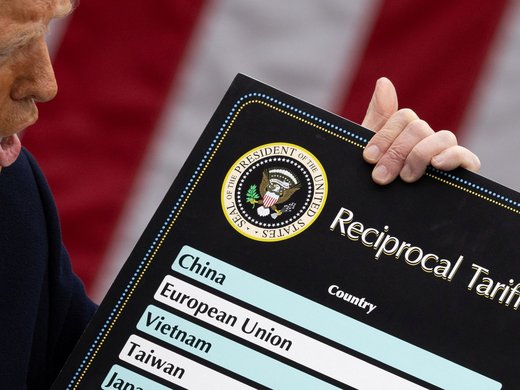

As the trade war between the world’s two largest economies further escalates, with US$16 billion in tariffs and counter-tariffs between the United States and China coming into effect, a deep-seated conflict is emerging. Behind the United States’ attack on China’s forced technology transfer policy, intellectual property theft and Made in China 2025 strategic plan, and behind the tit-for-tat tariffs, there lies a fundamental fault line of the trade war: the clash between the Chinese state-dominated economic model and the US-led free-market economy system.

Judging by his tariffs on allies and his embrace of a dictator, it appears that US President Donald Trump doesn’t typically care about ideological or political views as long as they align with his “America first” policy. However, the attack on Made in China 2025, a plan to develop China’s high-tech industries, has seemingly, intentionally or not, turned into an assault on the core of China’s political and economic system. The Chinese model is characterised by its government-led and -supported industrial growth and innovation that includes elements such as state-owned enterprises in key sectors, government-guided industrial policy and cheap credit from banks.

This challenge to Beijing’s economic model gained bipartisan support from elite groups within Washington’s China-policymaking community. It seems they are no longer under the illusion that China can be incorporated into the US’ free-market capitalism, and they think their China policy over the past two decades has failed.

Since China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001, and despite its further market reforms and booming private sector, China has retained state capitalism and even reinforced its coercive regime in the era of globalisation, thus developing into the world’s second-largest economy. The nation’s strategic transition and the growing resentment in US China-policy circles underpin the consensus on Trump’s policy: that China is succeeding at America’s expense.

The rationale for Trump’s challenge to the Chinese model and push for Chinese integration into the rule-based free-market economic system is similar to his predecessor Barack Obama’s. The difference is in the approach. Whereas Obama adopted the elaborately structured and face-saving approach of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Trump used a crude, downright old-fashioned weapon: tariffs.

But Trump’s dogged attack has hit a nerve in China. Under the growing external pressure and the internal economic downturn exacerbated by the trade war, the Chinese leadership and elite are reviewing whether they have underestimated Trump’s determination to overhaul US policy on China. In a popular view in China, existing relationships are based on the belief that close trade and investment relations are the ballast of US-China ties, and until now, never has any United States president, from Richard Nixon to Obama, challenged that.

How can the trade war end? As the openness to discussion indicates, there is a sufficient overlap between Trump’s wants and China’s willingness to deepen its economic reform and further open its economy. Although the countries’ close economic ties have been overshadowed by the trade war, they still constitute the foundation of the US-China relationship. Given this reality, compromise is possible, even if conflict between the US-led free-market system and the Chinese model is inevitable.

On China’s part, there are ways it can respond to America’s concerns over government subsidies to its industries, such as providing preferential loans instead of direct subsidies. Institutional arrangements, such as a new US-China intellectual property rights pact, could help better protect US intellectual property, as well as key technologies in China. They could also restart their stalled bilateral investment treaty talks and make room for these adjustments.

The Chinese model could come across as less threatening to the US-led economic system if the Chinese could reverse their current approach. Beijing could tone down the bragging about its overstated economic and technological capability.

Instead of focusing on state economic growth, China should shift its attention to improving income, welfare and education investment for its huge working-class and migrant labour population. It could also upgrade poor infrastructure – medical care, education, internet, heating, hygiene, water – in underdeveloped villages and towns.

Redirecting the focus of the Chinese model would show the world that China is still a developing country.

This article first appeared in South China Morning Post.