Donald Trump swept into office in 2024 on the promise of “America First” — a rejection of costly foreign entanglements and a renewed focus on rebuilding the American economy, industry and national spirit. His appeal rested on a vow to avoid unnecessary wars, dismantle globalist entrenchments and redirect US attention inward. For millions, Trump was the anti-war president, the pragmatic isolationist, the builder-in-chief who would restore American greatness by putting American needs above global adventures.

But Trump 2.0, as seen in his recent foreign policy stances and actions, suggests a different agenda is at play. His aggressive posturing toward Iran, bizarre embrace of Pakistan and escalating friction with allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Group of Seven (G7) are raising questions not only about strategic coherence but about personal motivations. What was once MAGA now looks more like MTGA — Make Trump Great Again.

The essence of Trump’s evolving foreign policy is not ideological consistency or strategic vision. Rather, it is the use of diplomacy, military leverage and international spectacle to centre Trump himself as a global brand. He does not aim to reshape the world order based on US national interest, but rather to project himself as its most indispensable character: the dealmaker, the peacemaker, the strongman who can bring adversaries to heel and allies to heel harder.

In this model, foreign policy becomes theatre, and Trump is always the lead actor.

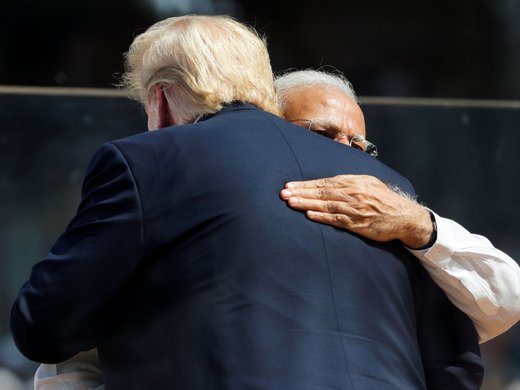

Take, for instance, his recent rhetoric about brokering peace between India and Pakistan. Trump has repeatedly claimed credit for causing a ceasefire between the nuclear neighbours. These assertions are not rooted in verifiable diplomacy but in the performative logic of reality TV politics: take the credit, own the narrative, even if it wasn’t your show to begin with. In this model, foreign policy becomes theatre, and Trump is always the lead actor.

More troubling is the apparent shift in Trump’s posture toward Pakistan. Historically a hub of strategic ambiguity, Pakistan has long been both ally and adversary to Washington. Yet Trump’s recent flirtations suggest a willingness to re-engage Islamabad’s military establishment for transactional gain. Rumours abound of covert cooperation channels being revived, not just in intelligence but potentially in frontier technologies such as digital assets. Allegations of backdoor crypto deals or political favours via opaque channels evoke a disturbing image: a foreign policy shaped less by statecraft and more by personal or familial business interests.

Trump’s business empire and business associates have already faced scrutiny over questionable real estate ventures in places such as Azerbaijan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. If similar relationships are developing in unstable but strategically useful nations, such as Pakistan, the implications are serious. Not only does this raise ethical red flags, it weaponizes the presidency for personal profit.

Meanwhile, Trump’s approach to long-standing US allies is increasingly antagonistic. He routinely disparages NATO, questions defense commitments and levies tariffs against G7 partners. These acts are not part of a larger doctrine of rebalancing global power but seem driven by a desire to dominate headlines and dictate terms. Trump wants to be seen as the man who bends Europe to his will, not as a steward of alliances built on shared values and mutual trust.

This behaviour poses a problem for his core political base. Many of the voters who backed Trump for a second term did so out of a belief that he would withdraw America from costly global misadventures and focus on domestic renewal. But now, they see a president increasingly embroiled in foreign dramas, often of his own making and sometimes with alarming opacity. The promise to “end forever wars” is being replaced with strategic ambiguity and transactional engagement, not far removed from the very behaviours he once condemned.

Indeed, Trump’s foreign policy is neither isolationist nor interventionist. Even on matters such as China, Iran or Ukraine, Trump shifts stances with dizzying speed. It is a strongman foreign policy, but one that serves the man and keeps him at the centre of it, not the state.

This emerging Trump doctrine undermines both America’s credibility and its strategic coherence. It tells allies that they are disposable and adversaries that they can cut deals if they flatter him. It also fractures the very nationalist base that once powered his ascent. The America First movement wanted sovereignty and not a reality show spectacle for presidency. As Trump continues to entangle himself in opaque foreign dealings, he risks alienating the movement he once championed.

In the end, what we are witnessing is not the revival of American greatness on the global stage but an attempt of a man to use his presidency to solidify his personal brand using the levers of US power. This is not the foreign policy of a republic, but the marketing strategy of a man who seeks not to lead the world, but to headline it.