The federal election has come and gone and the parliamentary map is largely unchanged. Politicians can call this a success; Canadians might say differently. We are locked into another minority government, which poses unique challenges for governance, especially on national security matters, acknowledged by all as a prime duty of government even if no word of this was breathed on the campaign trail.

National security is a divisive political issue. The major parties approach national security differently, but passionately. The New Democratic Party (NDP) is rights-focused and looks to solutions to national security that involve international agreement and cooperation, which are in short supply these days.

The Conservatives want to take an aggressive approach to relations with China, not only in terms of protecting Canada’s democracy but also in our international relations, to pivot Canadian foreign policy toward the Indo-Pacific and rebuild a close security relationship with the United States.

The Liberal Party election platform offered a series of unfocused statements attached to a host of detailed commitments that hint, but only that, at new directions for national security, including addressing climate change security impacts, dealing with foreign interference in our democracy and addressing our economic security.

Most of these commitments went uncosted in the that platform document; some were restatements of previous promises. Both the NDP and the Conservatives were critical of the government’s pandemic preparedness. Strangely, the issue of poor pandemic preparedness, the most significant national security crisis since the 9/11 attacks, made no impact during the campaign.

Where do these divergent approaches and vagaries leave us as the next Parliament convenes? The first thing we have to fear is that reputational costs will lead the Liberals to devote little attention to better preparing Canada for future pandemics. Without the cover of a majority government, any effort to learn lessons from our failures at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic may be sidelined, which would represent a serious failure of leadership.

If pandemic preparedness, including measures to improve our health security intelligence, risk assessment, decision making, and public communications systems are sidelined for political reasons, where might a minority government go in readying Canada to meet the rapidly developing security impacts of climate change? One commitment within the “Cleaner, Greener Future” portion of the platform promised to “expand the office of the National Security and Intelligence Advisor to keep Canadians safe as climate change increasingly impacts our domestic and global contexts.”

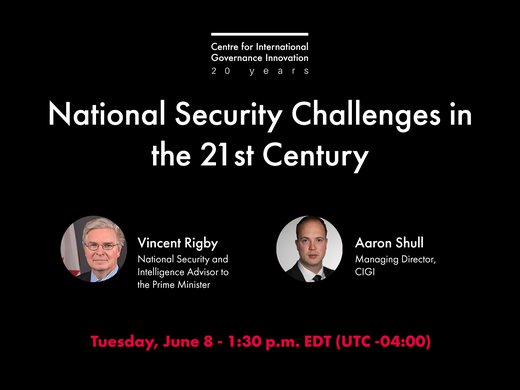

What this might mean in practice is anyone’s guess. But here is the thing: the national security and intelligence adviser (NSIA), a senior official at the Privy Council Office, is the prime minister’s adviser. Beefing up the office of the NSIA only makes sense if its work gets the full attention of the PM, and if he is willing to take ownership of the climate security file — by advancing a real climate security strategy, taking concrete measures to improve Canadian mitigation capacities at home, and contributing to global assistance for countries most at risk of being deeply affected by climate change. There is no reason to suppose that strong action on the climate security file would not have the support of both the Conservatives and the NDP, even if their priorities might be different.

The Liberals did take one important step pre-election by announcing a plan to create a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Centre of Excellence in Canada on Climate Security.

Work on this now needs to be accelerated. The Conservatives suggested a different Canadian NATO Centre of Excellence for Arctic Defence. There is potential convergence here, as climate security impacts will be heavily felt in our Northern and Arctic regions and will require more efforts at sovereignty protection. Canada should take a global leadership role on climate change and the Arctic, including its security impacts. The NDP would surely be on board with this.

Threats to economic security are another key national security challenge, and one that also went unmentioned on the campaign trail. Liberal platform promises to strengthen Canada’s regime for foreign direct investment to protect against adverse foreign ownership should find cross-party support. On this, both Liberals and Conservatives are China hawks.

So should the Liberals’ promise to introduce legislation to protect critical infrastructure, even if there will be sparring over the details. The Conservative desire to advance a Canadian approach to mining and processing of critical minerals, especially those crucial to a new, carbon-free, economy such as lithium, should have Liberal support. More win-win.

The challenges of advancing Canada’s national security needs in a minority and divisive parliamentary setting will drive action in the direction of issues where consensus is achievable. But selecting disparate agreed items from the party platform cafeteria menus will not be good enough. Such a piecemeal approach, while satisfying political needs, will fail to achieve greater security unless it is accompanied by a coherent strategy.

A minority government cannot achieve all its detailed objectives, but what it can do is offer Canadians a real sense of how it understands the threat landscape, what key national security priorities are, how it wants to operate to meet national security threats generated at home and abroad, and what capacities it needs to achieve national security goals to keep Canadians and their democratic system safe.

A strategy doesn’t need opposition political buy-in, doesn’t need cross-party consensus, doesn’t require the passing of legislation, or even new spending. What it needs is political will and leadership.