Last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that his government intends to release a COVID-19 notification app, which it claims will help Canadians protect themselves. There isn’t a lot of evidence or precedent to explain exactly how, so it’s worth reviewing the technology, the public health goals of COVID-19 notification applications and the predictable problems.

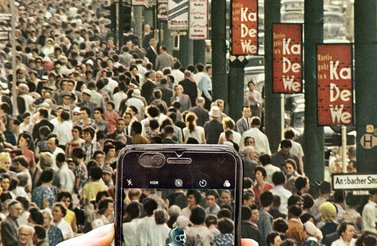

This application is a voluntary notification system, which works like this: smartphone users with compatible devices — an estimated 30 million in Canada (although there have been device compatibility problems with similar programs recently rolled out around the world) — may download the app, which uses Bluetooth to measure the phone’s proximity to others who have downloaded the app. If a person using the app tests positive for COVID-19, that person has the option to upload their verified test results to the app, which will then send a notification to anyone it determines the user has been close to during their infectious period. The notification app itself isn’t designed to recommend a treatment, but will recommend getting tested. The government sponsors are also working on including connections to social services that offer supports to people locking down on the basis of their COVID-19 risk. In its simplest form, the app is a voluntary technology that enables people to communicate potential risk to each other, shortening the time between exposure and testing.

Unfortunately, there aren’t any examples of notification apps (or contact-tracing apps) making much difference. And there are lots of examples of COVID-19 apps exacerbating tensions with very real consequences — whether by enflaming overzealous law enforcement, employers requiring app use as a precondition of returning to work, or by outing thousands of gay people through the contact tracing process. The heads of the contact-tracing programs in Singapore, South Korea and Iceland have said that contact-tracing applications have made little difference, and the Governments of Norway and Lithuania proactively suspended theirs, after ruling that they weren’t necessary or proportionate to achieving a legitimate purpose. At a fundamental level, the Canadian government releasing a COVID-19 notification application is more about signaling permission for others to use similar technologies than about deploying a functionally important technology.

There are three, foundational challenges to the notification app making a positive difference: first, we still don’t know enough about the virus to accurately model how it transmits, meaning that we don’t have the basic science we’d need to measure risk; second, the data we’re able to collect — location, temperature, proximity to other people — doesn’t reliably correlate to infection likelihood, because it doesn’t factor in major variables (such as wearing a mask or whether the app users are outside); and third, getting every person to use the same app all the time is impossible. A COVID-19 app deployment that achieved universal adoption, powered by government pressure and a public interest narrative, would be the most successful app in history. For context, despite billions of dollars in attempted platform-development and marketing, only 69 percent of Canadians use any kind of social media. In Australia, the only place to have hit its adoption target of 40 percent of smartphone users, there are still significant concerns about failure rates.

Encouragingly, the Canadian government has already moved the goalposts from the more ambitious (and dangerous) goal of app-based contact tracing to the more limited frame of optional “notification.” Notification is a somewhat subtle term for telling someone that they may have been exposed to the worst pandemic in modern history. The practice of giving people medical news and advice is, in most places, a highly regulated activity. And this, of course, is where it gets uncomfortable — the app doesn’t give you a diagnosis, it’s giving you a notification that your phone and the phone of a person who has tested positive for COVID-19 have been close to each other and, based on that, you should get tested. As a reminder, proximity is a weak indicator of COVID-19 transmission without a lot of additional details (mask usage, environmental context, ventilation). So, the app won’t violate the laws and professional standards meant to humanize medicine, by virtue of offering a probability instead of information or advice. The government app leaves it to the user to decide whether they lock down, seek a test or go on as though nothing happened at all.

Why then, is the prime minister announcing a weak signal indicator app that won’t trace COVID-19, or even give people a reliable risk indicator? Perhaps the decision is meant to provide the appearance that a government knows how to stop the pandemic. There is, after all, comfort in knowing that something is being done. More on that, perhaps, in another piece.

The Government of Canada plans to release the app in July, which means there’s plenty of time to focus on what matters and ensure that the technology supports sustaining public health amid COVID-19. In order to help the public to understand and trust the application, the government could productively consider a few, adjacent initiatives.

A necessity and proportionality analysis. The public would significantly benefit from a concrete description of the problems the app solves, the expected impact thresholds (graduated by public adoption rates) and why this is the best way to fulfill this need.

Policies prohibiting biomedical surveillance requirements and data reuse. Whether considering the Government of Canada’s app or something else, one of the main ways that potentially abusive practices become implemented at scale is through professional risk mitigation. Beyond any application, the Government of Canada’s release of an app should also act as a policy imperative to address the known second-order impacts of surveillance practices, including in insurance premiums, workforce eligibility and the inevitable judgments that support emergence from lockdown. Germany’s labour minister, amid an outbreak of 1,300 cases in a meat plant, is demanding civil liability and promising to shake up the industry. The Government of Canada will be far from the only stakeholder using technology to manage a dimension of its COVID-19 adaptation and response. It can still, however, set the bar.

An explanation of proximity notifications. It’s a lot to ask people to understand a notification based on experimental science and incomplete math. The government must ensure that the design of the application, as well as the information and resources available through the app, helps users to contextualize the information, de-escalate immediate feelings of concern and find locally accessible ways to seek care. It is also — and this is where structural equity is a factor — important to help users contextualize what happens if they receive a lot of notifications, or are unable to change their life in a way that reduces notifications.

Social consultation and safety nets around lockdown support. Choosing to lock down is the individual equivalent of the government locking down, and we need everyone to be able to do it. The Government of Canada has done considerable work to build a safety net for people during compelled lockdown. If notification and self-diagnosis are truly public goals, the app and the broader service infrastructure should create support structures for people credibly or reasonably choosing to lock down based on risk. These supports could be accessible through the app but would need to be implemented across a range of authorities.

Wind-down. If Canada’s experience after piloting the app is like Norway’s, or even South Korea’s, the government may consider winding this app down. The marginal costs of running or supporting the application are likely be small, but so too is the likely impact. Every intervention, especially in an emergency, should be able to measure its success (or failure) enough to know when to stop. Here, the government has made it clear that it doesn’t have any strong, or long-term, aspirations for this platform, so one way to build trust is to transparently publish the factors that will prove success or failure for this application, as well as a plan for winding down.

In many ways, Canada’s notification app benefitted from watching others launch, and is fortunate to be focusing on such manageable challenges around public trust in technology deployment. At the same time, why is the Government of Canada focusing on the rollout of experimental (at best) notification apps amid a historic pandemic and looming economic crisis?

App or not, the answer to that question is a notification that the public deserves.