Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, outlines the principles of democratic elections. In brief, these are that votes must be free and fair; human rights and fundamental personal freedoms must be respected; and the freely expressed will of the people must be reflected in the outcome.

The United States International Development Agency holds that the electoral cycle is a continuous process rather than a series of isolated events. Citizens’ trust in their electoral institutions is key to ensuring this process is not tarnished. And, as recent events worldwide have again shown, the process is never fixed. Unless democracy is continuously upheld and renewed, it can weaken or fail.

Kenya’s Complicated History with Elections

Kenya is a case in point. The country has held 13 general elections since attaining independence from Britain in 1963. With the advent of multi-party politics in 1992, Kenyan elections have tended to be highly competitive and divisive, primarily due to the organization of political parties along tribal and regional lines. General elections in 1992 and 1997 were marred by violence. In 2007, the bloodshed escalated to the worst violence yet seen in Kenya. Following hotly contested election results, more than 500,000 people were displaced, and over 1,500 were killed.

Ushahidi, the not-for-profit organization I currently lead, was born out of this crisis. It is helping raise awareness about atrocities committed during that time amid a media blackout and attempts by the government to downplay the severity of the situation. Ushahidi’s founders — Ory Okolloh, Erik Hersman, David Kobia and Juliana Rotich — created a platform enabling documentation and escalation of critical events for response.

Low Trust in Electoral Systems

While tensions during Kenyan electoral cycles are typically attributed to triggers such as ethnicity, classism and flaws in the electoral processes, mistrust seems to lurk at the heart of it all. The Kriegler Commission, formally known as the Independent Review Commission (IREC), was established in February 2008 to investigate all aspects of the preceding year’s general elections, with a specific focus on the presidential elections. It was headed by former South African judge Justice Johann Kriegler. The Kriegler Commission’s report on the 2007 elections found that electoral malpractice was too widespread across all political camps that year to determine any conclusive outcome in the presidential election. Among the report’s many recommendations were that biometric registration be adopted to support verification of voters at polling stations and that an integrated and secure tallying and data transmission system be developed, to safeguard against vote tampering and counting malpractices.

The Kriegler Commission’s report and the subsequent promulgation of a new Constitution for Kenya in 2010 introduced several changes in the electoral processes, including the enactment of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission Act and the Elections Act in 2011, and later the Elections (Technology) Regulations in 2017, among other subsidiary legislation that followed a disputed and nullified presidential election in 2017.

The 2013 general elections had been the first run by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) established by the act of the same name in 2011. Electronic technology was deployed for results reporting and transmission in a bid to legitimize the electoral process, but this largely failed, leading to delays in the reporting of results and a reversion to manual transmission of vote results.

The 2017 elections saw the introduction of the KIEMS (Kenya Integrated Election Management System) biometric voter identification system by the IEBC, to safeguard against individuals voting multiple times. However, a few weeks before the general election, the head of Information and Communications Technology at the IEBC was found tortured and murdered. The voting and counting process on election day (August 8, 2017) was generally handled well, but significant problems with electronic transmission and tabulation of results from polling stations resulted in significant delays and a lack of transparency.

The 2022 general elections saw the IEBC make massive improvements in conducting a transparent process through the use of technology. According to a pre-election observations report from the Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet), a multi-stakeholder think tank for policy formulation, several encouraging and progressive steps were made in the use of technology by the IEBC, and by the public.

