On March 10, 2020, Senior Fellow Dan Ciuriak addressed the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade regarding the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement and its suitability for the knowledge-based and data-driven economy. The following is a lightly edited version of his remarks.

Chair, Honourable Senators. It is an honour to have this opportunity to address this committee.

I should like to make three points:

- provide evidence on the quantitative impact of the agreement;

- comment on what the agreement does and does not do regarding certainty for business; and

- comment on its suitability for the emerging knowledge-based and data-driven economy.

The Economic Impact of the CUSMA

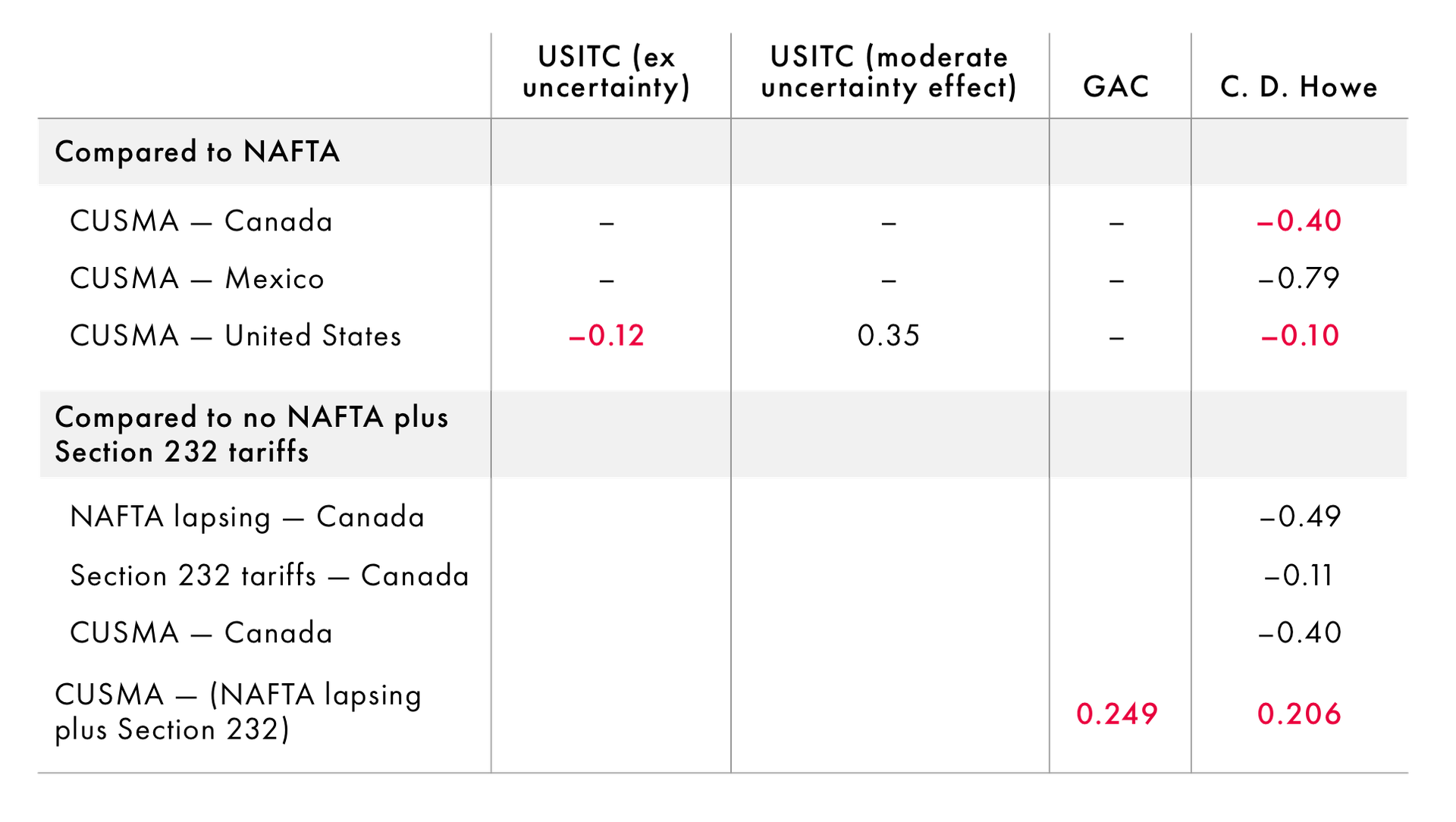

Relative to the status quo of an in-force North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), we estimate that the CUSMA produces a negative impact on the Canadian economy, lowering its GDP on a permanent basis by 0.4 percent. Relative to a baseline that includes NAFTA lapsing and US Section 232 tariffs in place, our figure is comparable to that published by Global Affairs Canada (GAC). For the United States, we obtain an estimate of –0.1 percent, which is close to the official estimate by the US International Trade Commission (USITC) of –0.12 percent.

Impact on Real GDP of the CUSMA (Percent Change)

This gives me reasonable confidence in asserting that the CUSMA has negative impacts on all three parties, both in terms of real GDP and in terms of economic welfare.

The main reason for the negative impact is more restrictive rules of origin, which induce greater trade diversion toward North American production inputs. This has the effect of making North America a less efficient production platform. The impact of this on Canada and Mexico is greater than for the United States because Canada and Mexico have a greater share of production that must comply with these new rules to sell into the United States.

Business Uncertainty

Historically, Canada’s trade shocks have come primarily from the United States, including:

- the 1866 abrogation of the Elgin-Marcy Reciprocity Treaty, which drove Canada toward Confederation;

- the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff;

- the 1971 Nixon measures;

- the frequent targeting of Canada in the post-1980 rise of anti-dumping and countervailing duty actions;

- the post-9/11 border thickening;

