There is a discrepancy between the situation workers confront today and the provisions regarding labour in trade agreements. The labour rights provisions in most trade agreements are outdated and incomplete and policy makers don’t even know if labour rights provisions actually improve labour rights conditions.

Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland recently put forward several ideas that could improve labour rights for all three signatories of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). She argued that renegotiation of NAFTA provides an opportunity for Mexican, Canadian and US officials to ensure that NAFTA works for all workers.

However, while Canadian officials deserve praise for thinking differently about how trade agreements might improve government respect for labour rights, labour rights provisions need a drastic rethink if they are to empower the twenty-first-century workforce.

NAFTA was the first twentieth-century trade agreement to address labour rights. Americans and Canadians pushed for labour rights language in the agreement for several reasons. First, they genuinely wanted to encourage their trade partners to respect labour rights. Second, they hoped that by including these provisions, they could gain the support of union leaders and labour rights activists. Third, they wanted to ensure that the Mexican government (and other trade agreement partners) would not use the agreement to lower labour standards in the belief that their exports would grow because they were produced with cheaper labour.

In theory, it makes sense to include labour rights provisions in trade agreements. With the incentive of enhanced trade regulated under a system of rules, officials of developing countries would improve their respect for labour rights. Policy makers in the developing world would comply because they could be challenged in a trade dispute if they didn’t. By complying, these policy makers would signal to business that labour rights are important, and thus employers must respect labour rights and inform workers of their rights under the law. Meanwhile, the newly empowered workers would organize and collectively bargain to gradually achieve higher wages and better work conditions. Finally, these empowered, richer and more productive workers would be more likely to consume more goods and services from the United States and Canada, creating a virtuous circle of trade agreements and labour rights. But what sounds good in theory has not always played out in reality, because some governments do not consistently enforce labour laws and workers are often unaware of their rights or unable to demand them.

NAFTA’s labour rights provisions were relatively weak and tacked on as a side agreement. In the years since NAFTA went into effect, labour chapters in US and Canadian trade agreements have come a long way. Based on recent agreements, we can expect that, at minimum, NAFTA 2.0 will include the labour chapter in the body of the agreement; it will promote all the core labour standards (freedom of association and the right to organize and collectively bargain; non-discrimination; and a ban on forced and child labour). The new NAFTA will also likely include binding and disputable labour standards, so citizens and unions in one signatory can challenge practices in another. Consequently, NAFTA 2.0 will be a major improvement on its predecessor. But it is also likely insufficient for today’s world of work.

During the September round of negotiations, Canadian officials signalled they wanted a more ambitious approach to advancing labour rights. They proposed that the United States look at its own labour practices and at the federal level repudiate state right-to-work laws. These state-level laws generally require union contracts to cover all workers — not just those who are union members. In so doing, these laws weaken unions by making it legal for workers who are protected under union contracts to opt out of paying membership dues (which makes it harder for unions to serve their members and, over time, harder for workers to join unions). The Canadian government also recommended that negotiators pay attention to the effects of trade agreements upon gender rights. Unfortunately, the Trump administration is likely to reject these ideas. More than half of the US states (28) have right-to-work laws that prohibit unions or employers from requiring that employees join a union as a condition of employment. Nor is the Trump administration likely to accept a gender lens: in early September, it rejected a regulation requiring companies to report anonymized data on the race/ethnicity, gender, job category and compensation of their workers. In short, the Trump administration isn’t even willing to require firms to report statistics on gender bias in the US workplace.