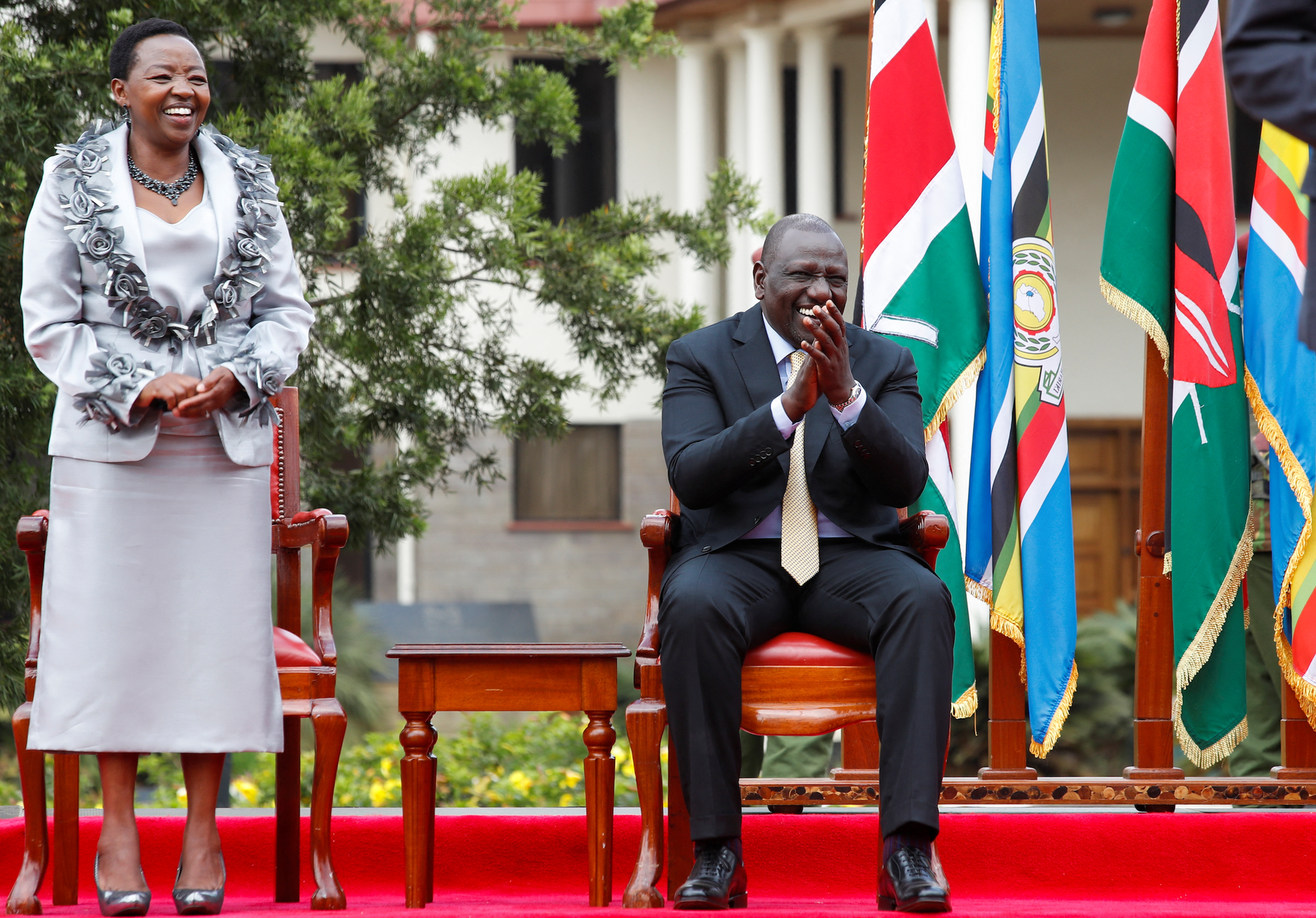

Even so, there is continuing popular mistrust in the country regarding the use of technology to support the electoral process. The basis of a Supreme Court of Kenya petition by 2022 presidential candidate Raila Odinga challenging the winning results of his opponent (now president), William Ruto, was that the results transmission system had been tampered with, a claim that the Supreme Court unanimously quashed.

As social media use has continued to grow, the battle for Kenyans’ hearts and minds has shifted online.

Social Media and the Misinformation Train

As social media use has continued to grow (from 3.6 million users in 2014 to 11.8 million users in 2022), the battle for Kenyans’ hearts and minds has shifted online. We’ve also seen a steady and disturbing increase in mis- and disinformation intended to influence the outcomes of Kenyan elections.

