I have just returned from Asia where the ongoing financial and economic crises gripping Europe and the U.S. seem distant. Hong Kong, in particular, celebrates its role as a conduit for the steady and determined opening of China’s capital market and the so-called "internationalization" of the renminbi. Moreover, the economy continues to grow at a healthy pace. Yet, policy makers in the region are growing increasingly concerned about the slowdown in the U.S. economy and worries over the possible break-up of the euro.

The potential for future inflation is also on the minds of policy makers in the Asia-Pacific region since some are convinced that, sooner or later, both the U.S. and the euro zone will resort to inflation to ease their mounting debt burdens. Even Germany, consistently hawkish when it comes to inflation, has admitted that a little more inflation may assist in helping the euro zone ease out of the crisis. Jens Ulbrich, head of the Bundesbank’s economics department, told the finance committee of the German parliament in early May that Germany is likely to have inflation rates “somewhat above the average within the European monetary union” in the future and that the country might have to tolerate higher inflation for the sake of rebalancing within the euro zone.

Amid all the talk about Greece and Spain, not to mention Italy, it may be worth exploring the experience of two economies which, for very different reasons, have known “internal devaluations”—Hong Kong and Latvia. Are there lessons for Greece and Spain? Recall that an internal devaluation is precisely what Germany is asking Greece and Spain to undertake.

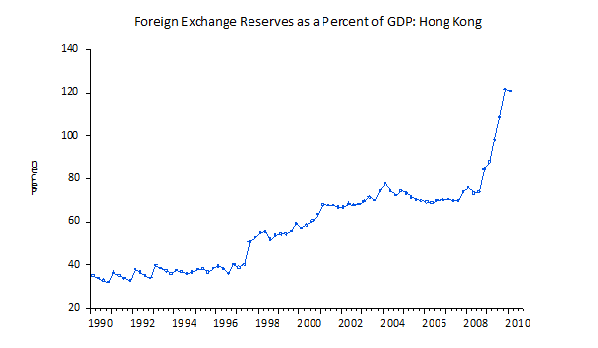

Hong Kong has long maintained a fixed exchange rate against the U.S. dollar for decades. Even during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, as other Asian economies devalued or allowed their currencies to depreciate against the dollar, the Hong Kong dollar remained fixed against the US dollar in spite of enormous pressure from global financial markets. Indeed, one of the lessons learned from the crisis resulted in a determination to build-up foreign exchange reserves to prevent any future threat to the fixed exchange rate. As shown in the Figure below reserves as a percent of GDP in Hong Kong now exceeds 100%, a feat that is virtually unmatched by most economies around the world.

Source: IFS CD-ROM (Washington: International Monetary Fund)

Of course, the rise in foreign exchange reserves holdings is also a consequence of the fixed exchange rate regime. Hong Kong’s shift from manufacturing to a shipping and finance powerhouse along with a stable legal system combined with proximity to the Chinese economy has helped promote strong economic activity relative to the U.S., whose currency the HK dollar was tied to. As interest rates in the US began to drop during the global financial crisis, the incompatibility between strong growth in HK and low interest rates in the U.S. implied even stronger growth in foreign exchange reserves holdings.

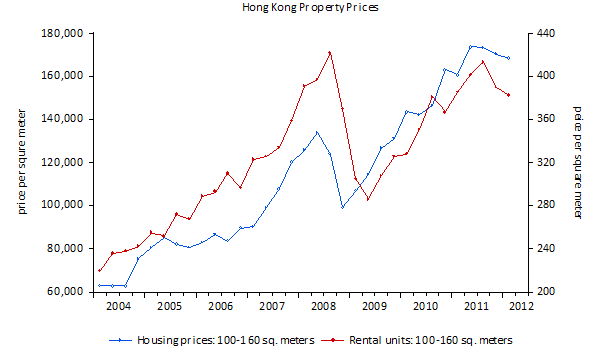

Another reflection of the impact of tying one’s hand to the economic fortunes of the U.S. is revealed in property prices. These represent the principal channels through which pressure to maintain the fixed exchange rate is relieved. As shown below, there inexorable rise has only been temporarily interrupted by the impact of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009.

