In the span of just a few decades, the universe of money and financial assets has exploded. Once dominated by coins, banknotes and bank deposits, the landscape now stretches into digital and virtual assets — from central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and tokenized deposits to stablecoins, cryptocurrencies and tokenized real-world assets. Understanding this ever-growing spectrum is no longer simply an academic exercise. It is essential in order for policy makers to design regulations, for banks and fintechs to build the future of payments, and for investors to navigate the opportunities and risks of a rapidly digitalizing financial system.

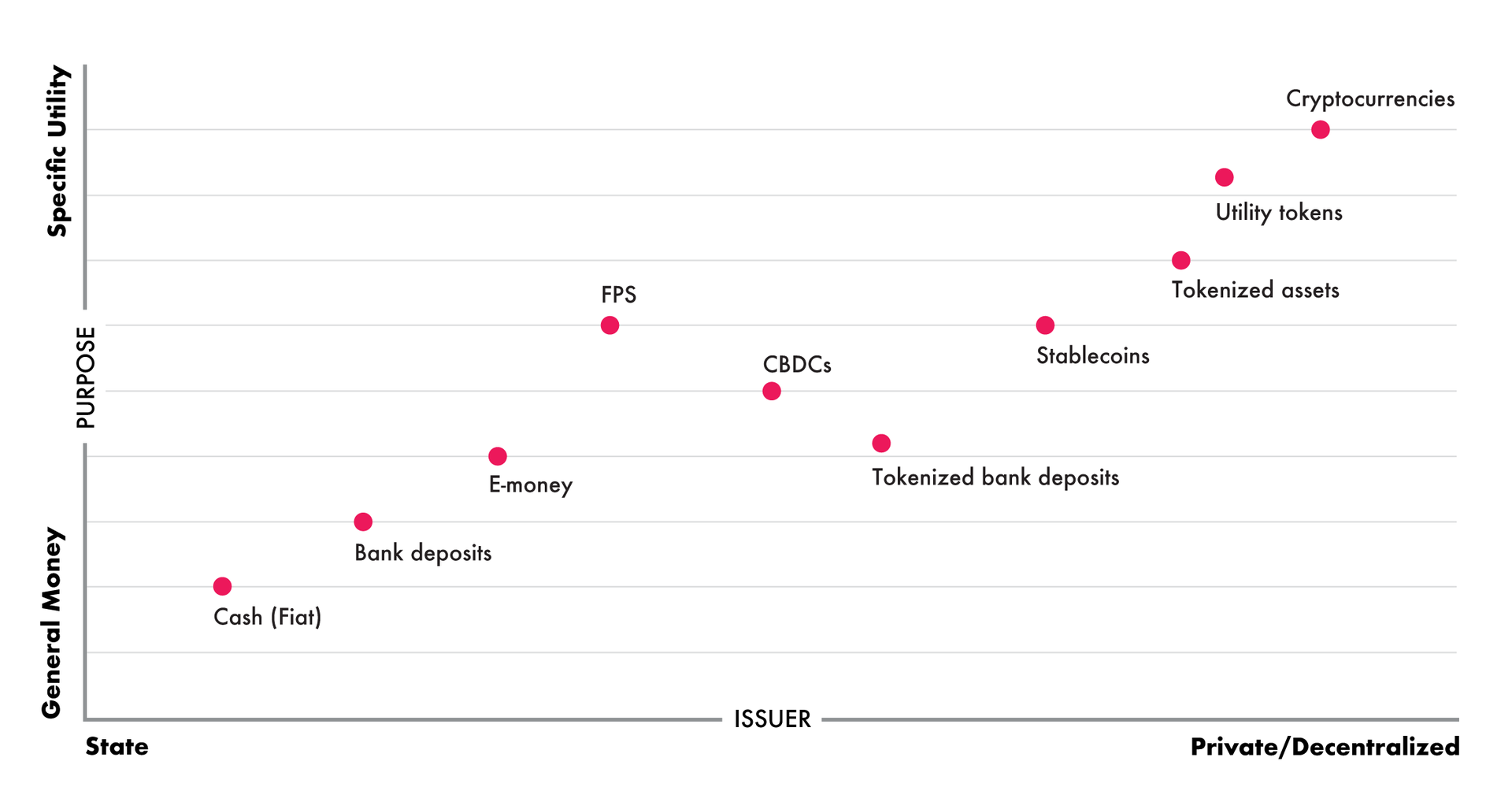

This universe of assets and currencies can be visualized along two axes. On the horizontal axis is the issuer spectrum: from state-issued money on the left to private or decentralized issuance on the right. On the vertical axis is the purpose: from general-purpose money at the bottom to specialized utility at the top. Cash and CBDCs sit near the lower-left corner, representing state-issued general-purpose money. Cryptocurrencies and niche tokens cluster in the upper right, reflecting private, often decentralized, issuance with more specific utilities. In between, we find hybrid functions such as stablecoins, tokenized deposits and tokenized assets.

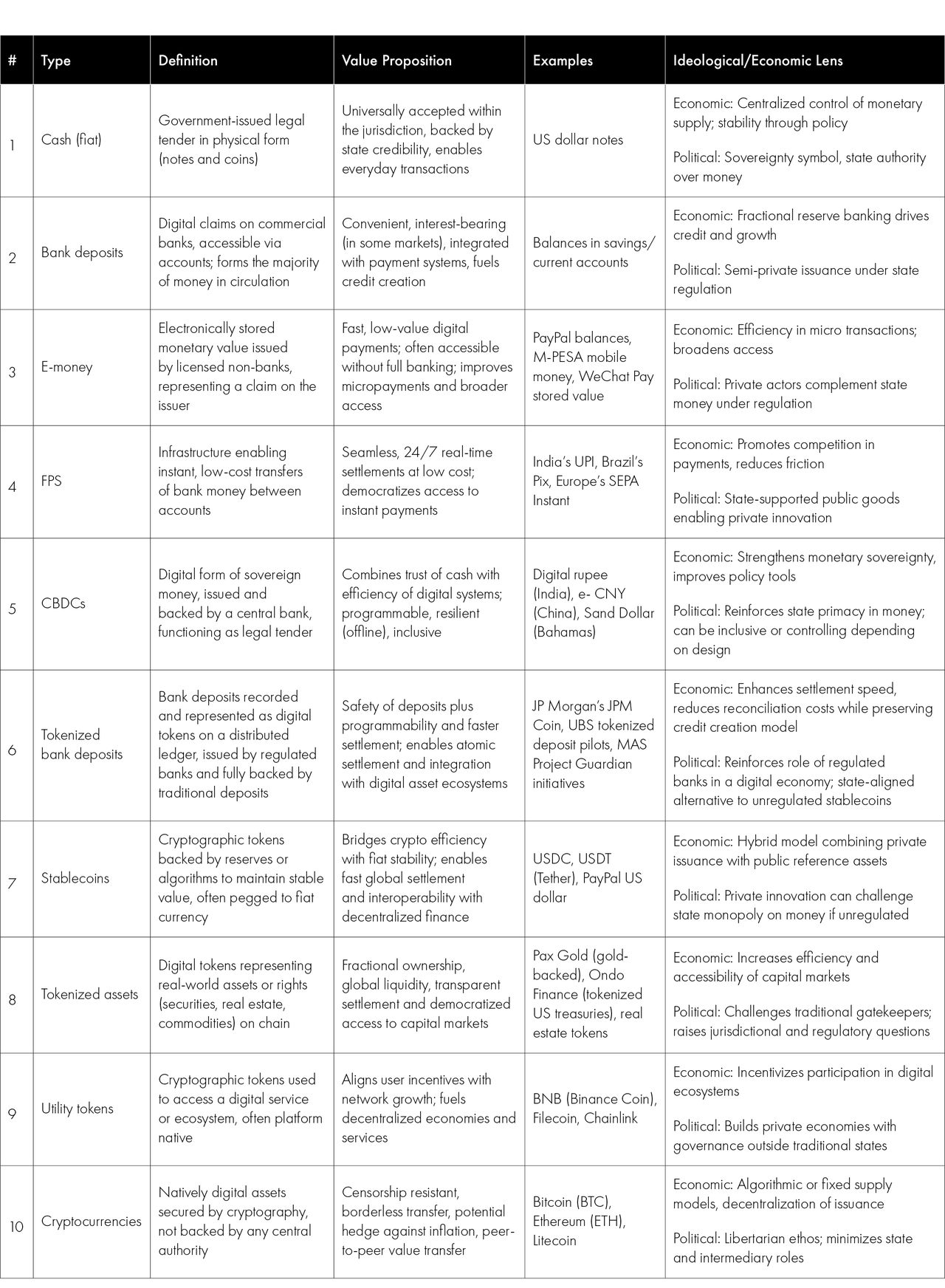

At one end of the spectrum lies traditional sovereign money. Physical fiat — banknotes and coins issued by central banks — is still the most tangible and widely trusted form of money. It is universally accepted within a jurisdiction and represents the authority of the state. Closely related are commercial bank deposits, the digital claims you hold in chequing and savings accounts. These are technically liabilities of private banks yet are fully regulated and convertible into cash. Economically, they form the backbone of credit creation and payment systems; politically, they balance private issuance under public oversight.