- the Buy American provisions adopted by the Obama administration in the context of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008–2009; and

- the Section 232 national security tariffs.

Uncertainty acts as a non-tariff barrier. The CUSMA:

- importantly, retains the binational panel mechanism for trade remedy actions;

- usefully, improves the state-to-state dispute resolution mechanism, particularly given the effective loss of binding WTO dispute resolution vis-à-vis the United States;

- unhelpfully, introduces a sunset clause that clouds longer-term business certainty; and

- worrisomely, does not restrict the use of Section 232 and other national security instruments.

On balance, I conclude that Canada faces a less certain business environment going forward than we have been accustomed to.

The CUSMA and the Emerging Knowledge-based and Data-driven Economy

Our economy is evolving rapidly due to technological change, with big data, artificial intelligence, machine learning and the looming Internet of Things promising pervasive disruption. This emerging economy is prone to market failure on numerous grounds.

There is a high degree of regulatory ferment globally in establishing guardrails for this emerging economy. Data is not treaty ready — and the CUSMA is not data ready. Rather, it seeks to lock in a favourable context for the major technology companies — a major policy objective for the United States. By the same token, it limits Canada’s ability to develop policies to prosper in this economy where value is in intangible assets, of which Canada owns precious little, and to manage its risks.

Conclusion

The CUSMA is a step backward in North American economic integration: it signals this with the absence of the words “North America” and “free trade” in its title. Its marginal impact relative to the status quo is negative in economic efficiency and welfare terms. It leaves Canada exposed to risk about future market access, which Canada will have to address through trade diversification. And it forces Canada to work within a constrained policy space to prepare for our future in the data-driven economy.

In point of fact, while the CUSMA has been billed as a twenty-first-century agreement, the twenty-first century for which the CUSMA was designed is effectively already over. Force majeure requires Canada to sign, but it is important in implementation to preserve and create as much policy space as possible to allow Canada to chart its future course in the real twenty-first century that is rushing at us.

Thank you.