China has sought to harness the digital economy as a “new engine” of economic growth since 2015 in response to slowing growth and long-standing structural challenges. Initiatives such as “Internet Plus” and “Digital China” have promoted frontier technologies such as fifth-generation mobile networks, the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain. The digital economy,1 fueled by tech giants such as Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, JD.com, Xiaomi, ByteDance and Huawei, has become a significant contributor to China’s economic growth, making up 42.8 percent of GDP in 2023, up from 27 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, the digitalization of traditional sectors — including agriculture, manufacturing and services — has also contributed to this rapid growth.

At the same time, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has expanded into frontier areas such as 5G, IoT, smart cities, AI-based facial recognition, data centres, cloud computing, and submarine and territorial cables since the launch of the Digital Silk Road (DSR) initiative in 2017. This expansion has developed digital infrastructure and laid the foundation for digital trade with BRI countries and beyond.

China’s Changing Approach to Digital Trade

Digital trade is defined as “all international trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered.” It includes both digital ordering trade (synonymous with international e-commerce, where goods or services are ordered online but goods are delivered physically) and digital delivery trade (services delivered remotely over computer networks).

China’s evolving approach to digital trade has not been driven by design but by the rise of e-commerce platforms over the past 10 years, amid rapid growth in internet infrastructure and online payment systems. The BRI and the DSR have, however, provided an enabling policy environment for the country’s large e-commerce platforms to expand overseas, evolving into major cross-border e-commerce players.

Starting with its first memorandum of understanding (MoU) on e-commerce with Chile in 2016, China had signed bilateral e-commerce MoUs with 33 countries by July 2024. In 2021, Beijing introduced the concept of “Silk Road E-commerce” in its fourteenth five-year-plan, the country’s overarching economic blueprint. During this period, various governments introduced supportive policies, including tax reductions and simplified administrative processes. The establishment of 165 cross-border e-commerce pilot zones has streamlined transaction processes, reducing associated costs by integrating facilitating measures.

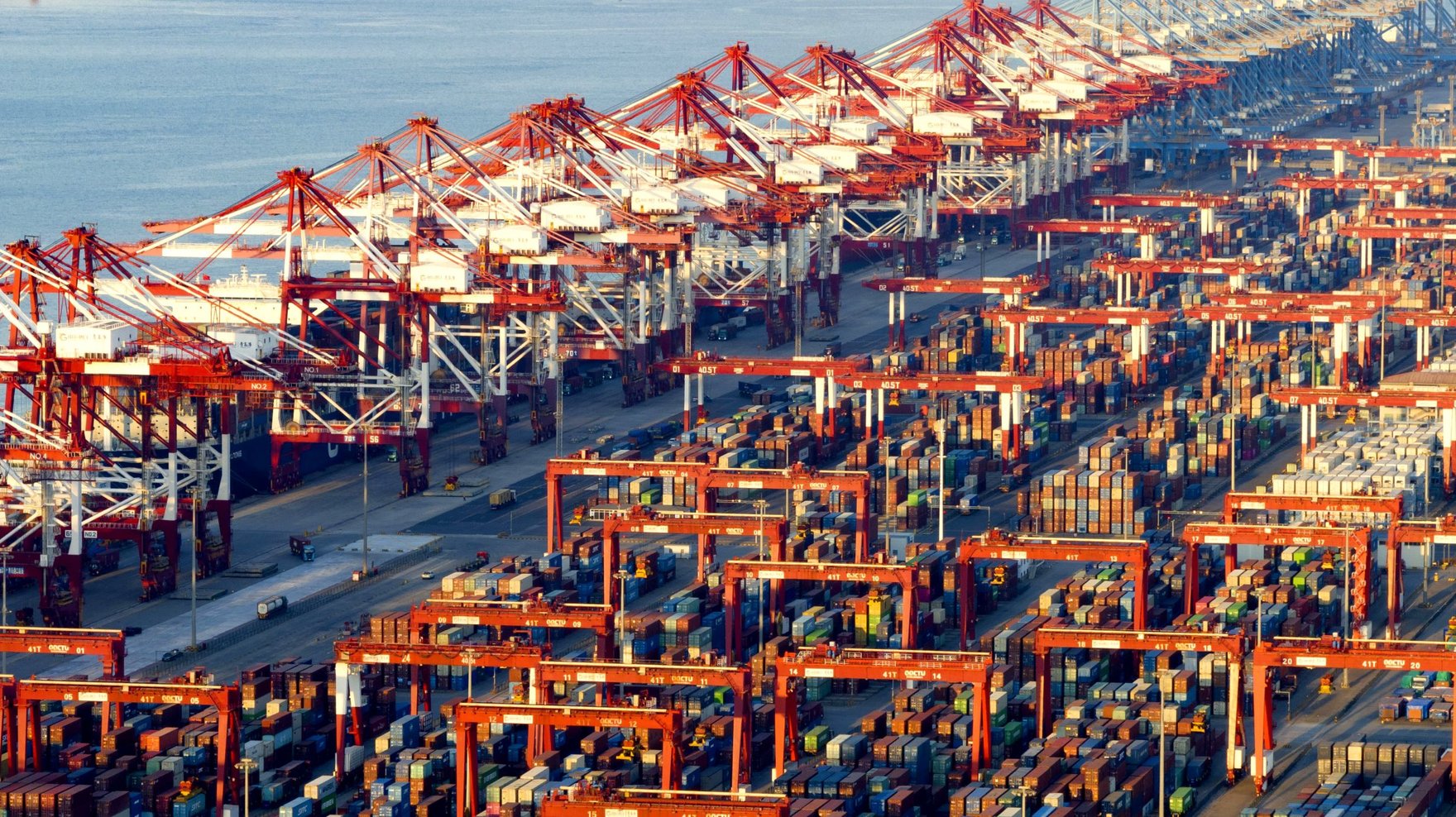

Major Chinese e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba, JD.com, Pingduoduo/Temu and Shein, along with millions of Chinese sellers on local platforms such as Amazon Europe, Allegro, TospinoMall and Mercado Libre, have expanded globally. With advantages in low-priced, high-quality, “made in China” goods, a globalized supply chain and expanding e-commerce infrastructure such as overseas warehouses, these platforms have significantly boosted the country’s cross-border e-commerce trade volume.