Layered onto these traditional foundations are digital forms of value. One variation is e-money: prepaid balances stored electronically, often by licensed non-banks. Think of services such as M-PESA in Kenya or PayPal globally. E-money expands access to payments for those without full bank accounts. Alongside this sits another innovation: fast payment systems, or FPS. These are infrastructures that allow instant bank-to-bank transfers at a low cost. India’s UPI and Brazil’s Pix are classic examples. Though not new forms of money themselves, they redefine the speed, cost and convenience of moving value.

CBDCs occupy a special space in this ecosystem. They are digital forms of sovereign money — direct liabilities of the central bank. Unlike bank deposits or e-money, they are not just claims on an intermediary; they are themselves the money. CBDCs promise the efficiency of digital transactions combined with the safety and trust of state-issued cash. India’s digital rupee pilots, China’s digital yuan (e-CNY) and the Bahamas’ Sand Dollar illustrate how countries are testing CBDCs to strengthen inclusion, enable programmable payments and ensure monetary sovereignty in a rapidly digitalizing world.

Money is no longer just cash in your pocket or numbers on a bank screen. It is becoming programmable, borderless and contested.

Between state-issued money and fully decentralized crypto-assets lies another fascinating category: tokenized bank deposits. These are traditional deposits represented as tokens on distributed ledgers, issued by regulated banks. They combine the safety of existing banking systems with the programmability and efficiency of blockchain infrastructure. JP Morgan’s JPM Coin and the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s Project Guardian are examples of how financial institutions are exploring this space. Economically, tokenized deposits could reduce settlement costs and unlock new efficiencies. Politically, they reinforce the role of regulated banks while offering a state-aligned alternative to unregulated private tokens.

Then there are stablecoins, which are digital tokens pegged to a reference asset, usually fiat currency such as the US dollar or the euro, but exist and move on blockchain networks. Stablecoins are generally issued by private entities. They bridge the benefits of crypto (speed, borderless transfer, low transaction cost) with the stability of traditional money. Tether (USDT) and Circle’s USDC are dominant examples. While they can provide a useful service, they also raise regulatory questions. Should private companies be allowed to issue instruments that mimic state money? Stablecoins highlight a core tension between innovation and oversight.

Beyond payment instruments, tokenization is transforming capital markets. Tokenized assets can represent real-world assets such as securities, real estate and commodities on a blockchain. For instance, Pax Gold offers digital tokens backed by physical gold, while Ondo Finance has pioneered tokenized US treasuries. This approach enables fractional ownership, global liquidity and transparent settlement. Economically, tokenization can make capital markets more accessible; politically, it challenges traditional gatekeepers such as central securities depositories and raises questions of jurisdictional control.

On the more experimental side of the spectrum are utility tokens and cryptocurrencies. Utility tokens are native to specific crypto platforms, such as Filecoin for decentralized storage or Binance Coin (BNB) for corporate transaction discounts. They are not designed to function as general money but as access keys or incentives within digital ecosystems. At the farthest edge lie cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH): highly decentralized, censorship-resistant and ideologically rooted in reducing reliance on governments and intermediaries. But, as they have evolved, these cryptocurrencies have increasingly been used for speculation and digital collateral rather than for regular financial transactions given the high cost of transactions. They represent a libertarian vision of money, one that exists beyond borders and state control.

Why does this mapping matter? Because each category carries its own economic logic and inherent political ideology. Cash and CBDCs reinforce sovereign control and inclusivity. Tokenized deposits and stablecoins can drive efficiency while testing the boundaries of private issuance. Tokenized assets can democratize access but disrupt regulatory norms. Cryptocurrencies can challenge the foundation of state money. And through it all, fast payment systems and e-money can improve the pipes that connect these instruments.

For policy makers, this spectrum reveals both opportunity and risk. It shows the need to innovate without undermining stability, to regulate without stifling progress. For investors and businesses, it highlights new models for value creation and transfer. And for citizens, it underscores a simple truth: money is no longer just cash in your pocket or numbers on a bank screen. It is becoming programmable, borderless and contested. The world of money is no longer binary. It is a vibrant continuum stretching from centuries-old coins to cutting-edge cryptographic tokens. By understanding this spectrum — its definitions, value propositions and underlying ideologies — we gain a clearer view of the future of finance and our place within it.