ChatGPT can write decent jokes. Text-to-image and text-to-video systems continue to improve. Moreover, images generated by artificial intelligence (AI) have already bested human artists in competitions. The way AI is trending, it’s not inconceivable that in five years we will be watching movies completely written and animated by machines.

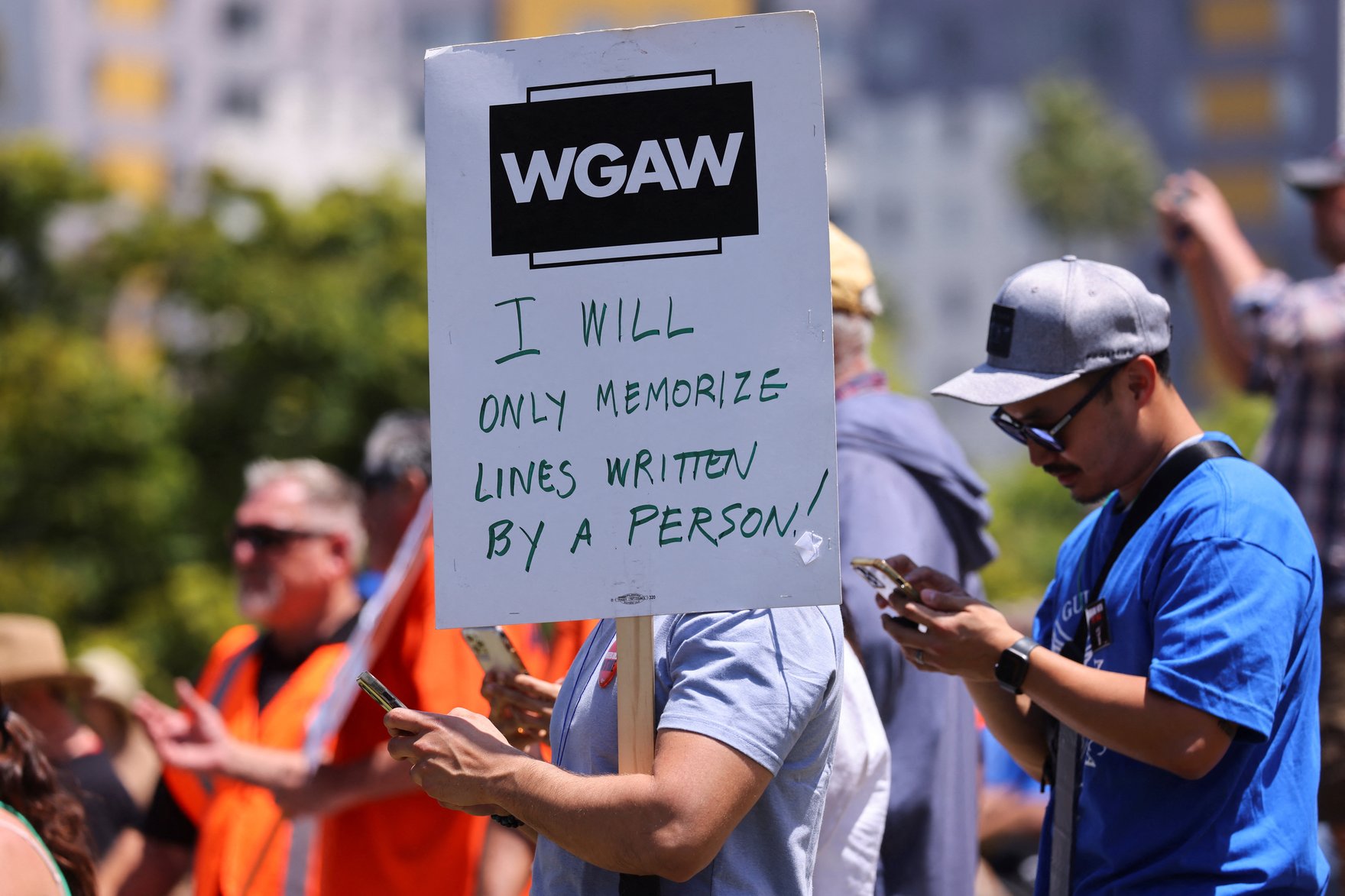

It’s not surprising at all, then, that the use of AI in screenwriting has been a core issue in the current Hollywood writers’ strike, which has ballooned to become one of the biggest in nearly half a century, drawing in not only writers but also actors like Jason Sudeikis and Susan Sarandon. The stated goal of the union representing the Writers Guild of America is simple: to “regulate use of material produced using artificial intelligence or similar technologies.”

Are screenwriters right to worry about this technology? To a degree, certainly. AI will transform their profession, much as it is changing others. However, current gaps in AI technological capabilities means that screenwriters will continue having a place in our brave new digital world.

Consider The Frost, a recently released 12-minute movie in which every shot was generated by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2. The film is impressive, by virtue of the fact that it was created completely with an AI system. But both thematically and stylistically, it leaves a lot to be desired. Crucially, the producers fed DALL-E 2 a human-generated script and creatively tweaked and edited the different shots that DALL-E 2 generated. The Frost is no Citizen Kane and its production still required much human effort.

Similarly, although AI models can already write passable fiction, they are far from being self-sufficient in this regard. For example, Sudowrite’s Story Engine system was recently in the news for having enabled a writer to generate a 22,500-word cyberpunk novella over the course of a single weekend. But a human was instrumental in all steps of the writing. Adi Robertson, the author in question, estimated that she generated roughly 6,500 of her own words to produce the 22,500 words in the novella. Most of Robertson’s own words were rewrites of faulty AI prose. Robertson noted that the computer-generated prose was often either too corny, error-prone or repetitive and clichéd. Robertson noted that she “lost count of the number of times” the AI system “had a chill go up someone’s spine.”

The examples of The Frost and The Electric Sea, Robertson’s AI-generated novella, illustrate an important point: while generative AI technologies are capable, they are nothing without the humans that guide them. It seems there is an art to knowing how to prompt AI systems and critically evaluate the merit of their output. Anyone can ask ChatGPT to write science fiction. But without selective prompts and a keen eye, the resulting story will be banal and, often, comically repetitive. We are still far from a world in which a studio executive can forget about employing screenwriters, let alone one in which a large language model can fully produce the next Marvel blockbuster. AI models will certainly continue improving, just by virtue of scaling, but given the importance of editing and iteration in the creative process, I find it unlikely that human screenwriters will ever be completely left out of the loop.

In the future, screenwriters will likely work in tandem with AI systems. For instance, a late-night writer might ask an AI for five different jokes on a particular theme and then refine the best. In this world, AI does the dirty work, freeing artists to optimize their creativity. It’s worth noting that the screenwriters on strike seem comfortable with such a scenario, as they have been in favour of permitting the use of AI in screenwriting, so long as the writers’ credits and residuals remain unaffected.

Even as AI technology improves, and generative text models become more logically consistent and less corny, there will still be room for writers and artists more broadly, to do what AI has so far been utterly incapable of doing: namely, to generate completely new and novel art. AI systems can make trailers for The Lord of the Rings in the style of Wes Anderson, because they have encountered both The Lord of the Rings and Wes Anderson films in their training data and learned the patterns that define them. But there are new styles of television, film and script that have yet to be invented that AI systems have not seen and cannot create. AI can give you more Wes Anderson, but I doubt it will become the new Wes Anderson any time soon.