Tackling Cyber-enabled Crime Will Require Public-Private Leadership

icture an ordinary town. On one side of the community there are flourishing businesses and beautiful homes, a lush park, and a school. But they are cordoned off as a gated community with their own private security.

The other side of the wall is completely different. Levels of crime and despair are high. Drugs and weapons are widely available. The sex trade is rampant, including trafficked children. And violence stemming from hatred is a constant fear. Police presence beyond the occasional drive-by is non-existent.

This may sound like an opening scene from a futuristic dystopian film. However, if we look to areas of the internet today, the analogue analogy isn’t far-fetched relative to our current digital reality.

As a result of the rapid pace of technological innovation and the decisions embedded in the software that make up social networks, online marketplaces and other parts of the internet and digital devices, existing laws are often no longer enforceable and the principles that form the bedrock of the rule of law are eroding. This, coupled with the limited legal and technological tools available to law enforcement in the digital age, places ordinary citizens — in particular vulnerable populations such as children, seniors and individuals suffering from mental health challenges — at risk.

Traditional crimes such as burglary and motor vehicle theft are generally down in the liberal-democratic world. In Canada, Criminal Code violations are down significantly. In 2006, there were 2.4 million offences compared to 1.9 million in 2016.1 Breaking and entering dropped from 250,000 occurrences to 160,000; motor vehicle theft decreased from 159,000 to 79,000 over that period.2

These crimes are by no means new. What ties their contemporary growth together is the ease by which they can be committed with relative impunity in the digital age.

These statistics would lead us to believe we’re safer. But looking at the crime statistics through another lens paints a much different picture. Crimes such as the sexual exploitation of children, human trafficking, fraud, and terrorism and mass casualty incidents are all up. For example, Statistics Canada reported in 2016 that child sexual exploitation increased for eight years in a row at a rate of 233 percent (Harris 2017).

These crimes are by no means new. What ties their contemporary growth together is the ease by which they can be committed with relative impunity in the digital age. This isn’t to say there aren’t laws against the sexual exploitation of children, fraud or other crimes enabled by digital connectivity. Nor is it to say police agencies don’t have personnel and tools to investigate digitally enabled crimes. In fact, most agencies of scale in advanced industrialized countries have what are known as digital forensics labs to investigate cyber-enabled crimes by collecting digital devices with critical evidence and examining them. This is costly and deeply technical, and is reserved for major crimes such as homicides and organized crime. The general trend is that these investigations are becoming even more complex due to emerging technological trends and the lack of either a technical or public policy response. This has been further exacerbated by a growing chasm between police agencies and emerging technology companies on their respective societal roles.

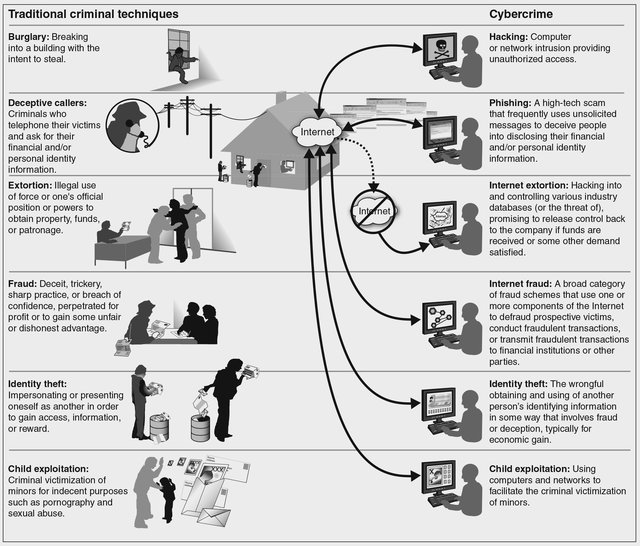

Figure 1: Comparison between Traditional Criminal Techniques and Cybercrime

Technologies Enabling Crime in the Digital Age

Cloud Computing

Cloud computing is transforming the internet and its application — in large part for the better. Simply put, cloud computing off-loads the cumbersome and expensive digital infrastructure required to run applications, store data and enable advanced analytics to third parties, including some of the largest corporations in the world, such as Amazon and Microsoft. This has significantly reduced the operational costs of starting a digitally enabled or wholly online business given the cost and technical advantages.

