Success in artificial intelligence (AI) is not limited to data and algorithms. The third component that determines success in research and applications is advanced specialized AI chips that provide increased computing power and storage, while decreasing energy consumption.

Companies that have access to leading-edge AI chips are essentially in the fast lane, where improvements continue to be rapid and mutually reinforcing.

China has relied almost solely on the United States to import advanced microchips, but the US-China technology war has disrupted China’s access to these critical components of AI success. We are at a turning point: will America’s unprecedented technology export restrictions cripple China’s AI ambitions? Or will it force China to race ahead on its own?

Data arguably constitutes China’s primary AI advantage. With fewer obstacles to data collection and use, China has amassed huge data sets that do not exist in other countries. But, China’s achievements in AI applications lack a robust foundation in leading-edge chips, leaving them vulnerable to imposed supply disruptions, as we’re seeing amid the coronavirus pandemic.

China’s AI strategy has largely neglected the role of computing power as it was assumed that the necessary chips could always be purchased from global semiconductor industry leaders. Until recently, AI applications run by major Chinese technology firms like Alibaba were powered by foreign chips, mostly designed by a small group of leading semiconductor firms in the US. The outbreak of the technology war, however, has blocked China’s access to advanced chips from the Americans.

As part of the trade war that the US is prosecuting against China, the Trump administration has sharply increased the range of restrictions on China's access to advanced US technology. Huawei and China’s leading AI start-up companies are on a trade blacklist that bars them from buying advanced semiconductors and software from US companies without the government’s approval first.

The US Treasury has drastically expanded the mandate of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. As a result, Chinese investment in US firms with sensitive technology faces almost insurmountable hurdles.

Faced with these US restrictions, China can no longer count on secure access to leading-edge AI chips. China’s leadership believes that a robust domestic AI chip industry is needed if they want to sustain its still highly fragile achievements in commercial AI applications. From a US perspective, it is somewhat ironic that US restrictions on technology exports may actually strengthen China’s resolve to accelerate the development of its domestic semiconductor industry.

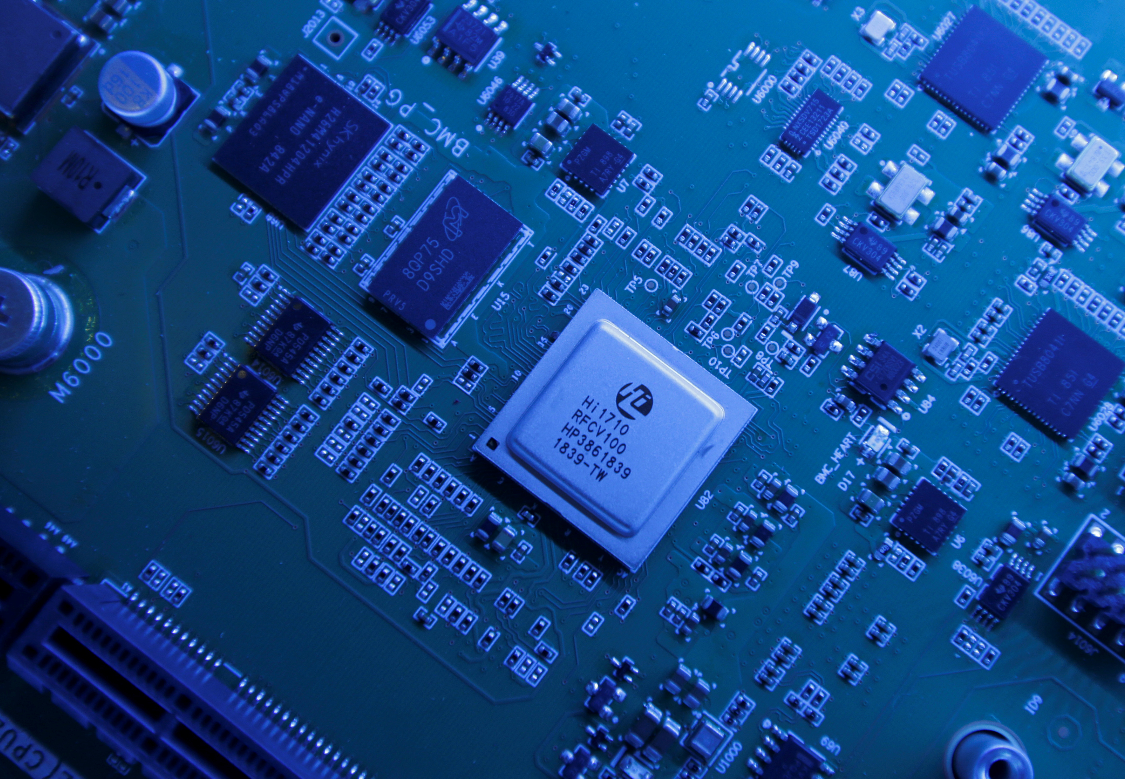

China’s AI chip industry is mounting a vigorous catch-up campaign. Both the large players like Huawei, Alibaba and Baidu, as well as other companies with a value of over US$1 billion each, have developed new innovative AI chip designs. Industry experts consider Huawei's AI chip development strategy to be technologically brilliant.

Nevertheless, China continues to lag considerably behind the US in the depth of its domestic chip design and fabrication of semiconductors. For instance, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), China’s largest semiconductor foundry, continues to lag more than three years behind in leading-edge process technology.

While the US semiconductor industry has consistently retained nearly half of the global market, China-based production is only around 5 per cent. Reflecting these weaknesses, China’s semiconductor trade deficit has more than doubled since 2005, surpassing crude oil to become China’s biggest import item. This massive import dependence explains why the Chinese leadership has made it a priority to catch up and forge ahead in this industry.

America’s technology export restrictions will no doubt slow China’s push into AI and semiconductors. But there will be immense collateral damage. Technology warfare against China may end up hurting the US even more, in particular its semiconductor and AI industries.

US suppliers will suffer as Huawei responds to the US ban by doubling down on efforts to become self-reliant and sourcing components from alternative suppliers based in Europe and elsewhere in Asia. US semiconductor firms are therefore losing their privileged status as trustworthy suppliers.

While decoupling between the US and China is real, it remains porous and meandering, and hence may leave room for pragmatic counter-strategies. The US needs to return to a policy that promotes rather than disrupts the rule of law in international trade, to regain stability, predictability and a more equitable distribution of gains from trade. It will take quite some time to repair the tremendous damage done by current US policies.

China, in turn, needs to reconsider the notion that the country can only progress in AI if it pursues a zero-sum competition policy in its relationship with the US and other advanced countries. China should provide safeguards to foreign companies against forced technology transfer, through policies such as compulsory licensing, cybersecurity standards and certification, and restrictive government procurement policies.

In short, technology warfare based on crude techno-nationalism is threatening to destroy AI’s global knowledge-sharing culture. This is true both for the “America first” doctrine and for China’s attempts to claim sovereignty over its cyberspace through the Great Firewall.

This article originally appeared in South China Morning Post.