Source: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/

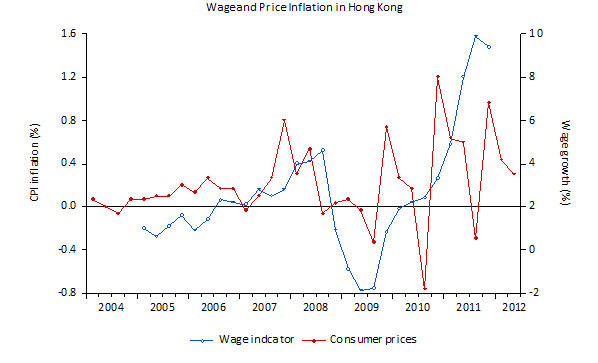

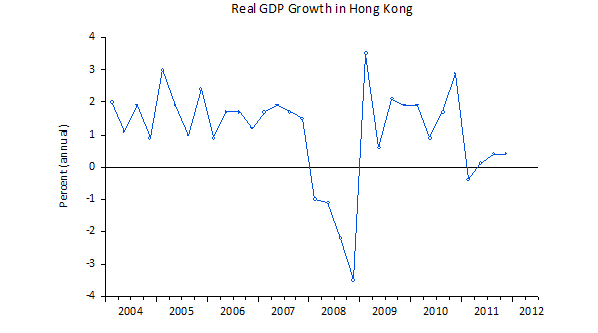

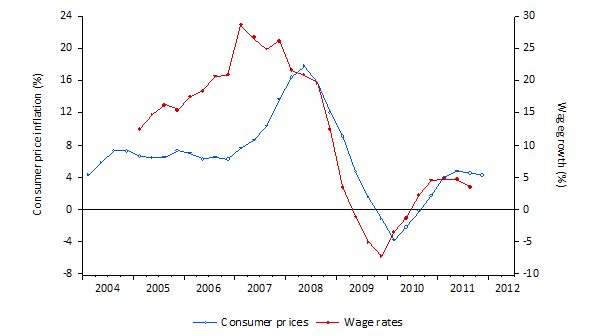

In addition, the consequences of fixing the exchange rate against the U.S. dollar, effectively just one step away from using the U.S. currency, is also evident in the impact on inflation and real economic growth. As the global financial crisis unfolded the fixed exchange rate implied for Hong Kong deflation and an “internal devaluation,” meaning that wages and incomes had to fall to maintain the peg against the U.S. dollar. Therefore, since 2008 there have been periodic bouts of deflation in consumer prices while wages experienced a compression over approximately a two year period.

Source: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/

Not surprisingly, economic growth also took a hit but the recession, although sharp, was short-lived as seen in the Figure below. And the government continues to maintain a surplus.

Source: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/

Hong Kong of course is well known to have a flexible labour market and the prospects for a prolonged recession were low given its proximity and economic links to mainland China. Unfortunately, few economies around the world can claim to have conditions such as those that prevail in Hong Kong.

A different illustration is offered by the case of Latvia. It is one of the recent EU member states which, like the others in central and eastern Europe are committed to one day adopting the euro. Requirements for joining the single currency include a commitment to meet the Maasricht convergence rules. This includes maintaining a relatively fixed exchange rate against the euro for over two years without devaluing its currency. The Latvians have accomplished this feat in spite of the heavy economic costs entailed. Indeed, the same Latvian government that imposed harsh economic measures to ensure that Latvia join the euro area in 2014 has been re-elected and, remarkably, there has been relatively little social unrest. According to the European Central bank’s latest Convergence Report (May 2012, http://www.ecb.int/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120530.en.html) Latvia meets all the Maastricht economic requirements for euro area membership.

This is unlike Greece and Spain where measures required to remain in the euro area are being resisted, governments have been thrown out of office following recent elections and social unrest is rising. Nevertheless, the economic costs to Latvia have been very large. As shown in the Figure below the disinflation and negative wage growth have been sizeable, although temporary, phenomena.

Source: International Financial Statistics (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund)

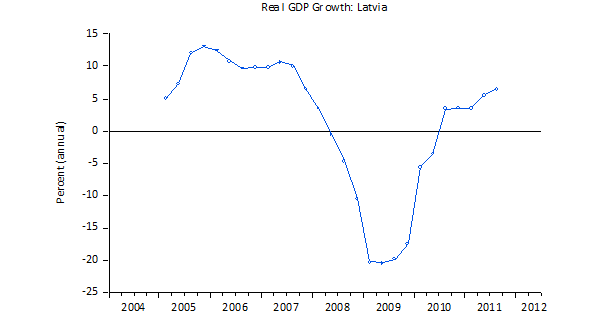

And the economic costs have been exceedingly large as seen in the development of real GDP growth shown below. Here too, like in the case of Hong Kong, but on a much larger scale, the recession in Latvia was relatively short and the rebound strong. Unfortunately, as explained above, the conditions that permitted Latvia to undertake the internal devaluation are not present in either Greece or Spain. However, both Spain and Greece have something that Latvia does not, namely they are both already in the euro zone. Aside from the economic restructuring or re-balancing that will be required is the political element vis-a-vis Germany that will be decisive in both cases. More on this in my next post.

Source: International Financial Statistics (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund)