The steep decline of the stock market since the start of February has rekindled memories of the financial crisis a decade ago. To be clear, this article isn’t a prediction piece. It’s premature to conclude that global economic recession is imminent, but it’s exactly the appropriate time to ask if the United States could handle a crash.

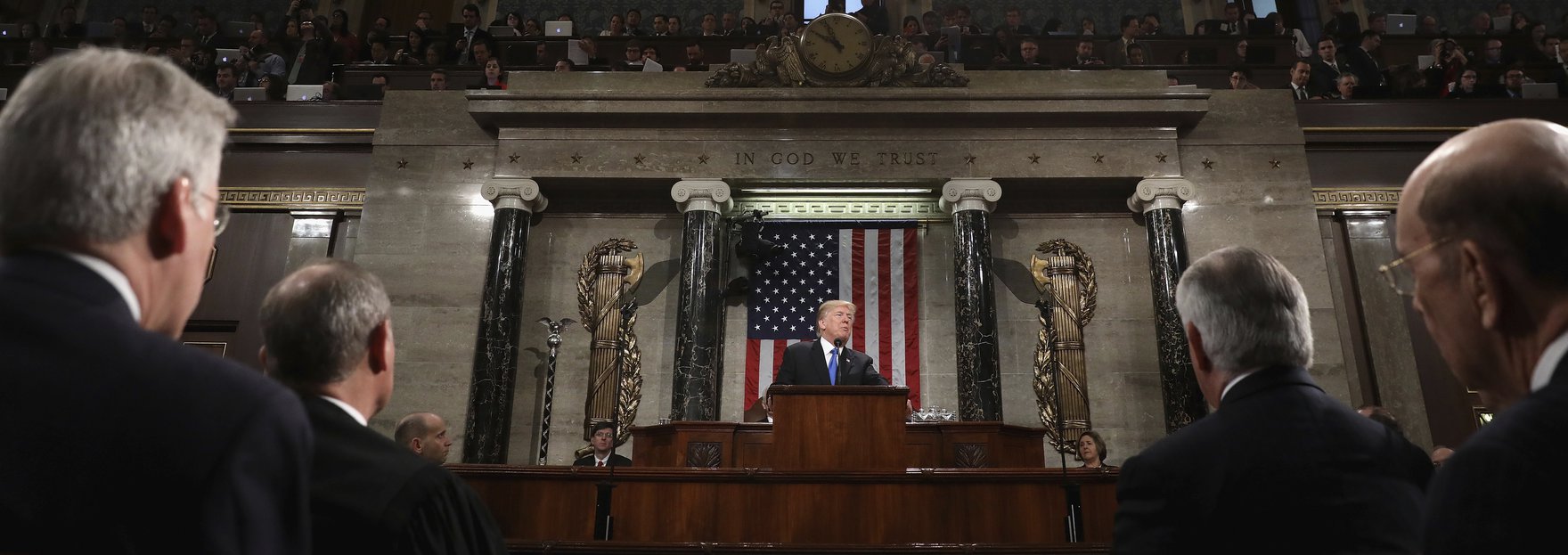

February’s economic downturn served as a nice reminder that while President Donald Trump has enjoyed a remarkably good economy, things can go bump in the night. And the timing of recent turmoil is embarrassing to the president, who, through the month of January, repeatedly pointed to the record level of the market as a result of his economic program. A new tide of optimism, he said in his State of the Union speech, was sweeping through the land.

Sensible analysts discounted the claim as utter nonsense. The market’s rise reflected expectations of lower taxes on the stream of income that firms provide through dividend payments. Markets are now waking up to the realization that what tax cuts give away with one hand, they can take back with the other, in the form of higher interest rates. With the economy at full employment, the United States Federal Reserve will likely respond to the stimulus provided by the tax cuts with higher interest rates. Those higher interests reduce the discounted value of future dividends, and thereby asset prices.

So, if the president was prepared to claim responsibility for the market’s rise in January, he should also be prepared to accept responsibility for its February retreat.

But don’t hold your breath. The past year tells us that Trump has a fraught relationship with the notion of responsibility. He is eager to take credit for successes — even when he is not responsible — and doesn’t hesitate to blame others when things go south.

This dynamic should be deeply troubling. Although the president and his advisers may eschew the responsibility, the United States retains its role as global leader. This role requires that it act as crisis manager for the global economy when problems arise. And, to be certain, problems will continue to arise. Again, this is not a prediction; it is a statement of fact.

The effects of those crises depend critically on how the United States and others respond. The danger is that, after a year of denigrating international institutions and alienating international partners, the Trump administration has eroded the stock of trust and goodwill that facilitates international cooperation.

Effective management of any global economic crisis requires competent, confident leadership — in part, because international financial markets and those who manage them are fickle advocates of independence. When asset prices are rising, they have no need for government; they are supported by a multitude of pundits, politicians and economists in a Greek chorus extolling the benefits of unfettered markets. Yet, in the midst of crisis, they make desperate phone calls to Treasury officials and central bankers to explain the need for urgent government intervention to assist financial markets and prevent harm to the economy. Assessing the validity of these arguments and calibrating the appropriate response to a crisis requires sound judgment, forged by experience and calm reflection.

These qualities are in short supply in the Trump administration, illustrating a decisive break from recent experience, in which past administrations — Republican and Democratic alike — were generally staffed by qualified people.

This fact was on display in the terrifying days following the Lehman Brothers shock in the fall of 2008 when output, employment and trade flows collapsed in a vertiginous decline. US Treasury officials responded quickly, mobilizing Group of Seven and Group of Twenty partners to coordinate the international response in an effort to restore confidence and prevent the spread of financial dysfunction. President George W. Bush — who, admittedly, is subject to manifold criticisms on many counts — demonstrated leadership by acknowledging the United States’ role as the proximate source of the financial crisis. That act of contrition gave the efforts of his Treasury officials instant credibility with their international peers and strengthened crisis management efforts.

Would the current incumbent of the White House subordinate his ego to advance the interests of the greater good? It is difficult — if not impossible — to conceive of him doing so. It’s more likely that he would react with his usual management style, best described as chaotic. Administration apologists may claim that such behaviour is entirely intentional. Intentional or not, chaos is unlikely to foster effective crisis management.

In this respect, while recent stock market gyrations are worrisome, the real risk to global financial and economic stability lies in an administration that lacks the temperament and experience to chart a course out of turmoil. Consider another case from history; in his memoirs, Dean Acheson, the highly respected Secretary of State who navigated post-war American foreign policy through the treacherous waters of nuclear deterrence, recalled the challenges faced during the early days of the Korean War. Acheson observed that the government of the day was capable of dealing with more than one crisis at a time. Unfortunately, the Trump administration likely won’t have the luxury of dealing with problems in sequential fashion — when crisis hits, one challenge spawns another.

The global economy could suffer from an the United States' untested and inexperienced administration led by a mercurial chief executive. With the economy at full employment and monetary policy at an inflection point, the danger of policy mistakes is greater than it has been for some time; recent stock price volatility reflects that. In this environment, the president’s capacity to manage crises will be tested. Once more, this is not a prediction, but a reality.