By 2024, the total export and import volume of cross-border e-commerce had reached 2.63 trillion yuan (about US$363 billion), double the total volume of 2019. Of this, 30 percent of transactions fell under the “Silk Road E-commerce framework.” Major Chinese companies, including AliExpress, Shein and Temu, accounted for 40 percent of global cross-border online orders in 2023. More than 120,000 Chinese companies participated in cross-border e-commerce, with 2,500 overseas warehouses established by 2024.

In contrast to its global leadership in digitally ordered trade/cross-border e-commerce, China lags behind other developed economies in terms of digitally deliverable trade (DDT).2 In 2023, China ranks sixth in DDT export and seventh in imports, with exports reaching US$207 billion — only one-third of those of the top country, the United States, which reached US$649 billion. Digital technologies and international trade have become more deeply integrated, driven by advances in big data, data centres, cloud computing, digital platforms, fintech and blockchain. China has increasingly recognized the importance of international digital trade and began working on a digital trade framework around 2019. In 2022, the Twentieth National Congress of the Communist Party of China emphasized the need to innovate and develop digital trade.

In November 2024, China completed its digital trade development framework, aiming for DDT to account for 45 percent of the country’s total service trade by 2029, and 50 percent by 2035. The framework categorizes DDT into four main areas: digital products (e.g., games, movies and cultural products); digitally deliverable services in sectors such as finance, education and health care; digital technologies (e.g., telecom, IoT, cloud computing, AI and blockchain); and cross-border data flows. The first three categories dominate DDT, while cross-border data flows remain in an “early stage” due to stringent regulations.

China has acknowledged its regulatory shortcomings in DDT and is focused on relaxing market access in key digital fields, such as telecom, the internet, cultural products and cross-border data flow regulations. To facilitate this, Beijing has established pilot zones and free-trade ports with more flexible rules, in line with high-standard digital trade frameworks in the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

China’s Strategy on Global Digital Trade Collaboration

As part of its broader digital economy strategy, China has actively sought to shape international rules for digital trade. Its submissions to join the DEPA and the CPTPP in 2021 marked a significant step in this direction. These agreements represent the “highest standards” of digital trade, with rigorous requirements on cross-border data flows, data localization, intellectual property, government procurement, market access and more.

Domestically, China seeks to promote high-level opening and economic development. Joining these agreements would create external pressure to push forward difficult reforms (e.g., regarding the data cross-border flows), similar to those faced by the country when negotiating its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in the 1990s. Geopolitically, joining these agreements would help China gain a stronger foothold in international rulemaking in the digital economy.

By 2024, China’s focus has shifted more toward technological standards for digital trade in the two agreements, such as digital taxation, electronic invoicing and payments, and digital identities, which could specifically facilitate DDT. China recognized that digital trade, especially DDT, is a crucial component of digital economy and a driving force for international trade. This recognition has been driven by the evolving digital technologies and the challenges Beijing has faced in international trade, such as decoupling in supply chains since the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, its submission to join the CPTPP and the DEPA faces significant challenges. The primary hurdle is not the complex issues like cross-border data flows and data localization — both agreements include broadly defined exceptions that make it difficult to enforce such rules — but the concerns of existing members about China’s disproportionate influence on the agreements and their shared values and norms once it joins.

Meanwhile, China has been actively shaping digital trade norms in broader fora such as the WTO and the Group of Twenty, though the latter focuses on general principles rather than specific rules and the former’s e-commerce negotiations are progressing slowly. In contrast, China’s efforts to join the CPTPP and the DEPA are essential, as they involve fewer members and higher standards.

China is also deepening digital trade cooperation with regional groupings and organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Central Asia and BRICS, which largely overlap with the BRI nations. However, digital trade growth in these regions is hindered by issues such as uneven digital infrastructure; an overemphasis on data security and data localization; lack of technological standards for digital trade, such as electronic payments and invoicing; and weak cybersecurity. For instance, despite agreements such as the “BRICS Economic Partnership 2025” and the “BRICS Digital Economy Partnership Framework,” progress on digital trade within BRICS remains slow, with only limited growth in cross-border e-commerce.

China’s evolving approach to digital trade began with the rise of its e-commerce platforms and was reinforced by its strategic initiatives, such as the DSR. While the rapid expansion of cross-border e-commerce continues, China’s approach has broadened to a more comprehensive focus on DDT, acknowledging its importance in the context of rapid technological advancement. The country’s efforts to join the CPTPP and the DEPA highlight its ambition to play a larger role in shaping international digital trade agreements and to expand its digital trade with developed economies. Although China continues to deepen digital trade cooperation with developing countries — particularly those along the BRI — such transactions remain limited due to challenges such as an overemphasis on data security concerns, a lack of technological standards, and political distrust.

This article was first published by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies.