Ecuador is living through its most violent period in recent history. From January to August 2023, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported more than 4,200 violent deaths in the country. That is four times the number recorded in 2019. Just 11 days before the country’s general elections in mid-August, presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio was assassinated as he left a campaign rally. Six Colombian nationals accused of his murder were themselves killed in prison last month.

As the investigations into Villavicencio’s murder progress, the perpetrator(s) of the assassination remain a mystery for the public at large. As expected, the uncertainty proved to be the ideal breeding ground for speculation, conspiracy theories and — of course — disinformation, which has been running rampant across both online and offline media, especially in the months leading up to the recent elections. Coordinated collections of trolls, sock puppet social media accounts, bots and political influencers were purportedly involved in perpetuating falsehoods during the campaigns. These same groups are also working to stoke racism, hate and further division in the country.

The problem online in the country is particularly pointed. The parties of the candidates who appeared on the ballotage for the recent October presidential runoff accused one another of purposefully spreading and amplifying falsehoods over social media in a bid to gain the upper hand. Luisa González, the candidate from the Citizen Revolution Movement, is closely tied to exiled former leader Rafael Correa, who was well known for using digital propaganda and disinformation to threaten and stymie opposition. González herself has levied attacks upon journalists in what Reporters Without Borders has deemed a “political and institutional crisis” involving increasingly violent threats aimed at the press.

Just a few days prior to the ballotage on October 15, the Attorney General’s office released a statement assuring they had a lead related to who gave the order to kill Villavicencio. Immediately after that, Christian Zurita — Villavicencio’s replacement on the ballot — said, without showing proof, that it was someone linked to Correa, the main sponsor of González. It is now over a month since the Attorney General’s statement was released, and the Ecuadorian people are still in the dark.

In the midst of all the confusion, anger and indignation, Ecuadorians had to vote in the August 20 general elections and choose their next president in a runoff election on October 15. González lost to Daniel Noboa of the National Democratic Action party. Noboa faces stark challenges — online and off.

Social media firms are failing the Ecuadorian people. These companies’ moves to cut trust and safety teams and dial back efforts to fight coordinated falsehoods have created a (dis)informational free-for-all in the country. These reversals are likely to have further catalytic effects in 2024, a year that will play host to an extraordinary swath of more than 65 national elections. As Yoel Roth, former head of Twitter’s trust and safety, put it, “In 2024, platforms will have fewer resources in place than they did in 2022 or in 2018, and…what we’re going to see is platforms, again, asleep at the wheel.”

For the 25,000 Ecuadorians who live in Canada, a core means of accessing information about politics and public life — Facebook — no longer hosts news articles, including reports about elections. The platform’s parent company Meta recently blocked such content across the country in response to a new law requiring them to compensate news organizations whose content they have used and benefited from for years.

While the number of Canada-based Ecuadorians might seem small, their inability to access information in this election was highly problematic as their voting process was convoluted. Ecuadorians living in other countries had to vote online in the general elections for the next president as well as for members of Congress. However, the electoral authority claimed its systems were targeted by cyberattacks and thus decided to redo the elections abroad. This meant that Ecuadorians in other countries had to recast their ballots for Congress members while now only voting for the two remaining candidates. All of this was happening while Meta was effectively blocking voters from accessing verified news stories on its platforms.

To a broader point, Canada-based Ecuadorians are part of a much larger diaspora community in the country, including millions of individuals potentially eligible to vote in other countries’ elections, who won’t be able to access information on Meta’s platforms.

For Ecuadorians at home and abroad, the informational landscape is polluted with dis- and misinformation, all the while suffering through the country’s most violent year — a year that has also seen unprecedented turmoil in Ecuadorian politics and society.

Before Villavicencio’s assassination, the election was already set to be a historic one. Outgoing president Guillermo Lasso disbanded Congress and called for surprise elections earlier this year. He made this move just hours before finding out whether Congress would impeach him over embezzlement accusations. Lasso took this step via a constitutional measure known as “muerte cruzada” (meaning two-way death or crossed death). It was the first time this procedure has been used. Lasso’s decree meant that Congress had to cease its activities effective immediately, while he had roughly six months to govern through executive orders.

The results of the general elections were as unprecedented as the context leading up to them. González became the most-voted-for woman in Ecuador’s history, clinching pole position for the runoffs. Noboa, the son of Correa’s first electoral contender, was the youngest candidate to participate in a runoff election — and will be the youngest president in the country’s history. The 35-year-old was an underdog in the elections, and his meteoric rise can be attributed to, among other things, the presidential debate, which took place four days after Villavicencio’s assassination and had a record viewing audience. Both candidates, ironically enough, were members of the disbanded Congress.

Ultimately, Noboa won the presidency by a small margin, with 51.83 percent of the vote. The newly elected president will only have about 18 months to govern, as he is only tasked with completing Lasso’s term. He will face a myriad of challenges in a much distressed Ecuador: crime and violent deaths, including among women due to rampant misogyny, have skyrocketed in recent years; drug trafficking operations are expanding and permeating institutions; energy is scarce and resulting in outages; extortions and kidnappings are on the rise; and El Niño will hit soon. And the list goes on.

Ecuadorians are desperate to resolve the many issues facing their country — and verified and responsible journalism is needed more than ever.

Recent history tells us that Meta’s platforms were not originally developed with news consumers in mind. However, a huge proportion of people around the globe get informed — or disinformed — about public life through Facebook and other social media platforms.

Meta, a Hub of (Dis)Information

Of the roughly 18 million people who live in Ecuador, analysis suggests more than 15 million use Facebook. The country’s government reports that 91 percent of Ecuadorians use social media on their smartphones, with Facebook being the most popular platform. And while the use of this and other Meta platforms, such as Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp, varies from community building to sales initiatives and more, a considerable number of users do get their news through the firm’s tools.

Recent history tells us that Meta’s platforms were not originally developed with news consumers in mind. However, a huge proportion of people around the globe get informed — or disinformed — about public life through Facebook and other social media platforms. They go to these sites and apps for news because of design decisions made by the companies that own them (news feeds, trends and recommended content). For precisely these reasons, we need quality, vetted journalism in these spaces. Given their past decisions, which included and enabled user growth into the billions (and corresponding profits), social media companies have a responsibility to provide and prioritize this information, particularly during elections and other pivotal events.

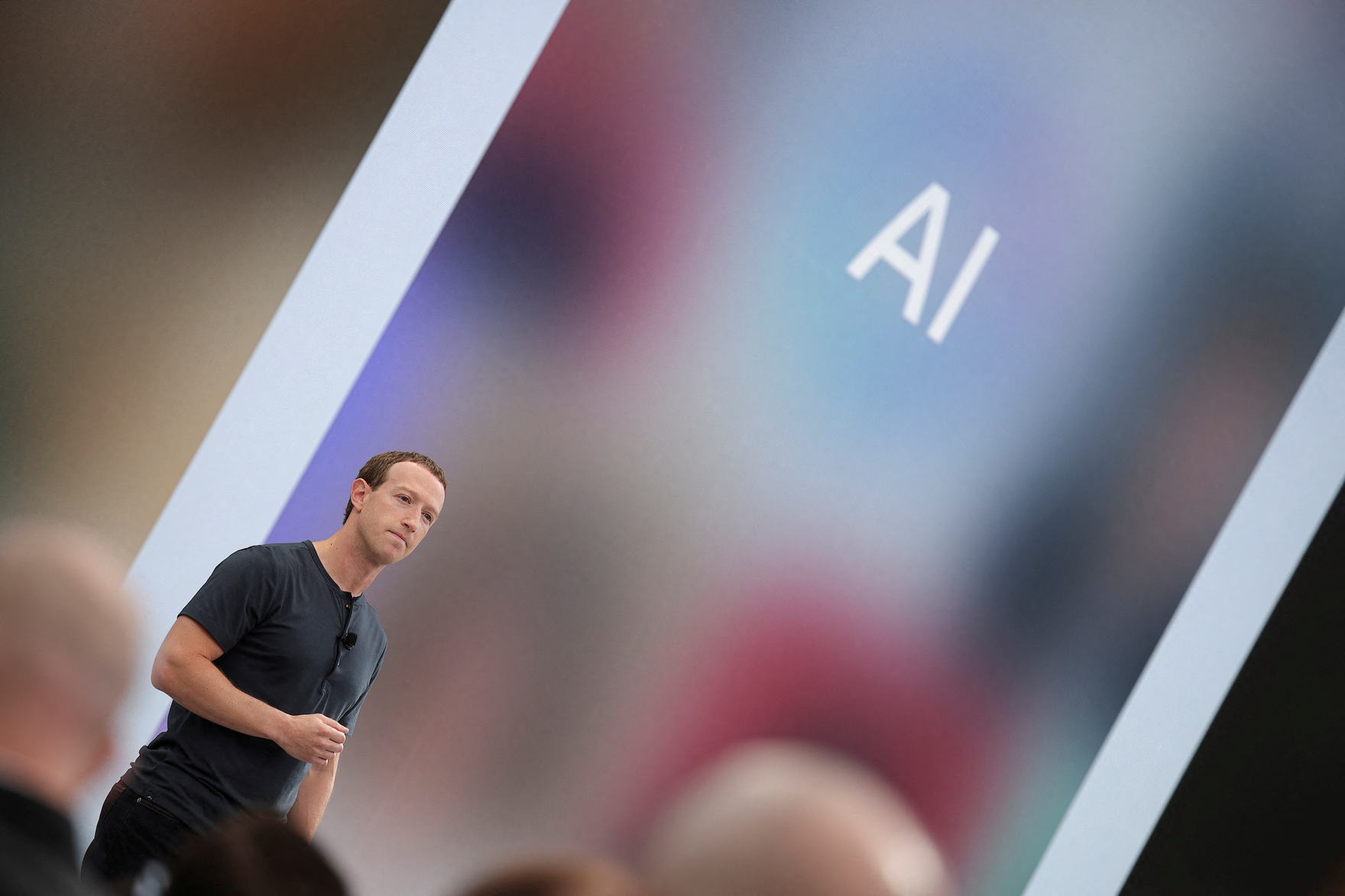

Mark Zuckerberg’s relationship to journalism and content moderation on his platform is complicated by political calculations and business strategy. He infamously told Fox News that private companies such as Meta should not be “the arbiters of truth,” implying that Meta is not responsible for the content shared on its platform, despite the aforementioned design decisions to clearly curate and purposefully direct content via algorithms and recommendations — including, historically, news content. And, of course, the Cambridge Analytica scandal — and what has now become a host of other such debacles — refute Zuckerberg’s claims. They show not only that Meta has long been aware of the disinformation littering its platforms, but also that Meta enables political campaigns — often the source of disinformation — to target users with falsehoods, coordinated hate, and other content aimed at stymying democracy and manipulating public opinion.

How does society combat disinformation and coordinated propaganda online? The answer, like the problem — and any other issue concerning the moderation of speech — is not simple. It requires a concerted, continuous effort from governments, journalists, public institutions, technologists, academics, the public and — absolutely — tech platforms. Despite this, the world’s biggest social media platforms are aggressively backtracking on the progress made in the face of these systemic informational problems. They are cowing to self-serving political efforts allegedly calling on their platforms to stop partisan censorship, but which actually amount to an effort to prioritize unfettered, amplified speech from elite propagandists over citizens’ safety and privacy.

How Did Ecuador Get Caught in the Crossfire?

Canada, along with the European Union, has worked to hold social media companies accountable. This summer, Canada passed Bill C-18, also known as the Online News Act. It requires “digital intermediaries,” such as Meta, to compensate content creators, specifically news outlets and journalists, for reproducing their content on their platforms.

In response, Facebook decided to block “content from news outlets, including news publishers and broadcasters.” When it comes to being the “arbiters of truth” and fighting endemic issues of highly strategic political disinformation, Meta has reverted to shrugging off responsibility and adopting a passive (democratically and humanitarianly irresponsible) stance. But when it comes to news media compensation and fair distribution of value, the firm blocks all news content from its platforms. So, Zuckerberg’s priorities seem to be clear. His company would rather block and censor news outlets instead of share revenue with them.

At first, it was believed that Meta would only block Canadian news sites, which would have been concerning enough. However, Meta decided to block the visibility of all news outlets for Canadians. In a press release, they labelled the move as “a business decision to comply with the Online News Act.” This “business decision,” however, ignores some key considerations.

First, a considerable number of Facebook and Instagram users, as mentioned before, get their news almost exclusively from Meta’s platforms.

Second, even though they are allowing international sites “outside of Canada [to] continue to be able to post news links and content,” people in Canada with a vested interest in international news won’t be able to access them. Diaspora communities, for example, have been clearly ignored — and directly harmed — in the making of this decision.

Third, Meta has not been clear as to what constitutes a news outlet. In Ecuador, the day after Villavicencio’s assassination, people in Canada could not view content on the Instagram pages of El Universo or Primicias, two major news outlets in the country. Expreso, El Comercio and Ecuavisa did not suffer the same restrictions on the same platform — and without clarity as to why. All five outlets, however, were blocked for Canadians on Facebook. This is a clear indication that Meta’s “business decision” is not consistent within and among its platforms. News sites in Argentina and Spain were left untouched, while publishers in Chile, Mexico and Peru were affected.

With the aftermath of the elections in Ecuador and the pending investigation into Villavicencio’s assassination — and numerous other critical elections on the horizon — the outlook for the state of news and information on Meta’s platforms and across social media is grim. Without serious, rapid action, these spaces will revert to being rife with propaganda and spam. This is bad for users and advertisers, and equally terrible for democracy. Tech firms must act now, and decisively, and we must continue to work to hold them accountable in doing so.