realizing the difficulties involved in negotiating a US re-entry with the Trump administration.

Senior officials in Canada and Mexico, both of which are signatories of the CPTPP, are also likely to be particularly cautious as they have been engaged in difficult, one-sided and sometimes bitter NAFTA talks for over eight months. As it stands, even if a so-called NAFTA “agreement in principle” could be achieved soon, a revised and implemented NAFTA seems a long way off, since it would require extensive redrafting, as well as ultimate approval by both the U.S. and Mexican Congresses. The campaigning for July’s Mexican presidential election, already underway, and the U.S. mid-term elections in November will likely dictate a long pause in the renegotiations.

The Canadian and Mexican NAFTA negotiators, along with the other CPTPP parties that have followed the NAFTA renegotiations, are well aware of issues that would prove extremely contentious if the U.S. were to seek to open talks on rejoining the TPP. Those issues include investor-state dispute settlement, state-to-state dispute settlement, and rules of origin for automobiles and auto parts, all of which have already been well-settled in the TPP and CPTPP negotiations but where the Trump administration has demanded extensive changes in the NAFTA talks.

For these reasons alone, one should not overestimate the significance of this fleeting willingness of the Trump administration to consider a major shift in US trade policy, either through a re-entry into the TPP or, for that matter, into other regional trade agreements. “America First” is almost certain to remain the administration’s watchword when it comes to world trade.

This article was first published in World Politics Review.