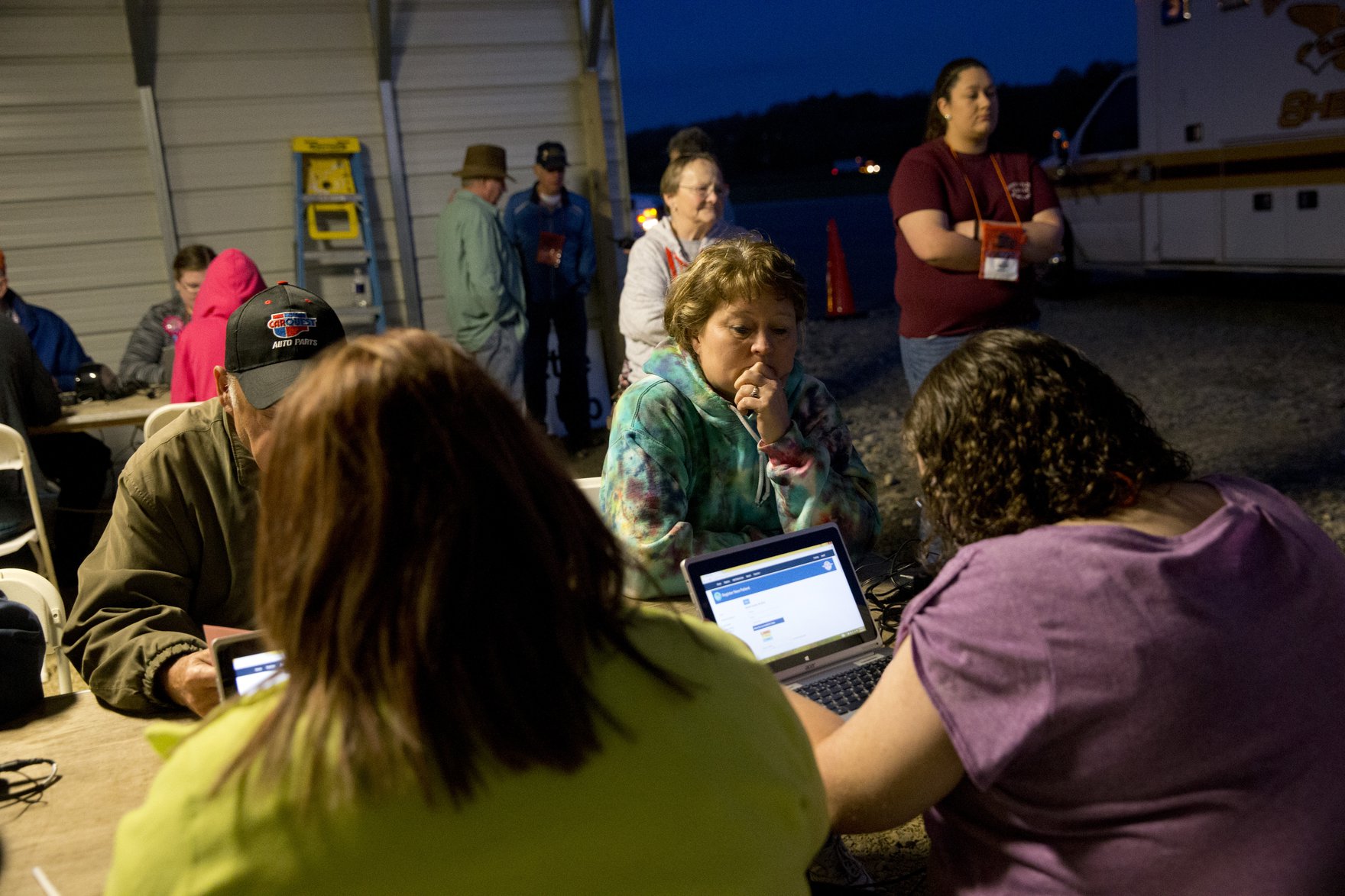

The truth is, if the three nations really want to help workers, they need to do several things differently. First, policy makers should revisit the reasons why workers feel so angry and powerless. In recent years, workers in all three countries have been buffeted by job losses, underemployment, technological change and economic insecurity. Despite rising productivity, many workers — especially those with fewer skills — earn less in real terms than they did 20 years ago. Meanwhile, over the two-plus decades since NAFTA was negotiated, technology and the spread of global value chains have changed what labour markets look like. For many of the world’s people, work is insecure. The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that the majority of the world’s workers, including informal, women, migrant and agricultural workers, are often excluded from national legal protective frameworks, leaving them unable to exercise these processes. Meanwhile, only 42 percent of workers paid wages or salaries are working on permanent contracts.

Researchers have not yet fully explained why workers feel insecure. Some cite factors such as globalization and technological change. Others attribute job insecurity to increased immigration, high rates of unemployment and underemployment, and the changed role of women and minorities in the workplace.

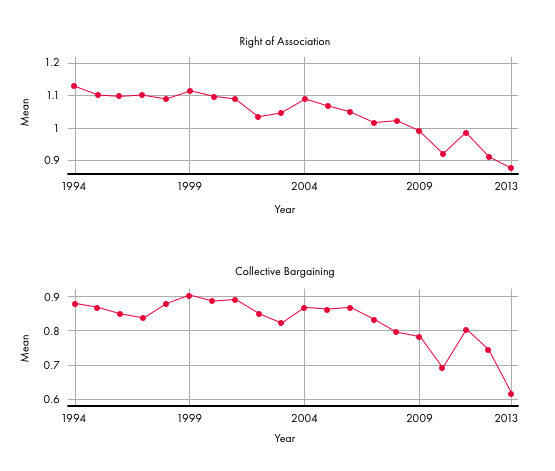

Whatever the reasons, policy makers need to investigate whether a decline in labour rights is affecting workers’ ability to demand better working conditions and higher wages. Here’s why. Several recent studies, such as those by Ronald Davies and Krishna Vadlamannati; Mark Anner, David Kucera and Dora Sari; and David Cingranelli and Zhiyuan Wang (2016), have shown that in most countries, freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining (FACB) have declined since the 1990s (Figure 1). Freedom of association refers to the right of individuals to establish and join organizations of their choosing, including societies, clubs and unions. Individuals who can freely associate can work together to hold managers or policy makers accountable. Collective bargaining refers to the right of individuals (often workers) to organize and achieve change as a group. Individuals collectively bargain in legislatures as members of caucuses or parties; in civil society groups, such as the Sierra Club; and in the workplace. FACB are not only labour rights, but also embedded in national and international human rights law. Without FACB, workers do not have ability or leverage to change the conditions that can over time lead to poverty and inequality, or limit democracy.

