It’s fire season again in British Columbia, and the village of Lytton has been in the headlines recently, first for breaking all-time Canadian heat records, and then for, tragically, being burnt to the ground in a wildfire.

Given how hot it had been, and how dry the landscape was, fire wasn’t a surprise. In the aftermath of the recent “heat dome” phenomenon, numerous lightning strikes and human-caused fires have occurred across British Columbia.

People died in the fire in Lytton, and the speed with which it started and spread caught everyone by surprise. It’s a minor miracle that so many people managed to escape the inferno by driving away through the flames at the last minute.

In Vancouver and elsewhere in the province, hundreds of people, mostly in housing without air conditioners, couldn’t escape. They died because of the heat. On the coast, the heat killed vast numbers of shore-based sea creatures; the cost to nature has been severe.

By any standards this number of deaths counts as a major disaster. But it’s one in which visual images in the media are of the burnt town, rather than the faces of the hundreds of people who died of the heat, alone and mostly out of sight. Their deaths didn’t involve anything infectious. Perhaps, like the large numbers of people dying from opioid overdoses, heat stroke victims don’t count as worthy of priority attention?

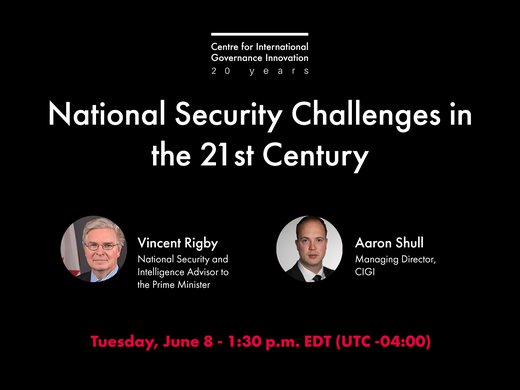

The lack of preparation to deal with extreme conditions suggests governments aren’t thinking about what it means to make Canadians secure in these new circumstances. National security is supposedly the priority for governments today. But national security clearly hasn’t included any provision for the victims of heat stroke.

Yes, there are new interprovincial arrangements to coordinate fighting wildfires, and the Canadian Armed Forces have lent transport aircraft to help. But cooling centres, neighbourhood public health systems to keep an eye on elderly or sick people, and effective warnings and instructions on how to keep cool are clearly inadequate.

Doesn’t this disaster rise to the level of a major failure of national security? Apparently not, because unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, it doesn’t seriously disrupt the economy, or the operation of government institutions.

Doesn’t this disaster rise to the level of a major failure of national security? Apparently not, because unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, it doesn’t seriously disrupt the economy, or the operation of government institutions. Hundreds have died, but for everyone else it’s business as usual.

Over the past few months there have been numerous protests by climate activists and people trying to slow or stop the logging of what little old-growth forest is left in British Columbia. This matters, in part, because intact forests can provide refuge from the heat, and absorb at least a little of the carbon dioxide that is exacerbating climate change. Protesters have also been objecting to the large subsidies that the BC government has been giving to fossil fuel companies and to those building gas infrastructure in the province.

There is a major failure of governance in the disconnect between rhetoric about climate and public safety, as well as between Canada as a supposed climate change leader and our laggard status in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We are the worst performer among our Group of Seven peers, as our new advisory council on getting to carbon net-zero has just reminded us in its initial observations on the Canadian scene.

While many Canadians take comfort in arguments that our forests act as carbon sinks, absorbing some of our emissions, as climate change accelerates and forest fires grow in scale and intensity, many forests are emitting more carbon dioxide than they are absorbing. New research from Brazil suggests that this may be the case even in the Amazon rainforest, which has often been called one of the lungs of the planet.

The carbon dioxide emissions from the fossil fuels we export aren’t counted against our tally; they count abroad, so that is someone else’s problem. If our exports add to the fuels available for burning elsewhere that make climate change worse, that, too, apparently isn’t our responsibility.

That these exports are contributing to climate change is obvious, and the source of immense frustration to numerous climate activists who don’t buy the geographical sleight of hand that is used in carbon emission calculations. Keeping carbon in the ground, wherever it is, here or abroad, is essential to slowing down climate change and allowing all of us to adapt better to these new conditions.

The costs of our narrow focus on our own backyard and the failure to connect the dots between climate change, fossil fuel use and deforestation, as well as of our discounting of the emissions from fuels we export, are adding up. The consequences of climate change are coming back to bite us, as the deaths in Vancouver should, but apparently don’t, remind us.

These choices add up to a dramatic failure to think about security and governance in a more comprehensive way. This we need to do, and quickly, if Canadians are to be kept safe. Traditional notions of governance are seriously out of date. In particular, the meaning of national security needs to be overhauled and updated for the new, more dangerous circumstances in which we now live.

Through the last few decades Canadians have used much more than their share of fossil fuels. It’s time to think long and hard about how to build a better and safer economy. That’s what the net-zero goal is supposed to help us accomplish.

But haste is essential. Hundreds of people died in the heat in British Columbia. The rest of us are also running out of time on the climate problem.