As Ukrainians face nightly drone and missile attacks by the Russian army, Ukraine’s armed forces are holding on despite the asymmetric nature of the conflict. As of 2025, Russia is believed to have approximately 600,000 active-duty troops in or around Ukraine, with an estimated 1,320,000 around the world, and an aircraft collection more than 10 times larger than Ukraine’s (4,292 compared to 324). By comparison, Ukrainian President Volodymr Zelenskyy stated earlier this year that Ukraine has approximately 880,000 active-duty personnel.

And yet, despite the imbalance, on June 1, Ukraine launched Operation Spider’s Web, using hundreds of low-cost, short-range one-way drones to strike deep into Russian territory, damaging at least 11 Russian strategic bombers.

The conflict in Ukraine underscores not only the centrality of technology in modern warfare, but also the capacity of inexpensive drones to destroy expensive aircraft. Indeed, the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and drone technologies is reshaping warfare, from military operations to intelligence gathering and strategic decision making.

Russia’s invasion in 2022 forced the Ukrainian army to modernize its military arsenal at an unprecedented speed, making it much more innovative than the armies of many other countries around the world. Ukraine did not have a choice: Serhii Sternenko, a young Ukrainian lawyer and drone advocate, told The New York Times that he believed his “country’s survival…had come to depend on drones,” explaining that “90 percent of the Russian equipment that was destroyed by Ukraine was destroyed by drones.”

In 2023, President Zelenskyy announced the production of one million first-person view (FPV) drones. For 2025, the target is 4.5 million. The country has also mobilized engineers, tech companies and civilians, relying on their knowledge and manufacturing skills. Ukraine now has over 80 drone manufacturers producing domestic alternatives to widely used Chinese models for a variety of tasks.

For example, UADAMAGE, whom I spoke to for this article, is revolutionizing drones and remote sensing for demining and damage assessment, training demining teams on the ground to achieve their missions 10 times faster and cheaper, and lowering risks of casualties. The company has received support not only from the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine and the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine but also from international agencies and foreign governments that believe that its techniques can be adapted to other contexts, from defence to managing wildfires.

This doesn’t mean that expensive high-tech drones and other technologies are not useful, but rather that modern armies should consider using the cheaper drones as well.

Small commercial FPV drones that cost as little as US$400 (by comparison, Russia’s Shahed-136 long-range drones can cost up to $100,000) have proven quite destructive on the field, a lesson to the world’s largest armies who tend to invest in large, expensive equipment. Eric Schmidt, the chair of the US National Security Commission on AI and a former CEO of Google, stated last year that cheap drones have rendered legacy systems such as tanks obsolete and encouraged the US military to invest better.

While his words are self-interested — Schmidt is investing in new-generation drones for Ukraine — the ongoing war seems to prove his point to some extent. Low-cost drones are becoming increasingly critical in warfare, including in entrenched terrains, where large, expensive drones cannot be transported. Furthermore, the use of such drones requires long-term training. For Ukraine’s army, which is now made up of many drafted citizens, the learning process would have taken too much time.

The US military, through the Replicator Initiative, invests in costly technology such as Anduril’s Altius-600 and AeroVironment’s Switchblade one-way attack drones (CDN$80,000–$110,000 per unit), as well as Predator and Reaper drones (at “tens of millions of dollars” per unit). Interviewed for a New York Times article published in July, Trent Emeneker, the project manager for the Autonomy Portfolio at the military’s Defense Innovation Unit, said American war fighters have not been given what they need to fight in modern warfare as the United States lags behind China and Russia in manufacturing drones. This doesn’t mean that expensive high-tech drones and other technologies are not useful, but rather that modern armies should consider using the cheaper drones as well.

Drones are Key for Canada’s Defence

As Canada ramps up it defence budget, it should consider investing in low-cost precision systems, including uncrewed aircraft. According to a 2024 internal Department of National Defence (DND) report, the combat readiness of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) is in dire condition, with much of its equipment considered “unserviceable.” To help bridge the gap between Canada’s spending and that of its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies, and considering that its budget will never reach the level of the United States or China, the CAF could learn from Ukraine and focus on building an affordable, adaptive military-tech ecosystem.

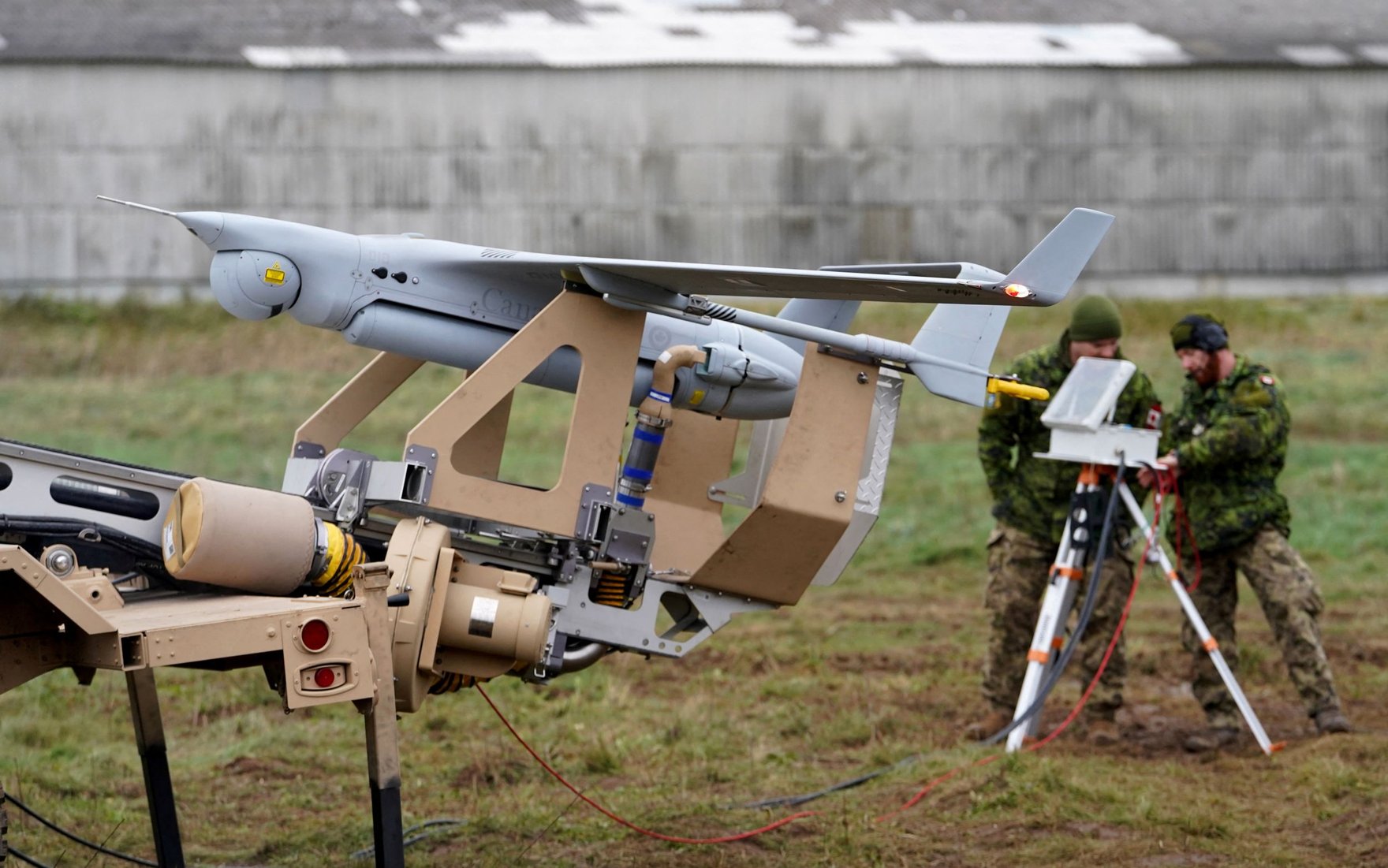

In its 2024 Our North, Strong and Free strategy, the DND stated that it “will explore options for acquiring a suite of surveillance and strike drones and counter-drone capabilities.” Production of combat drones started in December 2024, but these are MQ-9B drones, which cost US$30,000,000 per unit and will not be delivered until 2028. Furthermore, in November 2024, the CAF said that it had no plans to acquire FPV drones, despite their proven use in certain terrains and cost-effectiveness.

In the current geopolitical environment, the CAF should adopt a bolder approach: it has the capacity to do so, if it finds the will. Canada has the advantage of having a vibrant AI and tech community, especially in Quebec. Indeed, the province is home to companies such as Rheinmetall Canada, CAE Defense & Security and Teledyne FLIR, which have the technical expertise required to boost Canada’s defence arsenal, as well as Canada’s economy.

Rheinmetall Canada, one of the largest providers of land defence systems, specializes in, among other things, robotics and multi-rotor drones. CAE has multiple training facilities and systems, and already trains US Army drone pilots. Finally, Teledyne FLIR, which has offices in Quebec and Ontario, is already providing the DND with 800 small SkyRanger R70 drones to send to Ukraine.

Another lesson Canada could learn from Ukraine is the country’s Brave1 tech cluster, a Ukrainian government-backed defence tech accelerator, which combines public funding, private sector ingenuity and real-time battlefield feedback. In the words of Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine, Mykhailo Fedorov, “BRAVE1 has become the largest angel investor in defense tech in Ukraine.”

While Canada is not at war, similar public-private-civilian collaborations could boost innovation and reap economic and technological benefits for Canada. The current geopolitical uncertainty, from Eastern Europe to Gaza to the Indo-Pacific and NATO, requires innovation and technological shifts. While Canada may never match the scale of China’s or the United States’ military, it must adopt a bold vision to secure its future in an unpredictable world.