This article was first published by the Toronto Star.

We are told that we are experiencing a global mental health crisis.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), some common conditions, such as anxiety and depression, increased by 25 percent in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, adding to the estimated nearly one billion people already living with mental disorders worldwide. The WHO reports that globally, one in seven 10-to-19-year-olds suffer from a mental health disorder, and suicide is the third-most common cause of death in 15-to-29-year-olds.

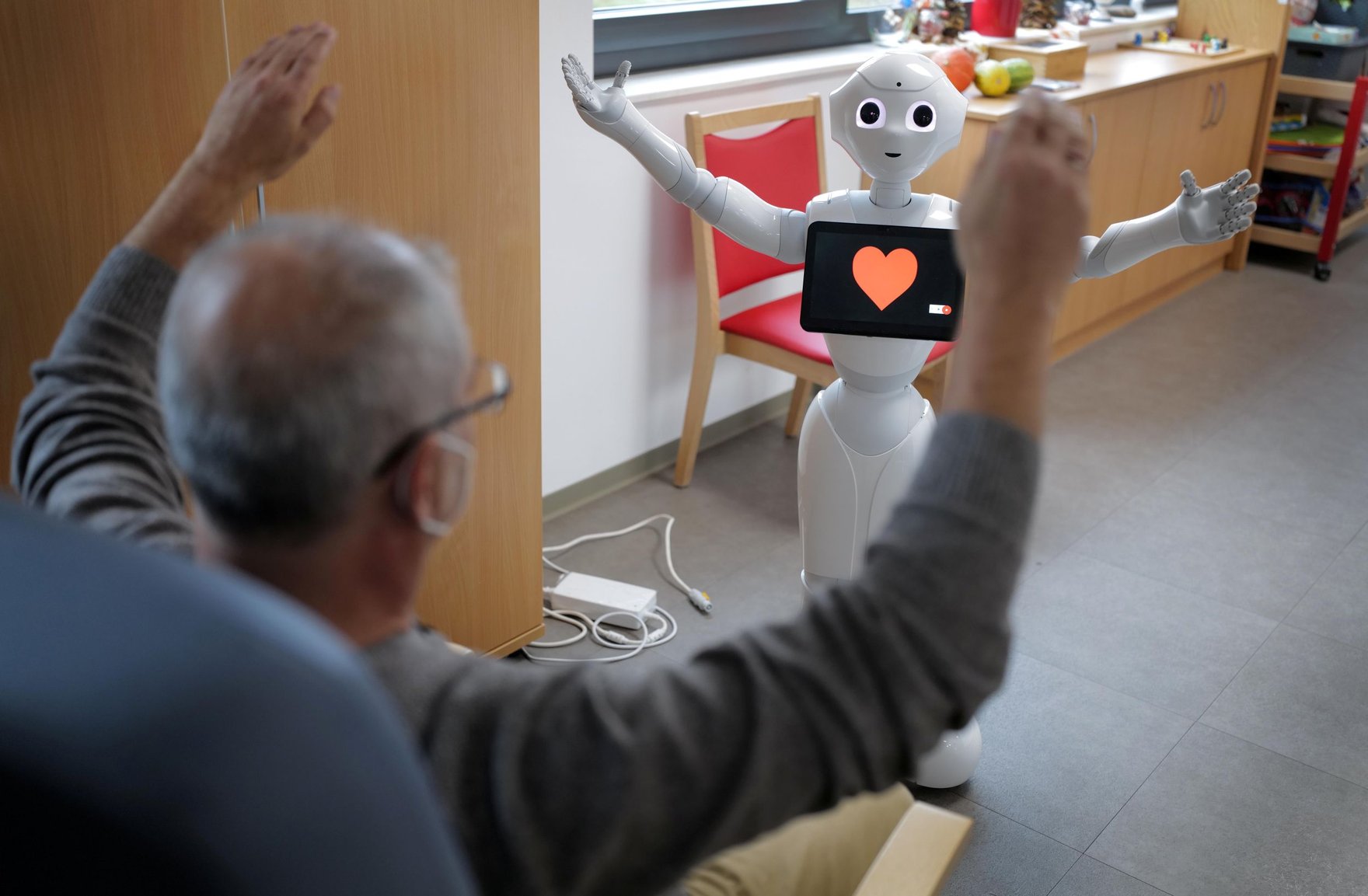

Some experts point the finger at the rise of the ubiquitous tech in our pockets, promising connection while driving division. But technology companies are already harnessing techno-optimism to sell us a tech solution to this crisis.