Indeed, in the lead-up to the 2022 elections, Kenya’s National Cohesion and Integration Commission threatened to shut down Facebook for failure to address hate speech propagated on its platform. This threat was in response to a damning report by Global Witness, an organization that challenges abuses of power to protect human rights, which pointed to the platform’s apparent inability to detect hateful ads weeks before the election. Meta responded, saying they’d hired more Swahili translators and were doing their best to take down videos violating terms and conditions.

Twitter, in the meantime, began flagging tweets that could potentially mislead the public about who had won the presidential race in 2022. It stands to reason this move was at least partly driven by pressure from civil society groups and other critics of social media platforms’ lax policing of misinformation.

TikTok has in recent months quickly expanded its reach, especially with younger Kenyans. Unfortunately, a research study by Odanga Madung, a Mozilla Foundation fellow based in Kenya, found that rather than learn from the mistakes of Meta and Twitter, TikTok in 2022 became a breeding ground for propaganda, hate speech and disinformation about Kenya’s election.

After what had been a relatively calm voting period, the disinformation machinery trained its attention on distorting the outcome of the election. Our (Ushahidi’s) election-monitoring project Uchaguzi saw a threefold increase in misinformation online between election day and when results were announced on August 15, 2022.

Building Trust and Tackling Misinformation: The Way Forward

The recently concluded general elections registered a turnout of only about 65 percent — the lowest in the past 15 years. Youth participation was equally low, with only three million of the six million new young voters registered by the IEBC showing up at the polls. Ernest Bai Koroma, a former president of Sierra Leone who was part of the African Union and COMESA (Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa) observer team, attributed the low turnout to the voters’ youth and broad lack of confidence in the political process. Three quarters of Kenya’s population is comprised of people under age 35, according to the 2019 census. And the number of voters between ages 18 and35 who registered to vote in the August polls dropped by 5.27 percent compared to 2017, according to the voters register released by IEBC in June 2022.

In a report on the recent elections, the Carter Center (a non-governmental organization that helps to improve lives by resolving conflicts, advancing democracy and preventing diseases) also faulted the IEBC — while lauding its efforts in conducting a transparent process — for failing to conduct adequate voter education to build public confidence on the deployment of technology for voter registration, verification and results transmission.

In delivering its ruling upholding candidate Ruto’s victory, the Supreme Court of Kenya also called out the IEBC’s failure to instill confidence in the electoral process, advising reforms in corporate governance of the IEBC, along with a host of other recommendations, including ensuring that servers supporting elections and those supporting internal administrative work are distinct and handled separately.

Civic education is crucial and should precede all elections. This process should also be continuous to ensure that citizens are educated on their rights and responsibilities, as well as on the best practices before, during and after the vote.

Tackling misinformation online continues to be a complicated venture. The scale of misinformation in Kenya makes it difficult for fact-checkers to keep up. And while there’s a case to be made for arming social media users with tools and skills to detect fake news, the bulk of the responsibility falls squarely on the shoulders of those whose platforms are being manipulated to spread this infodemic.

Social media platforms and media tech companies must pay closer attention to adherence to their policies and guidelines, even in markets they deem to be less relevant to their primary markets. This means investing resources to better understand local politics and how their social media platforms are being used for harm, and standing by their commitments to reduce harm and uphold integrity.

In short, the platforms must take African elections and issues much more seriously. They need to invest at least as much energy and personnel here as they do elsewhere. They must make a more concerted effort to understand the Kenyan context, and let this improved understanding inform their strategy on content moderation.

As digital solutions become part and parcel of our daily lives, we need to recognize that even the most foolproof systems may still draw mistrust. Technology has the capacity to restore trust in democratic institutions. But that trust can only be achieved if civil society prevents these new tools from being co-opted or corrupted by partisans for their own gain.

This article was produced in partnership with the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions and the Centre for Japanese Research at The University of British Columbia.