Political advertising on social media has had a pivotal impact on democracy since the 2016 US presidential elections, through an amplified reach and the sowing of disinformation and division. In response to harms, major social media platforms restricted, or outright banned, political ads, only to lift these guardrails later.

In the coming election cycle, however, US voters will find themselves just as divided if not more, while contending with the rapid advances in technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and deepfakes, which have already been used in political ads and are bound to have a corrosive effect. We are therefore more vulnerable than ever, both from a technical and a societal perspective.

Although there are legitimate arguments against banning or restricting political ads, the harms of such ads still outweigh the benefits. Given the status quo — no ban on microtargeting, no regulation of data brokers, and a lack of comprehensive data privacy regulation — Congress needs to act now and ban these ads, at least during election cycles.

In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, Brad Parscale, then the digital strategist for Donald Trump’s campaign, boasted about the campaign’s exponential reach using Facebook, tweeting: “I bet we were 100x to 200x her [Hillary Clinton’s reach]. We had CPMs [costs per thousand people reached] that were pennies in some cases. This is why @TheRealDonaldTrump was a perfect candidate for FaceBook.”

The reason for the remarkable efficacy of the ads became clear in 2018 when whistle-blower Christopher Wylie revealed the Trump campaign’s relationship with Cambridge Analytica, a self-described “global election management agency.” The company improperly harvested data from more than 50 million Facebook profiles of US voters, which it used to build and target personalized political ads to influence and predict voter choices at the ballot box. That exploit was perhaps the first clue as to the immense power and transformative impact of political advertising on social media.

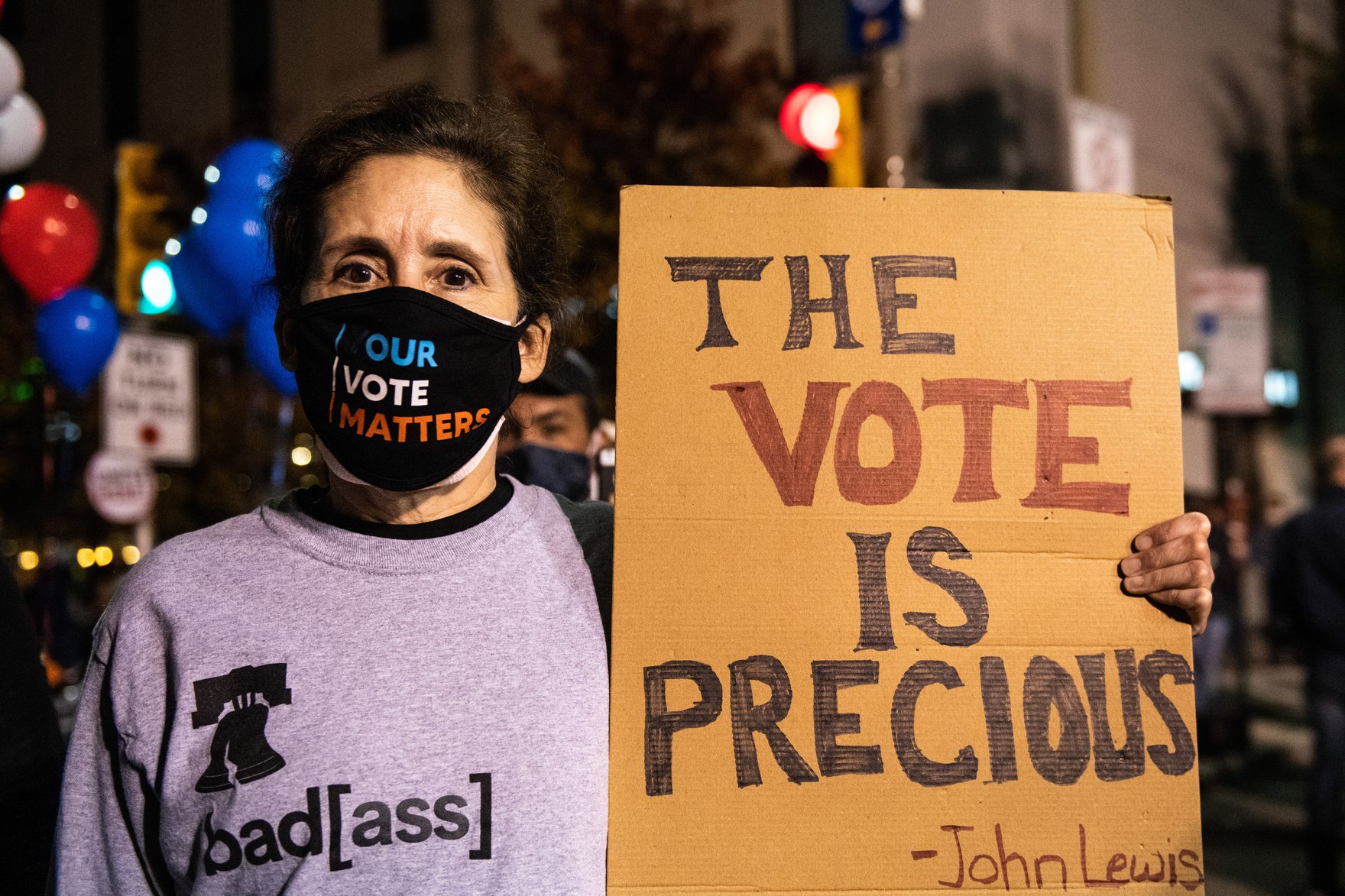

If there were still any doubt, consider the Trump campaign’s 2016 ads on social media intended to suppress the Black vote. The campaign selected 3.5 million voters, predominantly Black Americans, in 16 battleground states, for a category called “deterrence” — a category later described publicly by Trump’s chief data scientist as containing people who the campaign “hope don’t show up to vote.” This prompted Jamal Watkins, vice president of the NAACP, to call the ad “modern-day [voter] suppression.”

