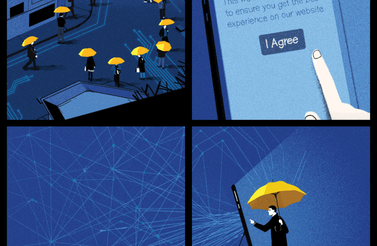

While the possibility of new regulation looms over the technology industry, an increasing number of social media platforms are taking measures to demonstrate their responsibility. But tech companies’ new embrace of responsibility could fuel — rather than diminish — calls for regulation.

For example, Pinterest recently faced criticism for enabling the spread of misinformation about the efficacy and side effects of vaccinations. In response, the company originally disabled search results related to vaccines entirely, and later announced that it would limit results to posts from authoritative sources (such as the World Health Organization or the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Pinterest’s decision about its search function highlights the crucial role that platforms play in people’s research on and decisions about important subjects, from public health to politics. And it symbolizes something of a turning point for platforms that rose to success on a bounty of user-generated content. Part of these sites’ appeal was that they were a space for the opinion of the average person, and not necessarily an authoritative or government source. The lure that these platforms offered was the idea that anyone could be authoritative, and that their contribution to a subject — whether based on evidence or opinion — could be just as valuable.

But in Pinterest’s case, this idea of user credibility came into question as a public health concern broke out on the platform; posts that were disputing traditional authorities’ statements about vaccinations for preventable diseases such as measles and polio were shared widely, and in some cases, taken as truth. The popularity of the posts provoked a shift in how the platform regarded its editorial responsibility; Pinterest went so far as to argue that “health misinformation is contagious,” acknowledging the larger cultural war of viral content in influencing popular perceptions of vaccines and public health efforts.

Other platforms have taken similar measures to limit the impact of content that seeks to undermine confidence in vaccines. In March 2019, Facebook said they would demote pages and groups that spread misinformation about vaccines and reject any related advertising. They also said they would do the same on Instagram, but such content is still easy to find.

These efforts come on top of collaborations between social media platforms and traditional news organizations such as the CBC and the BBC, who have formed a “Trusted News Charter” and are seeking to “fight disinformation” and create an “early warning system” to alert people of campaigns designed to manipulate them. These companies have also been meeting with security and intelligence agencies to prevent attacks and influence campaigns designed to subvert elections.

As one of the largest platforms — and perhaps the platform facing the most criticism for the spread of misinformation — Facebook has started taking measures to curb fake news by accompanying posts with publisher information, and by providing a map of where the story has been shared. The company had previously partnered with Snopes, the news website that specializes in debunking urban myths and false news, paying Snopes to help fact-check items posted on Facebook, but earlier this year Snopes ended the partnership, questioning whether its efforts were having any impact.

Given its global presence, Facebook also came under fire for not having sufficient content moderation staff, and in particular, staff who speak languages other than English, in order to effectively moderate posts around the world. Facebook has since made efforts to hire content moderators in as many languages as possible, and both CEO Mark Zuckerberg and COO Sheryl Sandberg are said to be “incredibly involved” with the sensitive content issues that are currently challenging the platform.

Nonetheless, the general perception among regulators is that Facebook could be doing more but chooses not to. Rod Sims, the chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, was quoted in The Guardian as saying that Facebook is “palming off responsibility” when it would be quite easy for them to remove content that is blatantly false.

It seems, however, that Facebook and Pinterest, and likely most other technology giants, aren’t necessarily evading responsibility right now. In fact, they appear to be in a rush to engage in voluntary actions in the hopes of mitigating any mandated actions or those that come with fines (as have been established in Europe).

They aren’t wrong; regulation is on the horizon. Policy makers around the world, including those participating in the International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy, are often discussing whether and how platforms (usually with a focus on Facebook) should be held accountable for the content they host, what criteria should be used to determine accountability and what enforcement would look like.

There is also a growing network of civil society and advocacy organizations (like noyb, Algorithm Watch, the Open Markets Institute and Data & Society) that are engaged in research and mobilizing to demand improved rights for users and citizens, whether they be focused on data privacy, algorithmic transparency or anti-trust.

Of course, any discussion around the regulation of social media platforms will raise questions around platform neutrality and the once-celebrated nature of platforms — that anyone with an internet connection can publish about any subject.

A few big examples demonstrate the possible, positive impact of platforms stepping in to limit and halt misinformation. Pinterest’s decision to prioritize reputable information about vaccines could be a necessary step in curbing a public health crisis. And Google’s 2016 decision to cooperate with the British government to redirect users searching for terror-related information to counterterrorism resources may have prevented further online extremism. But the platforms’ willingness to engage in such initiatives should also be carefully considered.

Social media companies began with the premise that they were neutral entities that enabled users to express themselves freely. It’s important that these companies (and regulators) are realizing the socio-political power of platforms. But as governments make efforts to ensure platforms wield that power more responsibly, democracy and social media’s once-celebrated freedom to publish should be taken into consideration too.