Recent clinical research shows that a carefully developed artificial intelligence (AI) therapy chatbot may result in positive outcomes for some patients, with 51 percent of participants with depression reporting improvement in their symptoms after engagement with the bot. But there is a very big difference between a bot designed to provide therapeutic support in a medical and supervised setting, and a general AI that presents itself as an AI therapist.

The Turing test famously refers to the development of a machine that can fool humans into believing they are communicating with another human. It is clear that the new generation of chatbots has long since passed that test. But in the field of mental health, that is not a good thing.

People seeking help for mental health issues are, by definition, vulnerable, which means that when things go wrong, they can have serious consequences. In 2023, the National Eating Disorders Association in the United States came under fire when it replaced its national helpline with a chatbot that ended up offering dangerous weight-loss advice to users as a result of an upgrade that saw the bot depart from scripted rules-based answers to generative AI.

Offering ersatz solutions that can exacerbate users’ problems is immoral and dangerous.

With the boom in generative AI chatbots since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2023, AI companies have promised that their tools can help address the needs of anxious and isolated consumers who need support but cannot afford professional psychotherapy. But often the chatbot operates by reflecting back users’ already difficult feelings. Offering ersatz solutions that can exacerbate users’ problems is immoral and dangerous.

The openly accessible “AI therapist” holds risks not only for those using it but also for the people around them. Two current lawsuits in the U.S. against one company providing AI chatbots as entertainment show how severe these risks can be. In one case, a teenage boy took his own life after tragic interaction with an AI character playing the role of confidante and girlfriend. In the other, an adolescent threatened his parents after engaging with an AI therapist alongside other characters. Among other arguments, the lawsuit cites deceptive and unfair practices as a result of the chatbots’ representation as licensed therapists.

As counsel for the claimants in those cases, Meetali Jain, put it: “If a person presented themselves as a psychotherapist without the appropriate credentials or licensure in real life, that person could be fined or criminally charged. Apparently, doing it digitally gives these companies a ‘get out of jail free’ card.”

Earlier this year, the American Psychological Association (APA) met with the Federal Trade Commission to highlight its concerns that AI chatbots posing as therapists can endanger the public. While recognizing that there may be a place for regulated specialist use of AI in a therapeutic context, the APA is extremely concerned about the deceptive nature of general entertainment chatbots posing as therapists to vulnerable populations.

In countries such as Canada, psychotherapy is a highly regulated sector, reflecting the seriousness of the impact therapists can have on their clients and the complexity of the role. And, even in the United Kingdom, where the sector is largely unregulated, those practising as therapists do not escape legal liability when things go wrong.

As AI chatbots are already being rolled out to support mental health services around the world, there is an urgent need for regulation and clear legal lines of liability around their use. While AI may provide vital tools to support stretched mental health services, it is vital that these tools are only used in a highly controlled and supervised manner, subject to the same levels of regulation as other medical and therapeutic devices. The risks of ungoverned use of AI by vulnerable people as a replacement for therapy, are, however, too great to ignore.

The manipulative potential of chatbots presenting as AI therapists is a threat also to the internationally protected right to freedom of thought, a right that governments are bound to protect. It is a rapidly expanding problem that requires urgent action.

In the United States, legislators in Utah have already proposed a bill for the regulation of mental health chatbots that use AI technology. Other jurisdictions will no doubt follow suit.

While the place for AI in formal mental health services continues to evolve, legislators could draw a clear line in the sand to ban AI platforms designed for entertainment from hosting characters that hold themselves out as mental health professionals.

There is no excuse for playing with users’ mental health and their right to be free from manipulation.