The sudden emergence and then rapid spread worldwide of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is shaking the foundations of the Canadian (and the global) economy in ways that will reverberate for decades. The COVID-19 virus does not treat everyone equally: pre-existing health conditions, socio-economic vulnerability, marginalization and discrimination, and precarious or poorly paid work all factor into individuals’ exposure to the virus and their likelihood of surviving it if they’re infected. Among the most economically vulnerable workers are those who own or work in small businesses. Small firms with fewer than 50 employees, razor-fine profit margins and a reliance on face-to-face interactions are at risk of immediate and permanent closure.

While the Canadian federal and provincial and territorial governments grapple with the scope and scale of assistance to these firms, a broad set of tools are being brought to bear in the short term. For example, the Government of Canada partnered with the Canadian Chamber of Commerce to create the Canadian Business Resilience Network, which aims to collect and coordinate resources that will support businesses as they navigate and recover from COVID-19. Currently, those resources include tax deferrals, direct financial support (in the form of short-term wage subsidies for qualifying businesses, charities and not-for profit organizations and temporary income support for affected workers) and access to loans and lowered interest rates.

But the short term is not all that matters. While we are still in the thick of COVID-19’s spread and our emergency response, this crisis brings into focus the need for a careful consideration of longer-term transformations that may ripple out after 2020. Is our goal simply to build back what we had, which arguably left us deeply vulnerable to such a shock, or to “build back better”? We can expect there will be a powerful psychological and political pull back to a sense of “normalcy,” a retreat to the familiar. We may be pushed to ignore the deep fractures in our social contract and economic system that left so many exposed and vulnerable. Even so, this pandemic has created an opening to reimagine our communities, and examples, models and promising experiments abound that may point the way to a more sustainable, equitable recovery.

Deeply sustainable small businesses — those that place environmental or social value at the core of their business model and vision, at a level on par with (or even ahead of) growth and profit — can teach us important lessons about the ingredients of resilience, justice and ecological integrity in Canadian communities. If these lessons can be incorporated into our evolving small business rescue plans, there may be some good among the lasting effects of the COVID-19 crisis on this crucial sector.

A large and growing number of businesses are taking steps to reduce their resource consumption, producing goods and services with a smaller environmental footprint. But making a fundamental shift toward pathways that can both limit global warming to less than 2°C above pre-industrial average temperatures and address growing social inequalities (for instance) is another task altogether. This shift requires an evolution in values, and an adjustment in the underlying logic of a firm. Some deeply sustainable small businesses focus more on collaboration than on competition, sharing new tools, methods or resources to advance their sector or community as a whole and seeing success as a collective effort. Some businesses prioritize resilience over efficiency, support the cultivation of local supply chains, offer living wages and include disadvantaged, vulnerable or marginalized workers. As radical as it may seem, these firms focus on sharing, ensuring the quality of their product over its quantity, preserving time for leisure and community engagement, and supporting the autonomy and health of workers over growth-at-any-cost.

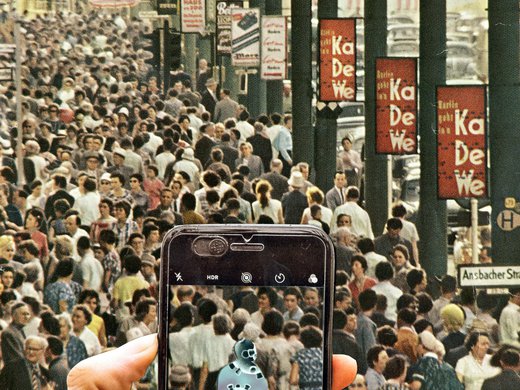

Digital technologies may play a central role in accelerating a just and sustainable recovery from COVID-19 and also in the longer transition toward the low-carbon, resilient future that could follow. For instance, as we are seeing in sharp relief during this time of physical distancing, social media and video conferencing — from video consults with a physician, to therapy sessions, live concerts and poetry readings — offer a measure of connectedness without movement. In some cases, these technologies enable a barter system — for example, professors have begun to offer to trade video guest lectures with each other, opening up the possibility that students will have access to, say, the author of their textbook, or a leading expert on any topic, to enrich their learning. This exchange may offer such benefits that it will continue after the crisis abates.

The current dramatic shift we are making in Canada to prevent the spread of COVID-19, one that forces many of us to rely on online purchasing and touchless delivery, is unlikely to benefit small firms. In many cases, new habits are being developed in favour of large corporations that already have the logistics and supply in place (such as Amazon) rather than local small businesses. Steps must be taken, supported by municipalities, provinces and the federal government alike, to rescue rather than erase local economies. Logistical support, enhanced communication and marketing, and collaborative, community-oriented approaches to meeting our needs will be central to this rescue.

In a recent Vox piece, David Roberts, who writes about energy and climate change, said that COVID-19 recovery efforts need to be big, lasting and focused on making the economy better. Governments need to use reopening as the chance to make a just, green transition to operating with more resilient businesses that provide social and environmental good. Such changes occur at the core of the business — the business model — not through slight tweaks to the resource efficiency. Grants, not loans, are needed for small businesses — and these grants need to be laser-focused on deep decarbonization and sustainable transitions. That focus doesn’t mean that businesses should be excluded if they are high emitters, or unable to make deep changes immediately. What it does mean is what we want — when we get through this — is a healthier, more sustainable, more resilient economy than we had before.