Figure 1: Trends over Time in Respect to FACB Rights

Researchers have found that policy makers at the national and local levels are changing their laws in ways that make it harder for individuals to use FACB laws. The decline in FACB is particularly noteworthy in middle-income and wealthy nations. For example, in a 2016 paper, Axel Marx and Jadir Soares found that FACB have declined significantly in high-income countries Greece and Spain, as well as in middle-income countries. In 2015 and 2016 reports to the UN General Assembly, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association Maina Kiai gave many examples of how these rights have been threatened. He cited Australia’s Tasmania State, where it is now a crime to a protest in a way that obstructs or prevents business activity. In 2015, he and several other human rights rapporteurs expressed concerns about Canada’s Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015, which expanded the definition of national security to include “the economic or financial stability of Canada.”

A decline in FACB can affect democracy both directly and indirectly. Without FACB, fewer workers are likely to join the middle class because, as noted above, workers will have less of an ability to affect their compensation. Researchers have long believed that the middle class is the front of democracy. If the middle-class population shrinks and becomes weaker, individuals or firms with greater funds and political influence can capture government agencies and agents, while those with less income have less influence. For example, the Special Rapporteur noted that Canada limits political activities by charities, (such as human rights organizations) but that non-charitable entities face fewer restrictions, a form of discrimination and possible influence peddling. Meanwhile, some scholars, such as Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk and Russell J. Dalton and Christian Welzel, have found that rising wage inequality has left the middle class increasingly dissatisfied with democratic institutions, policies and policy makers. Discontented individuals are more likely to turn away from traditional elites and long-standing policies and may be more willing to turn to populist leaders.

Taken in sum, if policy makers are making it harder for workers to associate, these workers can’t easily prod managers to raise wages as productivity increases, and they are also less able to influence government to adopt policies that help workers associate and collectively bargain.

While many workers blame trade agreements for creating job insecurity, we don’t know whether or if trade agreements such as NAFTA have played a role in this decline in labour rights or, as policy makers hoped, helped to reverse or postpone it. In fact, in a preliminary review of these agreements in 2016, the ILO admitted they did not know “to what extent these provisions have been effective.” A recent study of the limitations of EU trade agreements to promote labour rights (which used case studies) found that the agreements were inadequately monitored and the one-size-fits all-approach did not fit all political contexts.

Hence, if they want to truly meet the needs of the twenty-first-century workforce, NAFTA countries should do the following:

- Support a comparative analysis of existing trade agreements with labour rights provisions that have been in effect for more than five years. Researchers should examine whether binding labour rights provisions have encouraged governments to respect labour rights and whether these agreements empower people to demand their labour rights. They should compare these results to the effects of trade agreements without such provisions and to those such as NAFTA that use only aspirational language. Scholars should rely both on survey data (such as the World Values Survey), which can tell us if workers around the world feel more empowered, and on labour rights data sets (such as those of researchers Cingranelli and Wang at Binghamton University/Texas A&M, or the Global Labour Rights Indicators at Penn State), which can help us see if governments are increasing their respect for labour rights.

- Ensure that provisions in the agreement regarding core labour standards are clear and enforceable for contingent, part-time and temporary workers.

- Create a mechanism to explore how each NAFTA country can reform its labour laws to ensure that all contingent workers receive basic labour rights, the same as those received by workers with contracts. In so doing, these countries will empower more workers.

- Create a monitoring body to examine and report on government respect for worker rights and citizen awareness of labour rights in the three signatories.

- Encourage unions to offer cross-border services such as collective representation, benefits, training and other workplace services. In so doing, unions will become stronger and more competitive.

- Jointly explore how each country can ensure that its workers have the education and training to take advantage of twenty-first-century job opportunities, and have access to health insurance and pensions that are not at risk if they lose a job. In so doing, they will help workers feel more secure, and

- Finally, experiment. For example, trade policy makers should create a mechanism either within the agreement or as a side agreement that allows for temporary movement of low-skilled workers in areas outside agriculture and hospitality, such as barbers, massage providers and home health aides. These individuals should be allowed to offer services across borders.

In her August speech to Canada’s Parliament, Minister Freeland said, “If we don’t act now, Canadians may lose faith in the open society…and in free trade — just as many have across the Western industrialized world. This is the single biggest economic and social challenge we face. Addressing this problem is our government’s overriding mission.” To truly face that challenge requires that she and other negotiators think differently about what trade agreements can and should include.