While the economic advantages of the cloud are clear, the downsides to the criminal justice system are lesser known. Prior to the advent of cloud computing, investigators could petition courts, through warrants, to confiscate digital devices such as computers and smartphones where it was suspected they contain critical evidence regarding a case. Using their technical background and software tools, they could recover critical evidence that resided on the local device, analyze it and report on it to the broader justice sector.

Police agencies still have the ability to petition the court. However, cloud adoption is making the gathering of digital evidence difficult. Many data centres that store cloud-based data are located in foreign jurisdictions, often where the company can get economies of scale, better tax treatment, access to technical talent and favourable data policies. This adds a layer of complexity as law enforcement agencies must work in concert with their national governments and their foreign partners to request such data from private vendors. In the case of most liberal democracies, Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) exist to help streamline these judicially authorized requests for evidence from a vendor in another country.

Many data centres that store cloud-based data are located in foreign jurisdictions, often where the company can get economies of scale, better tax treatment, access to technical talent and favourable data policies.

This approach is not a perfect solution, as the requests must also comply with domestic laws, including those that pertain to data privacy. For example, in surrendering data about a customer, a private vendor could not turn over data about another individual. Often such data isn’t housed in a neat manner, placing the vendor at risk of breaking domestic law if they were to comply with the MLAT process. The process is opaque in cases where a treaty does not exist with a country where critical data for a law enforcement investigation resides.

Even when critical data regarding investigations can be tracked down to a cloud service provider and an MLAT exists between the countries in question, the process is quite time consuming and costly, and places investigations at risk. For these reasons, this process is often reserved for major crimes.

This issue reached a tipping point in the United States. In 2018, Congress passed legislation titled the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act. Principally, the act asserts that US technology companies must provide data about US citizens on any server they own or operate when requested by a legitimate court order. The CLOUD Act was informed heavily by a 2013 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)-organized crime investigation, which moved slowly through the courts, over access to data about a suspect who had been protected by critical evidence on a Microsoft server in Ireland. This case made its way into the queue at the Supreme Court before Congress acted. Microsoft welcomed a legislative response to this gap in public policy given the risk posed to the reputation of its emerging cloud and cloud-enabled business lines (Cheng 2018).

Encryption

While cloud computing is transforming technology in general, for law enforcement there is still often critical evidence on smartphones, computers and now some Internet of Things devices, including text messages, pictures and videos, as well as behavioural data points such as geolocation information or time stamps. Much of the efforts of digital forensics labs in police agencies are focused on this area.

However, in recent years, there has been a technological transformation to device security, specifically around smartphones, that has hindered law enforcement investigations. All major smartphone manufacturers now include encryption security on the physical device as a default setting and link it to a passcode or other form of unlocking, such as fingerprint or facial recognition software. If too many attempts to gain access occur, the device is wiped of all data on the physical drive. This has led to fewer stolen smartphones but has had significant implications for other law enforcement investigations.

A 2016 terrorism-related case in San Bernardino, California, is the most prominent instance where smartphone encryption has rendered digital forensics futile. The FBI stated it could not access critical evidence on the suspect’s device and petitioned the court to compel the device manufacturer, Apple, to assist in unlocking the device. Apple stated that it did not have the technical capability to comply with such an order at that time and would not re-engineer its encryption to allow for that ability in the future.3

The issue goes well beyond a single terrorism case. For example, in 2016, the New York County District Attorney (DA), Cyrus Vance, stated there are more than 400 iPhones related to serious crimes that the DA office could not access even with a court order. Other jurisdictions report relatively similar outcomes (Tung 2016).

Vance also called on the US government to introduce legislation that would address this issue. Laws proposed included ones compelling device manufacturers to maintain encryption keys or suspects to unlock their devices should a court order exist. However, a constitutional challenge could arise from the latter, under the US Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, which states that no American shall be compelled in a criminal case to be a witness against themselves. Such legislation has been debated in the United States and the United Kingdom, but no device encryption laws have been enacted to date.

Laws proposed included ones compelling device manufacturers to maintain encryption keys or suspects to unlock their devices should a court order exist.