Deceptive ads seek to manipulate people’s thoughts and opinions. Freedom of thought, which also includes freedom from manipulation, is an essential component of the international human rights framework and, as described by Susie Alegre in a CIGI policy brief, is “connected to the corresponding right to ‘hold opinions without interference’ in article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.” Thus, manipulating internal thoughts, by any means, is a violation of the freedom of thought, a fundamental human right.

The truth is that effective digital political ads would not be possible without surveillance capitalism, the de facto business model of social media platforms. This advertising-centric model offers political campaigns an arsenal of precision tools for microtargeting their ads. Campaigns can microtarget messages to different niche audiences, sometimes with contradictory or inconsistent messages, while evading accountability for the sleight of hand.

Moreover, since social media platforms thrive on user engagement, more enticing clickbait content leads to lower ad costs. This relationship creates a perverse incentive to deploy ads laden with captivating visuals and emotionally charged content. Former Trump official Pascale’s reference to “CPMs” — the cost of reaching 1,000 people with a single ad — thus makes sense. In fact, he called Facebook’s ad policy a “gift.” Although Cambridge Analytica is now defunct, the lack of comprehensive privacy laws in the United States continues to enable massive data collection for microtargeting.

It’s worth noting that unlike the European Union, which has enacted a comprehensive data privacy law known as the General Data Protection Regulation, the United States has various federal and state laws that cover different aspects of data privacy. These laws can at best be described as a patchwork system covering niche use cases such health, financial data, or data related to small children. This leaves data collection unregulated in most states, where companies can collect, use and/or share user data without the knowledge or consent of the user.

Although Cambridge Analytica is now defunct, the lack of comprehensive privacy laws in the United States continues to enable massive data collection for microtargeting.

By 2020, having witnessed the consequences of political ads in the prior election cycle, tech platforms such as Facebook/Meta, Google, Twitter, Amazon, Spotify and TikTok took the exceptional step of banning political ads. Amazon’s ad policy prohibits political content such as “campaigns for or against a politician or a political party, or related to an election, or content related to political issues of public debate.”

Google and YouTube (owned by Google) have changed policies to require verification of veracity. Yet both Google and Amazon have faced criticism over ineffective enforcement. Facebook and Twitter lifted the bans in 2021 and 2023, respectively. TikTok continues to ban political ads.

Meanwhile, much has changed since 2020. Not only did the world witness the shocking events of January 6, 2021, but we have also observed the rapid advances in AI technologies, including deep learning algorithms used to create deepfake audios and videos, which make navigating a polluted information ecosystem that much harder.

There is currently no ban on using deepfakes in political ads, as the Federal Communications Commission is deadlocked on the decision. Imagine if the 2005 Access Hollywood tape that The Washington Post published before the 2016 election had instead been released today. How much plausible deniability would these tech advancements have afforded Trump?

Speaking of lies and legality, it may surprise some to know that in contrast to commercial advertisers, political advertisers can not only bend the truth but also outright lie. Political ads, for better or for worse, are considered free speech and protected under the US First Amendment. Social media companies can, however, ban political ads under their terms of use; nonetheless, they face two challenges in doing so: transparency and fact-checking.

In 2018, Google introduced a searchable database of US political ads, aimed at enhancing transparency across Google, YouTube and affiliated platforms.

Facebook launched the Ad Library in 2018. But these efforts have also been met with criticism.

Fact-checking political ads is not possible at scale; imagine the number of political campaigns in the United States and now multiply that for every country across the globe. Even if that were possible, there are still judgment calls to be made, and social media companies lack the expertise necessary. Outsourcing fact-checking to reputable third-party sources is one option, but it still carries the risk of perceived bias and disputes. For example, is a statement from a candidate hyperbole or a lie? Is a particular statistic cited in a way to mislead or not? Any judgment is bound to generate criticism from one party or another.

Is banning political ads the perfect solution? By no means. There are still workarounds for the unscrupulous. For example, “influencers” can be paid to spread the message. A study from Duke University’s Center on Science and Technology Policy expressed legitimate concern that banning political ads may hurt the upstart candidates more than the incumbents. Lastly, it’s difficult to define what constitutes a political ad. Ideally, we would deal with the fundamental issues, such as the harms of surveillance capitalism, protecting data privacy and banning microtargeting. But given the pace of legislation and the looming election, those are lofty aspirations versus actionable options.

As with anything in the real world, the answer is neither black nor white. The question then becomes: “Do the benefits of political ads on social media outweigh the harms?” In this case, the answer is a clear no.