In the absence of enabling public policy, law enforcement has utilized technologies that find vulnerabilities in smartphone encryption to unlock devices and perform digital forensics. While this approach is successful in some cases, it is a costly and imperfect science, given that the device manufacturers regularly update software.

Application encryption is another challenge. Commonly used messaging, social media, marketplace and business productivity “apps” employ encryption technology to provide security for users.

This is a lesser challenge for digital forensics professionals, relative to device encryption, as decryption keys are required for the intended audience to consume the data. They can be utilized in law enforcement investigations as well. However, certain applications are architected to maintain user anonymity throughout the life cycle of data creation and storage. Further, some app developers change the way they store critical data on a regular basis, through their product updates, which can seize the abilities of digital forensics tools and professionals. Criminals, including child sexual predators, terrorists, fraudsters and those involved in organized crime, who understand such technologies can and have leveraged them.

In late 2018, Australia became the first jurisdiction to legislate against application encryption. The law enables Australian police agencies to compel companies to create a technical function to give them access to messages related to a specific user via the technology provider without the knowledge of the user (BBC News 2018).

The Deep and Dark Web

Sophisticated criminals have also benefited from the “deep” and “dark” Web. The origins of this cavernous, unindexed area of the common internet is often debated. The US Naval Research Laboratory is attributed as the creator of technology behind “The Onion Router,” shortened to Tor, which protects user identity by routing traditional location services and Internet Protocols (IPs) through a number of countries. The US government’s intended use was to provide a mechanism for dissidents in repressive regimes to be able to communicate without tipping off authorities (McCormick 2013).

Today, the deep and dark Web has become a safe haven for criminal enterprise. A 2016 study by King’s College London researchers found that of 2,723 sites they were able to analyze over the deep Web, 1,547 hosted illicit content including drugs, child sexual exploitation images and videos (often referred to as child pornography), weapons and money laundering (Moore and Rid 2016).

While investigating cases on the deep Web can be challenging for law enforcement due to the anonymity it provides users, some technological advancements have been made. Thorn, a US-based, global non-governmental organization, has developed technologies to assist law enforcement agencies in identifying victims of child sexual exploitation and human trafficking through images and videos found on the dark Web and open internet, leading to some successful, high-profile criminal prosecutions. However, the deep and dark Web remains a relatively safe haven for the criminal enterprise due to the anonymity it provides users.

Cryptocurrencies

Following the exchange of money in a criminal investigation has long been a tactic for police investigations; however, the advent of cryptocurrencies has hindered this approach. The key distinguishing feature of cryptocurrencies relative to traditional forms of currency is that they are a wholly digital asset class leveraging cryptography to secure transactions, control the creation of additional units and verify transactions. The other differentiator is that they are a decentralized currency, without a central bank or clearing house for transactions, regardless of the size of exchange. The latter feature has posed a great challenge for law enforcement investigators as they must find leads other than lawful tips from the banking sector or regulators to identify currency exchanges.

The most common form of cryptocurrency is Bitcoin. Given its popularity and prevalence in criminal investigations, larger law enforcement and national security agencies have developed some techniques to recover Bitcoin-related evidence from physical devices, known as “Bitcoin wallets.”

While those techniques have worked in some cases, it is an expensive and highly technical investigative area, limited to major crime investigations by some of the world’s largest police agencies. It also doesn’t address the fact that there are now over 1,500 known cryptocurrencies, some of which are layering other forms of security and anonymity of its users, nullifying investigative techniques.

The technical underpinning of cryptocurrencies, known as “blockchain,” is also gaining adoption in other areas of computing. This will pose an even more complex challenge for digital forensics labs in the future, especially when blockchain is coupled with cloud computing.

The Way Forward: Understanding the Magnitude of the Challenge and Bridging Public and Private

The connectivity provided by the internet and digital devices is accelerating the volume and variety of products and services available to consumers at an unprecedented velocity. This has brought great progress in terms of social connectivity and commercial opportunities.

These very technologies are challenging police agencies and governments in their societal role to keep citizens secure and upholding the rule of law. But the magnitude of the impact these technologies are having on the fundamental pillars of liberal-democratic societies, specifically in the criminal justice sector, is less known.

A key part of the response to this challenge is better data. Crime statistics in most democracies are woefully inadequate. They often don’t capture how digital technologies enable crime or categorize crimes based on pre-digital-revolution categories. This data is integral to police agencies as their funding is often tied to such crime statistics.

The magnitude of the impact these technologies are having on the fundamental pillars of liberal-democratic societies, specifically in the criminal justice sector, is less known.

One area that has seen some innovation on gathering statistics is child sexual exploitation online. The Canadian Centre for Child Protection (CP3), a non-governmental organization, which operates Cybertip.ca, has developed an online portal to capture citizen reporting of such incidents. The portal receives more than 4,000 reports of online child sexual abuse images and videos each month (CP3 2017). Understanding the specific nature of this challenge with data has allowed the Government of Canada and provinces to invest strategically. For example, with additional resources, CP3 has developed an automated technology to notify hosts of illicit content to take it down within the confines of existing laws. While such data has not led to legislative change in Canada, greater public awareness could lead to political action as it permeates through Canadian society.

That being said, legislating for or against specific technologies may not necessarily have the impacts required to wholly reverse the current trend in digitally enabled crime. Technological innovation happens at a much more rapid pace than legislative change in most democracies. Further, most internet-enabled technologies can be utilized across jurisdictions with ease, which often renders domestic laws futile and international co-operation remains a slow and costly process. Legislation in this area should remain based on principles as opposed to prescriptive in terms of technological specifications, such as the removal of encryption from smartphones.

The greatest innovation required in addressing the growth in digitally enabled crimes is the relationship and feedback loops between the public and private sector — specifically law enforcement agencies and technology companies.

Technology companies have latched on to recent public opinion that law enforcement and national security agencies can’t be trusted to have access to private citizens’ digital communications. They, in concert with privacy advocates, have banked on this sentiment to justify their development, which has rendered court orders futile and placed the rule of law in a precarious position. Conversely, law enforcement agencies have rarely highlighted the day-to-day challenges they face when it comes to cyber-enabled crimes and the growing complexity they pose. Without that level of transparency, it is difficult for citizens to make informed decisions as consumers and citizens.

This is not a sustainable approach. It’s important to consider that we’re still early in the digital age. As more citizens are affected or learn of cyber-enabled crimes, public opinion will inevitably shift. Both government and technology companies will have to rethink their positions.

Fundamentally, liberal-democratic societies cede reasonable amounts of individual civil liberties in exchange for societal security. There isn’t a static balance. It’s highly dependent on the current state of affairs. Without meaningful and regular dialogue between all vested interests, the current chasm will only grow. These parties will have to work with lawmakers around the world to reshape relevant legislation, in a principle-based fashion.

Works Cited

BBC News. 2018. “Australia data encryption laws explained.” BBC News, December 7. www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-46463029.

Cheng, Ron. 2018. “Seizing Data Overseas from Foreign Internet Companies under the CLOUD Act.” Forbes, May 29. www.forbes.com/sites/roncheng/2018/05/29/seizing-data-overseas-from-foreign-internet-companies-under-the-cloud-act/#6b1bb61f16c0.

CP3. 2017. “Statement: New Statistics Canada Report Reflects Alarming Reality of Sexual Abuse of Children.” News Release, July 26. https://protectchildren.ca/en/press-and-media/news-releases/2017/statcan_report_child_sexual_abuse.

Harris, Kathleen. 2017. “Reports of child pornography, sexual crimes against minors on the rise.” CBC News, July 24. www.cbc.ca/news/politics/sexual-offences-children-increase-statscan-1.4218870.

McCormick, Ty. 2013. “The Darknet: A Short History.” Foreign Policy, December 9. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/12/09/the-darknet-a-short-history/.

Moore, Daniel and Thomas Rid. 2016. "Cryptopolitik and the Darknet." Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 58 (1): 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2016.1142085.

Tung, Liam. 2016. “New York DA vs Apple encryption: ‘We need new federal law to unlock 400 seized iPhones.’” ZDNet, November 18. www.zdnet.com/article/new-york-da-vs-apple-encryption-we-need-new-federal-law-to-unlock-400-seized-iphones/.

US Government Accountability Office. 2007. Cybercrime: Public and Private Entities Face Challenges in Addressing Cyber Threats. June. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office. www.gao.gov/new.items/d07705.pdf.

The opinions expressed in this article/multimedia are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIGI or its Board of Directors.